Chapter 12: Swiss Hospitality Education and Students Business Projects: Action plans from the industry and for the industry

Yong Chen and Cindy Yoonjoung Heo

Yong Chen, Ecole Hôtelière de Lausanne

Cindy Yoonjoung Heo, Ecole Hôtelière de Lausanne

Abstract

Swiss hospitality education is grounded in the tradition of vocational education, exemplified by an intensive study of practical arts in a variety of hospitality contexts. As hospitality education shifts from vocational training to business administration, Swiss hospitality schools started to offer degree-granting programs, particularly bachelor’s programs, in the late 1990s. One major reason is that vocational education is incapable of addressing a lack of innovations in the industry by simply training practitioners. This situation is exacerbated not only because the boundary between the hospitality industry and non-hospitality industries is increasingly blurred but also because innovative business models that are built upon a hybrid of hospitality and technology have burgeoned over the past decade. It is more crucial than ever for hospitality education to bridge the chasm between academia and the industry through generating and propagating innovations. We demonstrate Student Business Projects (SBP) practiced by Ecole hôtelière de Lausanne, Switzerland as an example that helps to address the challenges in academia and the industry. On the one hand, SBPs aim to solve pressing problems that the industry is facing, and on the other hand, they provide action plans to the industry by highlighting the pivotal role of students in solving these problems.

Keywords: hospitality education, vocational education, Student Business Project, EHL, Switzerland

Swiss Philosophy of Hospitality Education

Swiss hospitality education is grounded in the tradition of vocational education, exemplified by an intensive study of practical arts on campus and internships in industry. Vocational education in hospitality focuses on a wide range of operational techniques in various hospitality-specific sectors, including hotels, restaurants, kitchens, bakeries, bars, and so on. It aims to teach students how hospitality businesses operate on the one hand and, on the other, to equip students with the skills they need to perform service provision as practitioners. The pedagogy of vocational education dates back to apprenticeships in Europe in the Middle Ages, when various practical arts, such as blacksmith and goldsmith, were passed on by masters to a handful of apprentices through learning by doing with their masters for a period of time. Apprenticeships had long been an efficient way of knowledge transfer, especially for practical know-how, before modern lectures took place in nineteenth-century Europe. As soon as modern tourism burgeoned in Europe in the late nineteenth century, vocational education was immediately adopted by Swiss hotel schools to train hospitality professionals, such as bakers and chefs, similar to apprenticeships in the Middle Ages. Founded by Jacques Tschumi in 1893, Ecole hôtelière de Lausanne (EHL) became the first hotel school in the world in response to a lack of skilled and qualified professionals in the industry. Swiss hospitality education takes root in the philosophy of pragmatism, which has become an integral part of hospitality education in Switzerland and by and large in Europe.

In the first place, vocational education in hospitality aims to train students as practitioners who are capable of providing and delivering service to customers with high standards. Thus, students need to practice hospitality principles and deliver services even before they go to the industry. Only when students are able to turn hospitality philosophy into a daily routine and act on it can service excellence be achieved. It is not surprising that vocational education is a key feature of hospitality programs offered in more than one hundred hospitality management schools across Switzerland. This education mode has also been exported to other countries where the development of the tourism industry depends on highly qualified practitioners and professionals to meet the needs of international tourists. In the second place, Swiss hospitality schools started to underline hospitality business administration through shifting hospitality education from hotel operation to hospitality management. This shift entails focusing on the economy of tourism and hospitality as a whole that includes various businesses instead of hotel-specific operations. This model underlines the importance of degree-granting programs in hospitality education besides the long-standing vocational diplomas.

From Vocational Education to Hospitality Management

Despite the fact that many hospitality schools have realized the importance of business administration education, the tradition of vocational education has restricted the scope of hospitality education and the academic level of programs in Swiss hotel schools. Swiss hotel schools have for a long time been offering diplomas. For instance, EHL did not offer a bachelor’s degree programs until 1998. Its two degree programs, the Bachelor of Science (BSc) and the Master of Science (MSc), are aimed primarily at attracting international students. The bachelor program, in particular, lies at the heart of the Swiss hospitality education and attract the lion’s share of international students. It is worth noting that vocational education and business administration studies are not substitutes. Instead, they are complementary in degree-granting hospitality programs. Vocational education is valued by all hospitality schools across Switzerland, and it usually serves as the basis on which business-related courses are built. On the one hand, the integration of vocational education is one the most important features of Swiss hospitality education even for master’s programs. On the other hand, due to the component of vocational education, hospitality management is set apart from business administration in provided by business schools in universities.

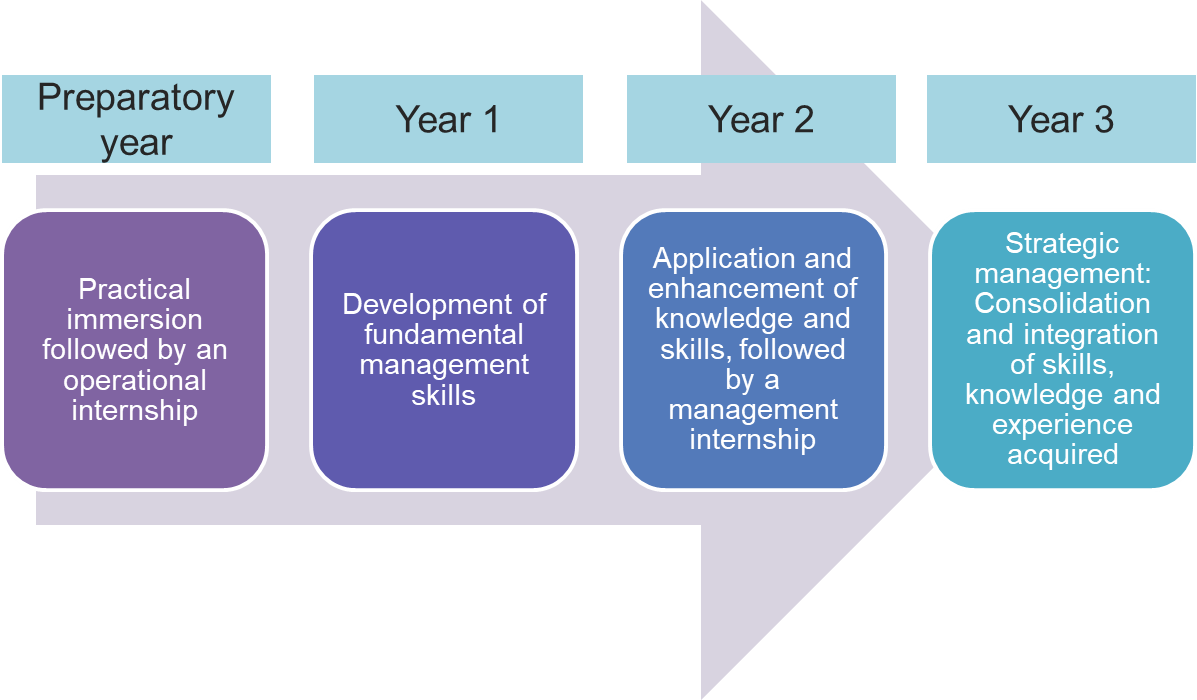

The advantage of bachelor’s education in hospitality management is that it integrates intensive business studies and a wide range of vocational education. For instance, at EHL a bachelor’s program runs three years, which is built upon vocational education in the preparatory year (Figure 1). The preparatory year’s study introduces students to basic skills and culture of the hospitality and tourism industry. It can compensate for one year of professional experience, which is a prerequisite for students to enroll in a bachelor’s program. In the preparatory year, students need to rotate among 20 workshops in the campus’ diverse food and beverage outlets, including a gourmet boutique, pastry, and Michelin-starred restaurant, and room division department to learn about hotel and restaurant operations. The preparatory year is followed by an operational internship for six months in industry. Year 1 is the first year of bachelor’s programs, which aims to develop students’ fundamental management competencies by immersing them in an intensive study of business administration courses. These courses are in three modules. One module focuses on the foundation of hospitality management, with courses including marketing, economics, statistics, finance, and accounting. The second module teaches business tools and analytics, highlighting a series of key management courses, such as revenue management, corporate strategy, human resources management, and so on. The third one is to leverage students’ communication skills by providing business communications courses.

Figure 1. Bachelor of Science in Hospitality Management (EHL)

Year 1’s courses are similar to those offered in business schools, where students learn various business foundation subjects. These courses aim at laying a management foundation for students’ second internship that is dedicated to business administration in the industry. In this sense, hospitality education is more than training practitioners but nurturing managers and business leaders. The role that vocational training plays is to consolidate the management of hospitality businesses. Year 2 is devoted to building up students’ ability to apply knowledge and solve problems. To achieve this goal, a majority of courses are application-oriented, including a wide range of business analysis courses, such as revenue management, managerial accounting, digital marketing, real estate finance, and so on. This year is followed by the second, and the last, internship for another six months. Year 3 aims at achieving the highest goal of hospitality education, helping students to develop theory-application synthesis and strategic management skills. Students should be able to synthesize theories from different courses and translate them into business solutions. Also, students should be able to take a strategic perspective to analyse the macro-business environment in which the industry operates. In the final year, students can choose to complete an individual thesis or a group project, which we shall address in detail, for fulfilling the bachelor’s degree.

Practitioners, managers, and leaders

There is no doubt that vocational education has earned Swiss hospitality education an international reputation especially for providing talents for industry. To truly master the art of hospitality management requires students who are dedicated to working in the hospitality industry to be practitioners in the first place. The culture of hospitality and services is thus nurtured through students practicing the philosophy and principles of hospitality management, helping students translate the principles into action. While the principles of hospitality operations can be taught in a classroom, they must be learned on a daily basis in the industry, which is why vocational education cannot be downplayed. A mastery of practical arts lays a solid foundation for students to excel in theoretical courses and internships. This action-oriented approach helps students translate what they learn in classroom to a working environment, aiming at integrating business intelligence and practical, hands-on knowledge. As an extension of vocational education, internships are completed at different stages of a bachelor’s program, which are designed not only to help students apply what they have learned in the classroom but also to let them bring questions from their internships back to the classroom at the later stage of their study. Students are therefore able to find solution to these questions when they are enrolled in more advanced courses.

Swiss hospitality schools not only need to train managers who are competent in dealing with operational routines but also nurture leaders who can rapidly respond to industry trends and ultimately change the industry for the better. This is because the hospitality and tourism industry has today become increasingly complex. Context-specific practice and know-how is by no means adequate. The past decade has seen an increasingly deep integration between different industries, with the boundary between hospitality and other sectors becoming blurred. For instance, Swiss manufacturing sectors, such as watchmaking, have started to incorporate hospitality culture into their daily operations. Industry practitioners have realized the strategic importance of creating a consumer experience by incorporating a component of hospitality in their products and customer solutions. This evolution has challenged the status quo of hospitality education which has long focused on industry-specific management and hotel-specific operation. The success of hospitality businesses depends on managers’ ability to transfer what they learn in hospitality to other industries. Entrepreneurs have provided compelling evidence that hospitality education should also cultivate a culture of innovation that is fertile to all businesses in the experience economy. The question is how hospitality education can respond to this change and respond to it swiftly, and how the chasm between hospitality education and industry needs can be bridged by centering on students.

Student business projects

In 2000, EHL launched what is known as Student Business Projects (SBP), which is a telling example of student-centered innovation. SBPs are mandated to final-year students as a partial requirement for the bachelor’s degree. Above everything else, SBPs enable students to generate economically viable solutions to real-world problems, thereby transferring ideas from students to the industry. Three criteria are set to ensure that SPBs are action plans from the industry and for industry. First, SBPs generate solutions to problems that companies encounter in the industry. To this end, a special taskforce consisting of five specialists is set up to promote the SBP concept to the industry and to gather problems and requests from it. Then the taskforce winnows down problems that are suitable for SBPs in terms of academic standard for a bachelor’s degree and industry relevance. Second, SBP clients are charged a consultation fee, and hence there is no difference between an SBP and a consulting project furnished by professional consultancy firms except that students are the consultants. Third, an SBP requires the engagement of the client in the whole process. In particular, the client needs to provide student consultants with the information they need about the company and the problem. Students have regular meetings with the client in order to obtain feedback from the client and ensure that the project is on the right track. Client engagement ensures that the deliverables meet the expectation of the client.

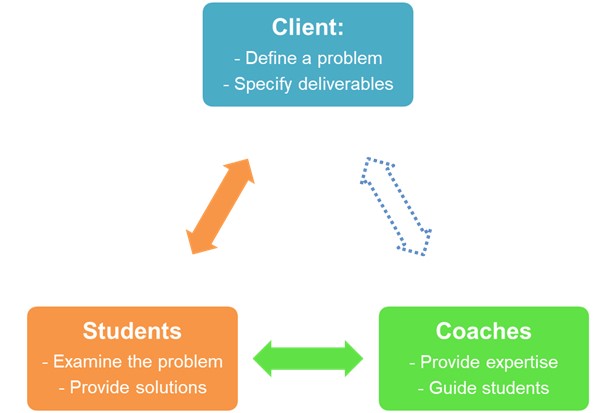

An SBP project entails coordination between three parties, a client, a team of six final-year students, and two faculty coaches. A client commissions students to fulfil a project through the school. A team of six final-year students act as consultants, selecting an SBP based on their academic interests, expertise, and background. Two faculty coaches are assigned to guide students by providing expertise as well as safeguarding the quality of the project. Figure 2 shows the relationships of the three parties. The principal relationship is between students, who provide ideas and solutions, and clients, who have a pressing problem that requires a solution. In this regard, clients believe that the solutions should be provided by students instead of industry consultancy. Faculty members are supervisors and mentors who provide expertise and guide students as they carry out their SBP mandate. Since faculty members are not directly involved in the project nor have contact with clients, SBP consultancy underscores the pivotal role of students as the main contributor of business plans.

A typical SPB project works as follows. A client proposes a problem and details the deliverables of solutions. A group of six students select the client and acquaint themselves with the problem and deliverables. They have nine weeks to propose a solution that can be implemented by the client. A well-crafted and feasible solution requires students to clearly identify the problems, contact the client on a regular basis and administer a series of market research activities.

Figure 2. An illustration of Student Business Project (SBP)

We take a SBP project completed by a team of students in June 2018 for an illustration. The client was a company providing skiing and hotel services in the region of Flims-Laax-Falera in Switzerland. Due to seasonal demand, a majority of hotel businesses were contributed by Laax, which was only one of the three areas in which the company was operating. The company wanted to turn the whole area of Flims-Laax-Falera into an all-year-round destination, and believed that the Chinese market would help achieve this goal. The deliverables of the project included examining the feasibility of the Chinese market to Flims-Laax-Falera and analysing Chinese travellers’ behavior. Specifically, the goal was to identify consumer segments that the company could target and provide recommendations regarding how to attract Chinese tourists and sell vacations to different segments in order to reduce demand fluctuation. In the nine weeks, students were scheduled nine weekly meetings, each for one hour, with two faculty coaches to obtain academic and administrative support. These meetings were necessary for the coaches to know the students’ feedback and provide disciplinary knowledge. Besides extensive secondary research, the students accomplished two field trips to the company and the destination, administered two surveys collecting information of prospective Chinese tourists, and organized 10 interviews with industry professionals who were experts of the local tourism market and Chinese tourists.

The outcome of this SBP was a 90-page long consultancy report, including references and appendices. In this report students detailed deliverables in four parts, namely (1) introduction, (2) research methodology, (3) research findings, and (4) recommendations. Of the client’s primary interest were research findings and recommendations. In research findings students presented the results of the surveys and secondary research, including the evolution of Chinese tourism market, Chinese consumer behavior and middle-class consumption, and Chinese tourists and their preferences. This part set the background of the Chinese market for the client and drew the relevance of the Chinese market to the client’s product. In the recommendation part, students provided suggestions which included general recommendations and specific market segmentation strategies. They suggested segmenting Chinese tourists into nature lovers, snow lovers, outdoor enthusiasts, and snow sports enthusiasts, and proposed solutions that the client could implement in operation. While the consultancy report was the major part of the SPB, the project was officially concluded by inviting the CEO, or other management, of the company to campus to assess student presentation. The SBP was evaluated by the client and two faculty coaches on aspects regarding final report, presentation, and project management. The feedback of the client during the presentation and the report was communicated immediately to the students. Clients often appreciate the passion and creative thinking demonstrated by student consultants, especially when the final research results fit the scope of the project.

Academic-industry collaboration through students

The SBP consultancy has accomplished 1,100 projects for 650 companies or organizations in a variety of industries since it was launched in 2000. EHL now hosts between 80 and 100 projects each year. One may believe that SBPs are favoured by small enterprises and start-ups, which often lack financial resources to commission their projects to big consultancy companies while craving innovation and solutions as large corporations do. On the contrary, our results suggest that big corporations account for the largest proportion of all clients (22%) as shown in Table 1. Big corporation and medium businesses combined account for 43% of all clients, followed by entrepreneurship with 18%, and small businesses with 17%. There are perhaps two reasons why big corporations are in favour of the SBP consultancy. One is that big corporations become well aware of the importance of hospitality in creating consumer experience despite the fact that they do not render hospitality goods and services to their customers. For instance, the Swiss watchmaking and financial industries value luxurious experience to their customers through implementing the principles of hospitality. The other reason is that the scope of tourism and hospitality has been expanded with the integration of hospitality and technology, exemplified by new businesses such as Uber and Airbnb. Students are perhaps the most competent consultants for these companies, because they are the key consumers and know these products better than anybody else.

Table 1. Types of SBP clients

| Types of clients | Proportion | Size of the company | Example |

| Big business | 22% | More than 400 employees | Nestlé, UBS |

| Medium business | 21% | Between 100 and 400 employees | |

| Entrepreneurship | 18% | Fewer than 20 employees | Biolia |

| Small business | 17% | Fewer than 20 employees | |

| Non-profit | 6% | ||

| Academic institution | 6% | ||

| Municipality | 6% | ||

| International | 2% |

Table 2 shows the top 10 project types that are commissioned by clients of SBP. These projects can be classified in three areas: (1) marketing and business expansion, (2) product/concept development, and (3) business financial feasibility. There are many requests for marketing and business expansion solutions. These requests are primarily from well-established firms in Europe aiming at expanding their businesses or brands to other countries or markets. Specifically, they need solutions regarding how to enter a new market through product reposition, extension, or franchising because the parent companies have little knowledge of the target markets. Many tourism companies, cruise lines, or destinations aiming at attracting tourists from certain countries or markets also fall in this category. Product/concept development is favoured by start-ups in cases where they aim to develop new products, such as environmentally friendly food, craft beer, and so on, while have little knowledge with regard to consumer responses. Thus, understanding consumer needs becomes crucial. This also includes, as we experienced over the years, that many engineers who developed cutting-edge products but had no idea how to market them. Financial feasibility study addresses the needs of new products and business expansion and the profitability in a given period.

Table 2. Top 10 project types

| Type | Deliverables | Industry |

| Business plan | Market research in new markets, business expansion, consumer acquisition strategies | Hospitality, non-hospitality |

| Concept creation | Develop a product/service concept that can be implemented by clients | Hospitality, non-hospitality |

| Customer experience | Service delivery process, customer satisfaction management | Hospitality, non-hospitality |

| Event concept | Event and marketing proposal and strategy | Hospitality, tourism |

| F&B concept | New products and innovation in restaurant and F&B of hotels | Hospitality |

| Financial feasibility study | Feasibility analysis of new business and product | Hospitality, non-hospitality |

| Hotel concept | Hotel branding, hotel business expansion | Hospitality, non-hospitality |

| Market research | Consumer study, market segmentation | Hospitality, non-hospitality |

| Marketing & sales strategy | Marketing, promotion, revenue management | Hospitality, non-hospitality |

| Product development | New product development, new product concepts | Hospitality, non-hospitality |

Conclusion

The hospitality and tourism industry requires various innovations ranging from service provision, customer management to distribution design while the industry itself may not be able to generate this type of innovation. Scientific research and consultancy by involving students can help to address the lack of innovation and entrepreneurship in tourism and hospitality. It is difficult to practice innovation in service industries like hospitality and tourism where operation seems to override everything else. Therefore, applied research and consultancy from academic institutions can fuel industry development by incubating innovative ideas in laboratories and turn these ideas into business solutions and entrepreneurship. SBPs reward to students, the school, and the industry simultaneously. For students an SBP is a milestone project that provides them with tremendous opportunities to apply their creative ideas and fulfil the requirements of their bachelor’s degree. Clients can obtain solutions at a lower cost and deep understanding of consumers. SBP are in essence user-generated innovations because students not only the innovators but also tomorrow’s customers. For the school, the relationship between academia and industry can be extended from operation and internship to consultancy and innovation.

Swiss hospitality education has evolved from the predominance of vocational education to a blend model of arts and sciences. These changes reflect the changes in the industry over the past few decades and contributes to the development of the industry as well. The orthodox hospitality industry today is also gradually expanding to include not only hotels and restaurants but also airlines, casinos, cruises, and all businesses insofar as they addressed the needs of travellers and tourists in one way or another. Therefore, the boundary of the tourism and hospitality industry is blurred especially when vocational education is giving way to hospitality management of a wide range of businesses. What the hospitality industry evolves in future decades is perhaps a shift from providing hospitality- or tourism-specific services to creating customer experiences in various contexts where human interactions occur. From a disciplinary perspective, hospitality management needs to solve problems in any industry or for any business in which hospitality is an integral part of product offering. Therefore, we should also expand the scope of hospitality management from vocational training to business administration, thereby furnishing the industry with innovative ideas and business acumen. Hospitality education should focus on training students not only as practitioners in specific hospitality domains but also innovators and leaders in the industry as a whole.

For students, obtaining an education in hospitality does not mean that students’ career development is only restricted to hospitality or tourism. According to EHL, around 46% of its graduates are employed in non-hospitality industries, such as consulting, banking and finance, real estate, healthcare and education. Hospitality education at EHL provides students with extensive coursework in a broad business arena, which helps sharpen their business acumen and competences in a wide range of non-hospitality industries. These skills are honed by attending business courses that are not industry-specific, but can be applied to a wide range of industries. In this regard, there appears to be no significant difference between hospitality schools and business schools. What matters is whether students can sharpen their analytical skills and business acumen in applying what they learn to the fields of hospitality and tourism. These skills can be applied to other industries as well, indicating that students are resilient and flexible in operating businesses in a multi-business environment. The question is how to prepare students with business skills and how to test the suitability of students for the industry. The SBP consultancy is one of the answers.

References

Chen, Y., Dellea, D., & Bianchi, G. (2019). Knowledge creation and research production in Swiss hotel schools: A case Study of the Ecole hôtelière de Lausanne. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education, 31(1), 10−22.

Chen, Y., & Dellea, D. (2015). Swiss hospitality and tourism education: The experience of Ecole hôtelière de Lausanne, Tourism Tribune, 30(10), 5−9.