Chapter 1: Practical Learning in Hospitality Education

Lianping Ren and Bob McKercher

Practical Learning in Hospitality Education – From pedagogical debate to wide adoption

Lianping Ren, Macao Institute for Tourism Studies

Bob McKercher, University of Queensland

A long standing debate has occurred in hospitality degree programmes about the need for and merits of embedding practical training components in what are ostensibly management degrees. The debate goes to the heart of training versus education quandary facing hotel management, hospitality and tourism programmes. It also leads to some long standing questions raised by some old school academics about the legitimacy of offering such degree programmes at the university level instead of at technical college level, where some feel they belong better. The ones who argue against degree level programmes feel management degrees should focus on theory, with the assumption that the graduate would be able to apply the theories in their workplace (DiMicelli, 1998). Those in favour of including practical components in degrees hold the “learning by doing” view. Since these programmes are heavily professionally oriented, their main objective should be to produce work ready individuals who possess both theory and practical skills (DiMicelli, 1998; Ruhanen, 2005).

Fortunately, this debate has been largely resolved over the last 20 years (DiMicelli 1998) as universities appreciate the need to ensure their graduates have some real world skills to complement the more theoretical aspects of their education. In fact, more and more business schools are insisting their students complete a traineeship or practicum of some sort prior to graduation, regardless of their discipline. Indeed, in many ways, hospitality education has been at the forefront of the move to integrate training and education with the recognition that a practical learning component is an inseparable aspect of comprehensive hospitality education curriculum (Zopiatis and Constanti, 2012). Moreover, placements have been shown to motivate student learning by enhancing understanding and facilitating confirmation of knowledge learned in the classroom (Stansbie, Nash, and Chang, 2016), prepare students to be work ready (Spowart, 2011), and help them achieve a greater range of competencies, including leadership, management skills, and problem solving skills, which is somewhat more difficult to acquire via classroom teaching (Lin, Kim, Qiu, and Ren, 2017; Gurman, Barrows, and Reavley, 2013). In fact, a positive practicum experience increases commitment to this field and enhances career aspirations (Yan and Cheung, 2012).

Various terms have been used synonymously to describe practical learning components, with the most frequent being work-integrated learning/education (WIL/WIE), work-based learning (WBL), project-based learning, practicum, internship, work placement, job shadowing, and sandwich courses, to name just a few. Others include sandwich years, practical learning, experiential learning, lab-based learning, and service learning and the like. Each in realty is talking about the same opportunities for students. They key to a good practicum, though, is that it must involve far more than simply gaining work experience. Instead, successful practicums must have clearly defined pedagogical goals, where the work-related element is tied tightly to the curriculum so that the student acquires programme related knowledge while simultaneously developing some practical skills. It sounds simple, but as mentioned repeatedly throughout the chapters in this book, the achievement of such a goal requires a close tripartite relationship involving the student, the institution (and teacher) and the organization where the practicum takes place.

The challenges faced by all institutions are, first, to find a balance between educational and vocational ideals and second to provide space in the curriculum framework to draw the two together (Dredge et al 2012). As a result, no single ‘best’ model exists. Instead, as discussed in detail in this book, a wide array of options is applied, that are limited only by the institution’s imagination and resources. Some are credit bearing, while others offer ‘workplace’ credits that are counted above and beyond the normal credit load taken to graduate. A number of programmes offer a single practicum; others combine in-house labs with an external practicum and; others still insist their students complete two practical components to satisfy the degree requirements. In terms of when the practicum occurs, some curricula place it after all coursework has been completed, while others embed it in the curriculum by making students complete it as a “sandwich” obligation. The duration ranges anywhere from one to twelve months.

However, no matter how well-intended the above training programs may be from the start, they do not necessarily turn out to be an all-happy ending. Employers may complain that graduates lack certain competencies and that they are not ready for the workplace (Spowart, 2011). On the other hand, students may claim that their needs are often not met (Zopiatis and Constanti, 2012). The failures may be explained by less structured nature of the programs, insufficient training, lack of support from both the work place supervisors and school teachers, less effective coordination between the schools and the hospitality firms, less engaging work arrangement, unfavourable working conditions, and less inspiring workplace interaction etc. In addition, different priorities and goals among institutes, hospitality firms, and students cause problems as well. For example, in terms of internship duration, industry prefers longer traineeships, while some students prefer shorter ones, especially if the practical component is not well designed. Institutes and students desire job/duty rotation during practicums, while hospitality firms may find it cost-ineffective to do so. Hospitality firms welcome practical programs that feature cooperation, duration and mentoring, but not every institute has the same level of commitment.

How to use this book

To evaluate the effectiveness of the internship / practical programs, it is necessary to look into is the gap between “what the students have learned in school” and “what is required by the internship providers”, the gap between “what the intended learning outcomes are” and “what is achieved in the workplace”, and the gap between the program designed by the institute and the program that is welcomed by the hospitality firms.

Taking the above together, this book looks into scenarios, conditions, and rationale associated with practical learning in hospitality education, specifically the pedagogies adopted, the development and operation of the training facilities and teaching hotels, issues with off campus training programs, key players in the tripartite relationship, and ultimately the effectiveness of such programmes. The book takes an international perspective, and considers all possible contexts. The ultimate purpose is to provide references on various aspects of practical learning in hospitality, so as to facilitate decisions on the programs and facility design.

The book provides a lens to examine the hows and whys of a range of practical learning models adopted by more than 20 institutions located around the world. Each chapter is designed to encourage the reader to read and reflect on the merits and possible weaknesses found in each of the models. Indeed, one of the key features of the book is the request for each author to include a reflective section at the end of each chapter that enables them to critically assess what works and what can be improved in their own institution’s situation.

Structure of the Book

The chapters written by the many contributors to this book explore the diversity of models available and discuss their relative strengths and challenges. The book contains 22 reflective case studies and research reports from five continents and more than a dozen economies. It is organized into five sections:

- Part 1 – Practical learning in on-campus commercial hotels

- Part 2 – Practical learning in on-campus training hotels

- Part 3 – Practical learning in on campus training units

- Part 4 – Off campus practicums and internships

- Part 5 – Internship experiences from students and industry.

Parts 1 to 4 present 17 different scenarios that can assist the reader to understand how different approaches work, whether it is to develop a commercial hotel on campus, operate a small training hotel, make use of food and beverage labs or student consultants or outsource students to industry as part of a practicum placement. Part 5, is perhaps, most instructive, for it allows the students’ and industries’ voices to be heard. Each section of the book is described briefly below.

Part 1 – Practical Learning in On-campus Commercial Hotels

The first part of the book examines some of the challenges and opportunities involved in developing commercially operated hotels on campus. Two models exist: developing a stand-alone private brand or encouraging a national or international brand to develop a property on campus. Chapter 2 presents an overview of both models and lists a range of so called captive hotels located at American universities. Chapters 3 and 4 examine some issues related to private brands, Chapter 5 discusses issues of taking a brand from a major hotel operator, while Chapter 6 discusses career opportunities that an on-campus commercial hotel provides to non-hospitality students.

A number of benefits are associated with developing and operating hotels on campus. First, closer integration between the curriculum and the hotel operation becomes possible as does integration of hotel personnel as part of the teaching team. Second, a wider range of skills can be developed, some of which are not so easy to develop in other formats. Third, on campus hotels can strive to incorporate the programme’s overall philosophy into the training component of the programme. For example, the hospitality programme at Cornell University has fully embraced its “Life is Service” motto in the Statler Hotel (Chapter 3), while the School of Hotel and Tourism Management at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University highlights its “Leading Hospitality” brand through such programmes as its Elite Management Programme. Other benefits attached to having on-campus hotels, include having an added amenity to the university, revenue generating opportunities, and better public-private partnership opportunities. Interestingly, as discussed in Chapter 6, operating an on-campus hotel even at a university that does not have a formal hospitality programme encourages some students studying other disciplines to consider tourism and hospitality as a career path.

But, developing a commercial hotel is not without its challenges, most of which relate to development costs and the need to run profitably. As a result, these types of developments tend to be limited to well-resourced universities, specialist hospitality institutions or universities that have identified tourism and hospitality as a core strategic objective. Beyond cost considerations, the learning curve is also steep as university administrators and most department leaders are not experienced in hotel property development. In addition, operational costs are high as properties must run independently, and cannot rely on corporate offices to assume some on and off costs. Lastly, staffing can be a challenge, for it is sometimes difficult to recruit senior staff and convince them to leave the security of working for a national or multi-national organization.

It is for these and other reasons that a number of universities have opted to go with the option of encouraging branded properties to locate on campus and provide training opportunities. Chapter 5 presents an excellent case of the opportunities and challenges involved in such a project. The main benefits relate to resolving the types of issues faced by private brands. The expertise exists, hotels are operated as parts of chains, with all the benefits accrued to this model, staffing is often not a problem. Properties are run on a turn-key basis from opening to operation. The risk of course is that students will get a cookie cutter experience and learn only the practices adopted by one brand.

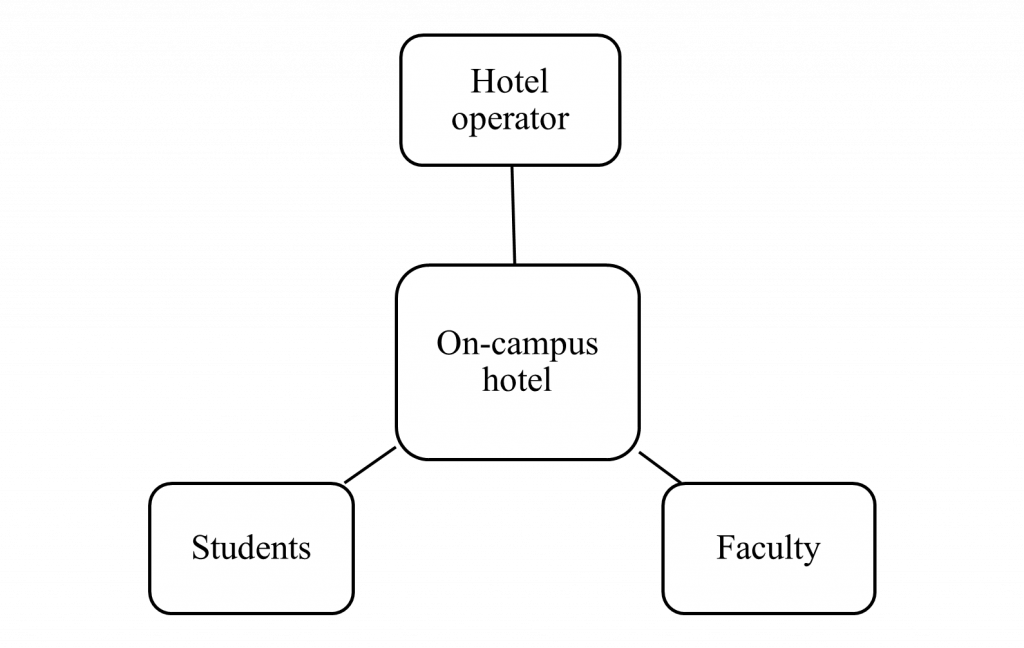

The administration of the training programs in on-campus hotels has its own challenges. As reported in Chapter 2, for example, scheduling and coordinating difficulties must be resolved. Goal misalignment may also occur, where the hotel’s business needs may clash with the department’s educational needs. The role of hotel staff in the students’ learning process needs to be suitably defined, so as to enhance their practical learning experience. A further challenge is that not all hotel leaders are suitable to work in a captive hotel, for members of the management team must be willing to devote more time to facilitating learning and deal with rapid turnover of students who complete their traineeships just as they become competent employees, only to have to deal with a new group of inexperienced students. This view was echoed by authors in Chapter 5. The school faculty need to work closely and interactively with the hotel team. Sometimes, resistance from students can be a serious issue to be tackled. In a word, a synergy is desired among the key players as exemplified in Figure 1. The ICON model presented in Chapter 4 provides a scenario where this synergy could be well achieved. The success of the ICON model can be partially attributed to its innovative affiliation structure.

Figure 1 Key players in on-campus hotel training programs

Part 2 – Practical Learning in On-campus Training Hotels

An alternative model adopted by a number of providers is to develop their own small training hotels where return on investment assumes a lower priority than the achievement of educational outcomes. Faculty members are often heavily involved in the hotel management, and the majority of the hotel guests are school visitors, parents or students. There are a few merits attached to this type of hotel. It is easier to conceive and develop, costs are lower and construction time shortened. Moreover, it can be administered as an integral part of a larger hotel or hospitality programme, ensuring educational goals are attained. As cited in the case study from Macau, sometimes existing buildings can be repurposed as boutique hotels. There is often less pressure to perform financially, enabling a three-phased practical learning process including: lab-based learning, practical learning in the training hotels, and ultimately an off-campus internship. Industry likes this model for students tend to be better prepared to perform well once they embark on their internship.

However, their small size, management style, and the fact that many do not or cannot operate at international standards may contrast with the reality students will face when they enter the commercial world. Often, there are limited functional areas in the hotels, so the students are not exposed to a full range of experiences. Moreover, mistakes are tolerated, which can lead to bad habit development. The small scale of the hotels and their training priority lead to another problem – fluctuating occupancy rate – which negatively influences student learning experiences as student learning may be inhibited when few customers check-in.

Part 3 – Practical Learning in Training Units

With or without an on-campus hotel, many institutes build training labs or training units on campus, including kitchens, bakeries, training bars, training restaurants, wine labs, tea labs, food labs, and training guest rooms. These labs and training spaces are used for specific courses and exercises. Two chapters examine different approaches taken primarily in food and beverage labs, while a third discusses the use of students as consultants as a means of honing their strategic skills.

A lab-based environment allows more structured teaching and learning, focused skill development, and trial and error practices, with instant feedback between the instructors and learners. Honing skills in a planned and step-by-step way is one of the advantages of learning in the training units, as it is illustrated in Chapter 11. The cost for developing labs and training units is relatively low and justifiable. However, various challenges are attached to the operation of labs and training units. Examples include staffing issues, as discussed in Chapter 10. Striking a balance between staffing cost and quality of practical training is a key concern. This dilemma is typically felt in the decision of whether to hire full time instructors to supervise the lab work or have existing faculty members, part-time instructors and/or graduate students help with the supervision. A further decision must be made as to whether the labs are closed with no outsider involvement or to open them to the public and operate as revenue generating restaurants. Other challenges include inter-departmental communication on the operation of the labs and scheduling of the training sessions.

Some programmes opt for higher level skill development by enabling students to assume the role of managers or consultants and solve real world problems for real clients. This model has been developed effectively by the Ecole Hôtelière de Lausanne (EHL), Switzerland. This Chapter works the reader step by step through their model.

Part 4 – Off Campus Training Programs

Not all institutes can afford to establish on campus hotels and commercial or non-commercial training facilities. Instead, they opt to send their students out to industry to gain experience. Indeed, even programmes that do offer on-campus labs also make extensive use of off campus practicums and traineeships. Here, institutes choose to establish collaborative relationship with hospitality firms. Chapters 13 through 17 discuss a range of options developed by universities in Canada, South Africa, the UK, Singapore and the USA.

Progressive hospitality firms are supportive of these initiatives, for they can help resolve short term staffing issues, provide a valuable opportunity to recruit staff on graduation, select through careful observation, and also benefit from the chance to interact with hospitality institutions (Yan and Cheung, 2012). Training activities and programs offered by industrial partners can include anything from site visits, guest lectures, and workshops, to longer-term practicums and internships. In recent years, industry has begun taking a more proactive approach to establish training programs by actively setting them up on their properties and signing commercial agreements with educational providers. The key to successful off-campus internships is the ability to integrate desired learning outcomes there with practical work experiences. Chapter 13 illustrates such a programme. In addition, cross cultural internship opportunities have gained popularity in recent years. The hospitality industry is international by nature, so gaining cross cultural competency is one of the motivations for the students to do so.

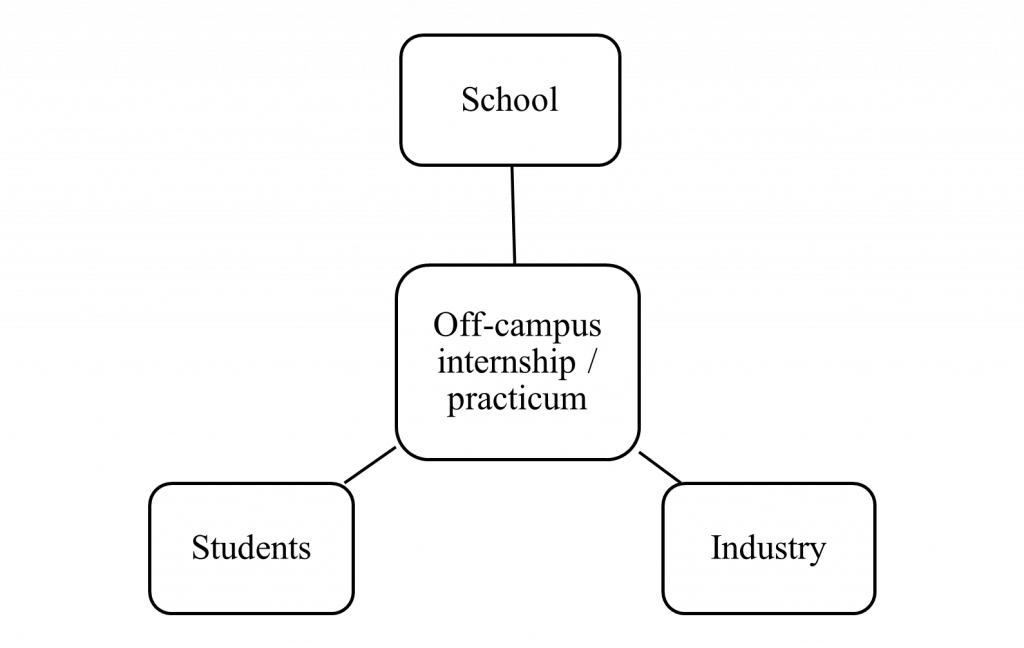

Success depends on a tripartite relationship among the school, students, and the industry as highlighted in Figure 2. The most prominent advantage of the off-campus training programs is that they provide a real business environment which many on campus training facilities fail to provide. But issues and challenges can arise related to this kind of training as well. For example, goal misalignment can occur between the institute and the firm, where the institute has a set of intended learning outcomes that they expect the students to achieve, while the hospitality firm may have conflicting needs, especially related to filling short term staffing vacancies that may not be related to the student’s education. The net result is that students end up with a single position that only performs mundane and less intellectually demanding tasks such as cleaning guestrooms and waiting on dinner tables. On the other hand, employers may complain that the students are not ready when they take up their internship. In order to achieve desired outcomes, Chapter 14 which explains the University of Guelph’s Co-op Program provides an example of how to resolve such issues.

Institutes play an important role in administering these programmes and playing a coordinating role between students and employers. Good practices include setting up a specialized unit with dedicated teams. The role of the Work Integrated Learning Coordinator is identified to be critical by the author of Chapter 16. Apart from the internship programs implemented in the hotel firms, the School needs to provide various pre and post administrative, preparatory and assessment programmes to ensure a positive practical learning experience occurs. Chapter 15 discusses how internal collaboration can be capitalized in harnessing the students’ placement preparation process. Equally important is the post internship follow-up administration including assessment. To facilitate the entire application process, the case concerning the Singapore Institute of Technology discusses how it has created a system for the students to follow, while the institute stays in close communication with industry partners (Chapter 17).

Of course, students, the main actors in the tripartite relationship, play a critical role in benefiting from the practical programs. Being prepared, both skill-wise and psychologically (Chapter 15), and having a sufficient level of learner autonomy (Chapter 14) are important prerequisites of successful practical learning programs. Many off-campus internship programs require students to be away from home and live independently, often for the first time. This major change of life and study environment entails adaptable personality and capability.

Figure 2 Tripartite relationship in off-campus internships/practicums

Part 5 – Internship Experiences – Student and Industry Perspectives

Practical training programs aim to develop hospitality students to be work-ready for their future careers. Students acquire cognitive and professional skills through the “learning by doing” component of the hospitality curricula and develop their career smoothly thereafter. The last section of the book lets students and employers express in their own words what works well and what can be improved during the practicum experience.

Chapter 18 compares students’ pre- and post-practicum experiences and concludes that while practicums do work for many students, a number of issues that can inhibit the experience and reduce students’ commitment to the industry need to be addressed. Chapter 19 discusses how students in the University of South Pacific have reflected on acquiring employability skills including improving their own learning and performance, communication, working with others, problem solving, and application of technology. Chapter 20 reveals how students value the responsibilities that they need to take in real life business environment, which leads to a sense of achievement and a higher level of confidence in embarking a career in the hospitality industry. Chapter 21 reports on what industry feels make a good practicum student, as well as a beneficial practicum experience. Chapter 22’s case illustrates how Olivia gets well prepared for her career and find better opportunities leveraging on her experience and competencies she has obtained via practical learning activities and programs. Chapter 23 tells the story of how three students demonstrated grit and determination to overcome significant personal issues to complete their internships.

References

DiMicelli Jr, P. (1998). Blending theory and practical experience: A hands-on approach to educating hospitality managers. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education, 10(1), 32-36.

Dredge, D., Airey, D., & Gross, M. J. (Eds.). (2014). The Routledge handbook of tourism and hospitality education. Routledge.

Dredge, D., Benckendorff, P., Day, M., Gross, M. J., Walo, M., Weeks, P., & Whitelaw, P. (2012). The philosophic practitioner and the curriculum space. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(4), 2154-2176.

Gruman, J., Barrows, C., & Reavley, M. (2009). A hospitality management education model: Recommendations for the effective use of work-based learning in undergraduate management courses. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education, 21(4), 26-33.

Lin, P. M., Kim, Y., Qiu, H., & Ren, L. (2017). Experiential learning in hospitality education through a service-learning project. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education, 29(2), 71-81.

Ma, C., Ren, L., Chen, P., & Hu, R. X. (2020). Institute–Hotel Coordinating Barriers to Early Career Management—Hoteliers’ Accounts. Journal of China Tourism Research, 16(2), 297-317.

Ruhanen, L. (2006). Bridging the divide between theory and practice: Experiential learning approaches for tourism and hospitality management education. Journal of Teaching in Travel & Tourism, 5(4), 33-51.

Spowart, J. (2011). Hospitality students’ competencies: Are they work ready?. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 10(2), 169-181.

Stansbie, P., Nash, R., & Chang, S. (2016). Linking internships and classroom learning: A case study examination of hospitality and tourism management students. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 19, 19-29.

Yan, H., & Cheung, C. (2012). What types of experiential learning activities can engage hospitality students in China?. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education, 24(2-3), 21-27.

Zopiatis, A., & Constanti, P. (2012). Managing hospitality internship practices: A conceptual framework. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education, 24(1), 44-51.