II.2. Paradigms in Strategic Communication

Franzisca Weder

After some clarifications around the two paradigms of communication, we want to focus on organizations and their stakeholders and how (much) they are communicatively ‘linked’. So before we look at the paradigms and how they influenced existing definitions and conceptualizations of strategic communication, we need a basic understanding of organizations, stakeholders and audiences.

Watch Organisations and organisational communication (YouTube, 18m36s) for an introduction into the key terminology and definitions.

Let’s summarize:

- an organization consists of a group of people;

- … who work together to achieve a common purpose;

- an organization is bigger than the individuals and groups that comprise it, but smaller than the society that gives it its context and environment.

Photo by Alex Kotliarskyi on Unsplash

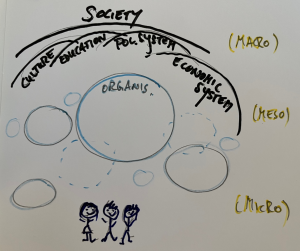

Organizations can be rather loosely coupled, for example a network, virtual team or association, or hierarchical with a strong vertical organizational and thus management structure, like a big company. Organizations are situated as structural complex between individuals (who are embedded in various organizational structures, like University, sports club, political party etc.) and the society and its subsystems (i.e. the education system, the economic or the political system). See the graphic below:

Graphic: “Organisations” by Franzisca Weder

Organizations interact with other organizations (i.e. their competitors, clients or suppliers), they are not only embedded in the society but closely related to some key groups who have an interest in the organization and its services and products and by the same time are affected by the organizations decision making. They are called ‘stakeholders’. The earliest definition of a ‘stakeholder’ is credited to a memo produced in 1963 by the Stanford Research Institute, defining stakeholder as those groups without whose support the organization would cease to exist. A ‘stake’ means an interest in an organization, for which a justified and normative demand can be made (Reed, 1999); thus the “stakeholder is any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievement of the organization’s objectives.” (Freeman 1984, p. 46).

Watch Organisations and stakeholders (YouTube, 30m25s) for a better understanding of organizations and their stakeholder from a strategic communication perspective.

Since the 1980s, stakeholder theory has developed to explore all groups who potentially affect an organisation, the main reason for that is that if an organisation neglects a stakeholder group, the group has the ability to have a negative impact on the organisation. Stakeholders provide resources, which are important to organizational success e.g. capital, workforce, ‘licence to operate’, social acceptance. Their well-being is intertwined with the fate of the organization e.g. employment, environmental conditions, products and they have sufficient influence to impact organizational performance e.g. mobilising of social forces, restraining resources. Because it is impossible that all stakeholders will have the same interests in and demands on the organization, stakeholder management is about managing potentially conflicting interests. This means we need to be strategic and planned when dealing with stakeholders. For a deep dive into stakeholder theory, read About the Stakeholder Theory.

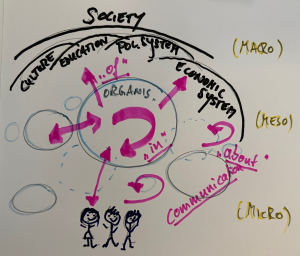

Why is this important for our definition of strategic communication? Because the organization-stakeholder relationship is often stimulated by, facilitated and operationalized through communication. As mentioned in the previous chapter, communication happens on an individual level, but also on an organizational level, which includes interpersonal communication situations and ‘organisational’ communication as much as planned internal and external communication endeavors to inform and engage stakeholders (see following graph).

Graphic: Interpersonal and organisation organisation by Franzisca Weder

In the literature that describes strategic communication – within and beyond organizations – again, the pragmatic, functionalist or ‘realistic’ perspective is much more established. From the beginning, pragmatism has influenced strategic communication scholarship, increasingly articulated over the past decades. As described in chapter II.1, pragmatism is even seen as central communication-theoretical perspective (Craig, 2007; Russill, 2008), especially in strategic communication, management communication, political and corporate communication. Here, communication is approached with an idea of control and a strong impact focus, media are perceived as carrying and disseminating (key) messages.

Strategic communication is the umbrella term that embraces different communication directions, levels and concepts. Therefore, strategic communication is often described as the purposeful use of communication by an organization to fulfill its mission (Hallahaan, 2007, p. 3; Holtzhausen & Zerfass, 2015). This goes back to the pragmatic approach to communication and a functionality or instrumental understanding of communication. How much it differs from a rather constructivist lens on planned or ‘managed’ communication can be seen in the following:

Strategic communication (structural perspective)

- the purposeful use of communication by an organization to fulfill its mission(Hallahaan, 2007, p. 3; Holtzhausen & Zerfass, 2015)

- understanding “how a certain set of audience attitudes, behaviors, or perceptions will support those objectives” is what makes communication strategic (Paul, 2011, p. 5).

Communication management (process related, constitutive perspective)

- constitutive flows of communication (McPhee & Zaug, 1995, Putnam & Nicotera, 2007; Schoeneborn et al., 2016)

- Questions: narratives, discourses, interaction, interrelatedness, power, negotiation processes

We can see that complementary to the concept of purposeful use of communication by organisations to fulfill their mission and communication as supporting objectives and a certain goal, a constructivist and rather critical paradigm has gained more advocates over the years. Instead of a one-directional perspective on communication and focus on media as communication structure and facilitator for transmitting messages, communication from a ‘new paradigmatic’ perspective is perceived as process, as ‘flowing’, as following certain storylines or narratives, and is characterized as interactive, lacking central control or regulation, as being a sense- and meaning making process at the same time. Part of this thinking is that change often happens through communication within and beyond organizations. With this perspective (use your red glasses), communication can change behavior, patterns of behavior, beliefs and culture, can establish new rules and routines – more or less radically. Then, communication is a diversity of phenomena and experiences (McQuail, 2013), beliefs, states of mind, climates of opinion or attitudes, social and revolutionary movements with their own dynamic, as well as various patterns of interaction and social life, of debate, problematization and conversation. All these conversations are impossible to capture within the original, pragmatic mass communication paradigm; they are not originated and directed by a sender from a specific source; they need subjective interpretation. If you’re interested in a deep dive into a more constructivist understanding of organizational communication, read The Communicative Constitution of Organization, Organizing, and Organizationality

These critical perspectives have influenced media and communication studies and their subdisciplines; they are even sneaking into research areas that are dominated by and even originate in a pragmatic, instrumental understanding of communication, like organisational communication, Public Relations as well as related areas of communication management or marketing. Critical or social constructivist approaches do not limit strategic communication to external on the one hand and internal communication on the other hand. They rather focus on communication for organisations, encapsulating every conversation within an organisation and between an organisation and its stakeholders. The idea is that a certain meaning or organisational culture and even reputation is co-created and constructed in every conversation, in every quick chat in the staff kitchen.

Let’s have a play with your glasses and look at an example of strategic communication:

Exercise

Visit What sustainability means at Shell and do the following exercise:

Use your cut out blue glasses and look at sustainability reporting of Shell, for example, at their press releases or their webpage. You might discover their vision of sustainability, communicated to their stakeholders (one directional, transmissive). The functionality here is to show that Shell aims for a contribution to the Global Sustainability Goals (see chapter 1).

“In addition, we may also contribute to the other SDGs, for example through the policies and operating practices we adopt, the partnerships and collaborations we work in and the social investments we make” (Shell, 2020).

From a constructive, sense making perspective, this sentence seems to be a “hollow notion” (Weder et al., 2019). To explore ideas and possible unique narratives constructed and offered to the website visitor, we can find the following under the headline “A fair and just transition”:

“We are working in various countries to explore viable pathways towards a prosperous, low-carbon future tailored to individual country context” (Shell, 2020).

Here, Shell follows the meta-narrative of sustainable development being a process of transition. However, this can be rather labelled as aspirational talk (Christiensen et al., 2017), there is no further disclosure of their own interpretation and negation processes about the meaning. The strategy and the tactics that are applied for this “exploration”.

Before we further explore existing CSR and sustainability communication in part III with our glasses, we need to dig deeper and gain a better understanding of the two paradigms sketched out and their applications in CSR and sustainability communication so far.