I.2. Sustainability, CSR, ESG and more: terminological clean up

Franzisca Weder and Marte Eriksen

The lady…

I stopped the lady on the bike; I made her to put her Birkenstock-shod foot on the asphalt, glowing from the heat. It was one of those days in the tropical south of our planet, one of those days where the city we live in glitters brightly in the sun, the hot air shimmers and the humidity reaches into the marrow of our bones. She looked at me with her brown eyes, tiny little laugh wrinkles amplified her bright smile. I asked her: You look like someone who can finally tell me what sustainability is. She looks at her bike, wiped tiny beads of sweat of her temples and said – well, it’s a matter of how I use my own resources to climb up this hill – will I use all my power, then I will not be able to climb the next hill; it’s a bit of an interplay between me, my bike and my power and the road and the hills. Sustainability needs a holistic process of thinking, it also implies the consideration of how much my actions impact other people and the environment.

A bit more sophisticated, sustainability is a principle that (re)connects people with the planet following the principle of sufficiency (which by the way has been included for the first time in the IPCC report) – but not without including the aspect of efficiency, the aspect of resources that can be used and thus an economic dimension (see the following definition).

Sustainability

the ability to be maintained at a certain rate or level.

Or even more precise: avoidance of the depletion of natural resources in order to maintain an ecological balance.

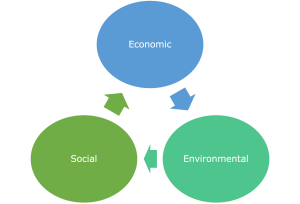

Sustainability is often described as a idea that is used to look at social, environmental or economic issues or behavior, or to explore the intersections of those three dimensions, for example challenges at the intersection of the social and economic dimension around social equity and equality or of economic and environmental interests and the question of viability. This goes back to the so called ‘triple bottom line’ or there dimensional model of sustainability, that captures the there domains where sustainable development should be realized guided by sustainability a principle:

Figure: “Three dimensions” by Franzisca Weder 2023

Sustainability, thus, is first of all a term that describes the “ideal” or balance between what is possible and what is reasonable, between what we need to exist considering future generations and their needs (UN, 2020; Weder et al., 2021). But sustainability goes further than the description of a certain status quo of ‘balance’, or resource security. Sustainability has also developed into a guiding principle, a principle of action that stimulates organizations of all kind and individuals to become better stewards of the environment, the society as a whole and the future. It inspires action and communication about how to combat specifically climate change and imbalances – in all dimensions. The process of getting there is described as sustainable development:

Sustainable development

development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

Sustainable development includes all processes and structures that follow the principle of sustainability – or, the other way around, sustainability is the principle that guides actions that are part of a social transformation process that is labeled as sustainable development.

There is a set of goals, developed by the United Nations, which emerged from the first written Report dealing with the principle of growth – so called Brundlandt report (Our Common Future). The 17 goals are colorful and cover the whole breadth of sustainability issues; it works as a framework for political and organizational action.

Image: “Sustainable development goals”, United Nations, Own work using: File:Sustainable Development Goals.png and PDF infographic from un.org, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

While sustainability is often described from an environmental perspective and thus used as synonym for “green” or resource-orientation, the SDGs represent not only the intersections and dependencies of the three dimensions (ecological, social and environmental); much more, they show that there is actually not one area of the society that is not included in the big transformation, called sustainable development.

The lady…

Considering that sustainable development connects the past with the future and gives us an idea of how the future not only can look like but needs to look like, we need to talk about responsibility first. Responsibility is – generally spoken – a relational term. Responsibility is allocated and taken. Therefore, responsibility relates one organization to another (or to their stakeholder or audiences), two individuals to each other (mother – child) or even an individual to an organization (researcher – University). This thinking goes back to the German philosopher Imanuel Kant and his idea of ‘imputation’ in the sense of an attribution or assignment of responsibility (1968) from one individual to another or one person to a broader structural complex (i.e., group, team, organization, or ‘the society’). However, responsibility is never a moment of security or cognitive certainty, instead it comes with the ‘removal of grounds’, and the withdrawal of rules or knowledge on which we rely to make our decisions (think about a political crisis, stakeholder expectations that no one was considering, or the United Nations coming along with sustainable development goals and challenging business of all kind and size etc.). While responsibility-relationships are stable, the roles of responsibility are rather fluid (someone is in charge – but it is not necessarily the manager him or herself).

The lady…

Moral agency can be interpreted as ‘normative competence’ (Wallace, 1994); this involves the ability to grasp and apply moral reasoning, and to govern one’s behavior by the light of such reason. This means, that certain roles come along with a certain responsibility – which we can call role related responsibility: “responsible agents are not those agents whose actions are un-caused, but rather those agents who possess certain competences or capacities” (Vincent et al., 2011: p. 1f.). This would imply that the competences and functions of allocating and taking responsibility are clear; the more they are institutionalized, the easier they can be realized through interactions and for example particular communicative acts. A business manager has agency, because there are certain responsibilities institutionalized and therefore connected to his leadership role; in his role he can take moral agency in being a role model and lead the organization ethically.

Case study

Photo: “Josef Zotter” by Winfried Weithofer is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

This is Josef Zotter, Chocolatier, Eco-farmer and “out-of-the-box-thinker”. His chocolate company is one of the outstanding examples of sustainable leadership and business in Austria and Europe. His holistic concept goes back to his very personal decision to use only eco- and fair-traded resources for his chocolate products; he even goes further:

– solar power & geothermal energy: the whole production of Zotter chocolate relies on renewable energy; the peal of the chocolate beans is not thrown away; they are used in a steam power plant to generate heat and are used to fertilize the environmental surroundings of the factory.

– employees: every employee gets a free organic lunch with food from the own garden/farm, aligned to the factory.

– packaging & waste: no glas and no plastic is used in the fabric and for the packaging of the chocolate, instead, they rely on Biomat/renewable commons (Naturabiomat) and eco-friendly paper & printing colors

– e-mobility: all cars of the Zotter-fleet are e-cars, as well, visitors can re-fuel their e-vehicles at the local “power-bank”.

– EMAS certificate, Trigos-price receiver, partner of the Austrian climate consortium: Zotter is engaged in national and international sustainability networks and receiver of various eco-labels/certificates and prizes.

– in his private life, Josef Zotter lives self-sufficient, relying on his garden and network of farmers.

The case study shows a great examples of individual agency, moral agency to be more specific. However, without any structure or framework, individual ethics and ethical leadership can hardly take place.

In other words, the less structure or legal frameworks exist which allocate and define the agency for taking and allocating responsibility, the less attention is given to the constructive potential of communication when it comes to a moral framework, a common understanding and realization of role-related moral agency. Thus, even the broad discussion about virtue ethics or individual ethics in the area of business ethics (further read: Whetstone, 2001, Moore, 2005) is only one side of the coin.

Responsibility – especially from a sustainability perspective – is not only focused on the near field of a person. Hans Jonas, one of the most famous philosophers talking about responsibility, pointed out that it is important to think further – and include the responsibility towards our ancestors as well as future generations, towards other and distant cultures, and that “charity” and “altruism” can be transformed into “distant-love”, complementing Kant’s ethical imperative (imputation) with an ecological imperative, bringing in responsibility related to time and space.

This is the link to not only the idea or concept of sustainable development towards a better future, but also to the concept of Corporate Social Responsibility. Organizations are structurally embedded in the society – first of all, they are connected to their stakeholders. Considering a (more sustainable) future, organizations are responsible for maintaining their business (economic responsibility), their members/employees (social responsibility) and environment, resources and neighborhood (environmental responsibility). The official definition of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) comes from the World Business Council:

CSR

is perceived as “the continuing commitment by business to contribute to economic development while improving the quality of life of the workforce and their families as well as of the community and society at large” (World Business Council for Sustainable Development, 1998).

CSR, similar to sustainability, is often subdivided into three dimensions of responsibilities: social, economic and environmental responsibilities. Together, these three dimensions constitute the so-called triple bottom line of CSR (Elkington, 1994). IN most of the CSR concepts, sustainability is described as the principle of action that drives engagement and the development of management concepts and programs when an organization wants to take their responsibility (see fig.).

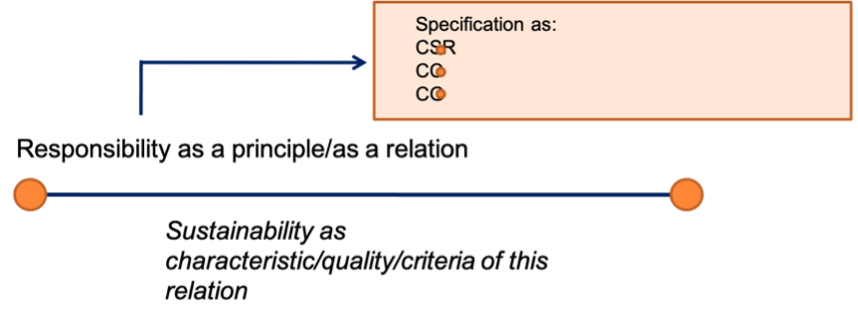

Figure: “CSR and sustainability” by Franzisca Weder 2023

Fig. 1 shows, that however the responsibility of an organization towards the society is described (CSR, Corporate Citizenship etc.), responsibility describes the relationship between an organization and its stakeholder, sustainability describes why and how this responsibility can and should be taken, the ‘quality’. Sustainability as normative framework or regulatory idea determines the character of and the criteria used to evaluate the relationships.

If sustainable development is what drives an organization, which is institutionalized in the organizations’ or corporations’ goals, then this creates certain responsibilities – for the environment (to treat resources in a certain way), for the society and individuals (make employees want to stay) and for the organization and maintaining the organization itself (economic responsibility). This is further explained with the following example:

Case Study

Photo by Franzisca Weder 2023

This is Billy, probably the most famous bookshelf on earth. You can get Billy at IKEA, a company that is apparently doing quite well in 2021, not only but mainly because of a scandal regarding the wood they used for creating Billy and his furniture-friends some time ago.

Today, they seek to create a positive impact with everything they do and are a forerunner in terms of customer engagement and recycling; 98% of the wood used for IKEA products now comes from more sustainable sources (FCS-certified/or recycled), supporting human rights in their partner countries – but communicating it as being on an exciting journey – and not there yet. Even if they inspire people to recycle their products and raise awareness, still their main challenge is and will be responsible sourcing, a sustainability issue at the core.

Not only IKEA, but all corporates with 500 or more employees, need to report their activities (Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) standards); the most common examples for CSR activities are: reducing carbon footprints, improving labour policies – and expecting their stakeholder to do the same – participating in fairtrade, charitable giving, community engagement/volunteering, and institutionalizing corporate policies that benefit the environment and go for socially and environmentally conscious investments.

However, recently the so-called triple bottom line of CSR, which is represented in the dimensions of social, economic, and environmental responsibilities that are allocated to organizations of all kinds and taken by (most of) them, has been further developed for instance by bringing in a fourth dimension – or to rather get away from the three dimensions, pillars or perspectives to a more circular model (see figure below).

Figure: “Doughnut Economics“, by DoughnutEconomics, is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The Doughnut consists of two concentric rings; the inner circle is the social foundation. It describes the dimensions and related considerations that ensure that no one is left falling short on life’s essentials. The outer circle is the ecological ceiling, that marks the dimensions that should help to ensure that humanity does not collectively overshoot the planetary boundaries that protect Earth’s life-supporting systems. From a sustainability perspective, any action (projects, activities, organizational behavior) should happen between those two boundaries, in the so called “safe and just space”. The doughnut model was developed by the Oxford economist Kate Raworth, its main goal is to re-frame economic problems and set new goals and adding measures such as jobs, education, food, access to water, health services and energy helps to accommodate an environmentally safe space.

The doughnut model still represents an economic and therefore resource oriented perspective on nature. However, there are other disciplines and perspectives that further developed the three-dimensional sustainability thinking, adding for example a cultural or communicative dimensions to CSR and sustainability.

The lady …

I was confused and suddenly recognized that I was standing next to an ant nest; shaking my leg didn’t really help … I had to move around the lady with the bike to get away from the ants without interrupting the conversation.

What was that? Is there a fourth pillar of sustainability?

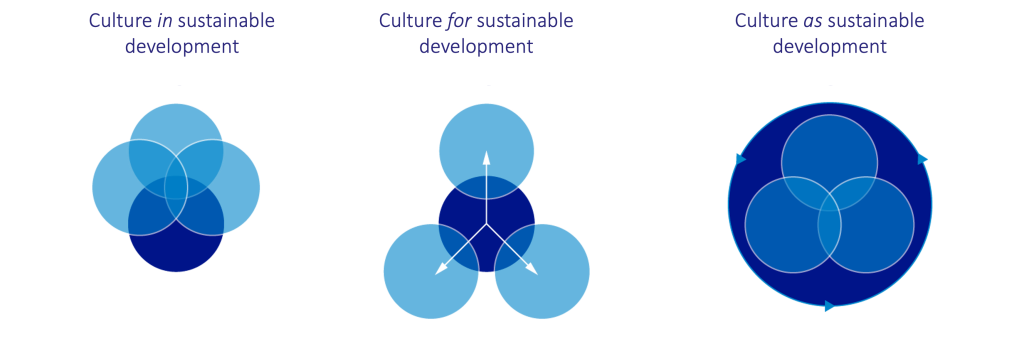

Yes. A cultural dimension for sure. Several scholars have worked with and on the three pillars or dimensions of sustainability. The most prominent attempts to expand on this triangle are those who conceptualize ‘culture’ in its different meanings in sustainability. A cultural perspective on sustainability can either be that culture is the fourth pillar and therefore, we need to conserve, maintain and preserve cultural capital in different forms as arts heritage, knowledge and cultural diversity for the next generations (Soini & Dessein, 2016) (see fig., first diagram). There is a second stream of thinking, that refers to culture as mediating the other three dimensions; culture (material and immaterial) play an essential role as a resource for economic development, cultural values need to be considered in all the other dimensions. Lastly (also in fig.), there is a more holistic perspective that conceptualizes culture itself as sustainability which leads us to our understanding in this book. From this holistic perspective, sustainability is embedded in our culture it is cultivated and normalized and leads us through transformation processes and to an eco-cultural civilization.

Figure: “Culture and sustainable development” by Franzisca Weder

This cultural perspective is not the only way of criticizing the “dimensions” or “pillars” of responsibility and sustainability.

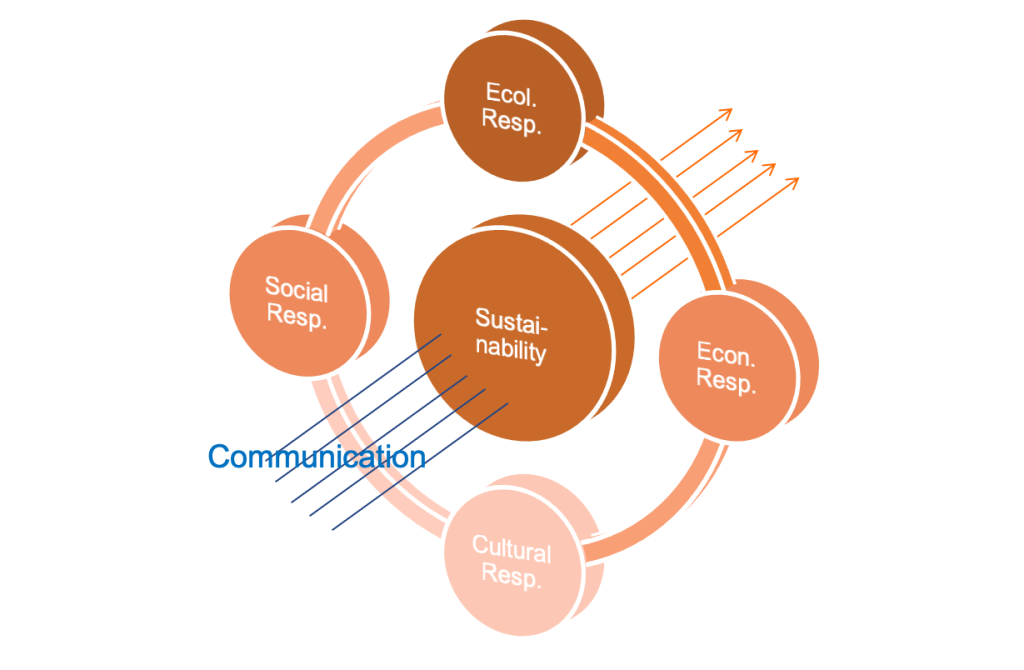

Is communication also a dimension that we have to talk about sustainability and responsibility? There have been attempts to discuss communication as forth pillar, similar to the cultural approaches discussed above. Even communication needs to be responsible and sustainable. And by the same time, from a more holistic perspective, communication does play a role in realizing sustainability in all the other dimensions, i.e. in the following figure.

Figure: “Communicative responsibility” by Franzisca Weder (based on Weder and Karmasin, 2008)

We summarize, that CSR encompasses all the practices including communication put in place by companies in order to uphold the principles of sustainable development (see above). This means that companies and organizations of all size and orientation need to be economic viable (and sustainable), but by the same time have a positive impact on society and respect, preserve and get engaged with the environment – in an ecological, space, social as well as communication dimension. In short:

CSR, sustainability & communication

management concept whereby companies integrate social and environmental concerns in their business operations and communicate interactions with their stakeholders. Sustainability guides the action, practices and programs.

Managing responsibility, that is allocated to organizations, can include several elements like implementing an ethical code, appointing an ombudsman or ethical commission and CSR or sustainability manager, establishing an ethics hotline and communicating about the code internally, installing a management tactics (fundraising, community engagement etc.) as well as communicating CSR activities publicly. The last point is of particular importance since the social and environmental commitments of organizations then offer communicative opportunities “to strengthen the social reputation and consequently the entire reputation of an organization” (Schmitt and Röttger, 2011; Röttger et al., 2014; Weder, 2020). Communication is not only inseparable from a responsibility-based management concept (CSR), much more, sustainability as principle of action can only be realized with communication – and by communicating about it -but we learn much more about that in chapter III.

Before this chapter end, we need to explain new concepts, like for example “Environmental and Social Governance” (ESG).

ESG is a concept of framework that is used to monitor and report on activities, projects and investments based on corporate policies; the idea is to make responsible behavior and activities towards the SDGs measurable and visible – and thus, to encourage companies to act responsibly.

There are again three dimensions to the overarching concept of ESG:

- environmental dimension (criteria, which include corporate climate policies, energy use, waste treatment and the treatment of animals)

- social dimensions (criteria that cover the organization’s relationship with stakeholders, includes donations, engagement, volunteering, supply chain sustainability and ethics)

- governance dimensions (ethical accountability, following reporting standards.

To summarize:

CSR is the rather idealistic, big-picture perspective on sustainability, and ESG is the practical, detail-oriented perspective on ‘realizing’ the SDGs. Thus, CSR can be seen as the precursor to ESG. Companies self-regulate and commit to sustainable practices with the aim of making a positive impact on society.

Sustainability is the umbrella that CSR & ESG fall under – and contribute to. ESG and CSR are ways that businesses can demonstrate their commitment to sustainable business practices.