Chapter 11: Use of Training Facilities in Hospitality Education: A case study of Nepal Academy of Tourism and Hotel Management (NATHM)

Sandeep Basnyat and Shiva Prasad Jaishi

Sandeep Basnyat, Macao Institute for Tourism Studies

Shiva Prasad Jaishi, Nepal Academy of Tourism and Hotel Management

Abstract

The Nepal Academy of Tourism and Hotel Management (NATHM) provides training to its undergraduate hotel management students through a range of in-house training facilities. These training facilities include training kitchens, bakeries, restaurants, bar, hotel rooms and a coffee shop, among others. This chapter explores the use of practical training facilities, especially training kitchens and training restaurants, by students and instructors at NATHM. As will be seen, the approach of participatory training employed at NATHM not only encourages students’ engagement and contributions during a training but also equips them with professional knowledge, skills and ideas that they can effectively, efficiently and creatively use in their everyday work in hospitality establishments.

Introduction

Ensuring classroom learning experiences are applicable to actual management situations has been an important issue as well as a concern for higher education institutions that provide hotel management education (LeBruto & Murray, 1994). In order to broaden students’ thinking and enable them to operate outside the existing practices and paradigms, most hotel management schools provide some form of practicum (Alexander, 2007). Hotel management is considered as a distinctive part of hospitality management education that strongly emphasizes acquiring practical skills required for the management of specialized accommodations (Higher Education Funding Council for England, 1998). Therefore, a practical element is not only a defining characteristic of hotel management education but also indicates its strong connection with the industry (Higher Education Funding Council for England, 1998). In order for students’ learning experiences to be responsive to industry demand, the development of suitable physical facilities that provide adequate training opportunities at hotel management schools plays an important role (LeBruto & Murray, 1994). This chapter presents the case of the Nepal Academy of Tourism and Hotel Management (NATHM) and explores the use of its practical training facilities, especially training kitchens and training restaurants, by both students and instructors. As will be seen, the approach of participatory training employed at NATHM not only encourages students’ engagement and contributions during training but also equips them with professional knowledge, skills and ideas that they can effectively, efficiently and creatively use in their everyday work in hospitality establishments.

The tourism and hospitality industry employs about 20% of the economically active population in Nepal, or about one million workers (ILO, 2018). As of 2018, there were 1,254 starred and non-starred hotels operating in Nepal (MOCTCA, 2019) and the average annual growth rate of the hotel and restaurant sectors was above eight percent (8%). Undergraduate and post graduate degrees in travel, tourism and hotel and hospitality management are provided by four major universities, Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu University, Purbanchal University and Pokhara University, and their affiliated colleges (Thapa & Panta, 2019). As of 2019, for example, a bachelor’s degree in hotel management was offered by 17 colleges affiliated with the above four universities (Thapa & Panta, 2019).

The Nepal Academy of Tourism and Hotel Management (NATHM) was established by the government in 1972 to provide supervisory level skill-oriented training to cater to the demands of the tourism and hospitality industry. Since 1999, NATHM started to offer a Bachelor of Hotel Management (BHM) program and from 2003, it has been offering a Bachelor of Travel and Tourism Management (BTTM) program. The BHM curriculum includes a blend of theory classes, a practicum, and industrial exposure through an internship. Students complete their undergraduate program in four years. With the launch of the Master of Hospitality Management (MHM) program in 2011, NATHM has been able to produce senior-level human resources suitable to the needs of industry. Apart from academic courses, the Academy provides regular as well as on-request craft and skill-oriented training sessions, including tour and trekking guiding, small hotel and lodge management, food preparation, food and beverage service management, front office management, and housekeeping, among others, to cater to the demands of the industry. In line with the government’s policy to diversify the tourism industry, NATHM has been conducting mobile outreach training programmes in various parts of the country. These training programmes are primarily aimed at improving small hotel and lodge management, homestay management and tour guiding skills among local residents.

Participatory training approach at the training kitchens at NATHM

Spread over one and half hectares, NATHM provides training to its undergraduate hotel management students through a range of in-house training facilities. These training facilities include five training kitchens, two training bakeries, three training restaurants, one training bar, 20 training hotel rooms and a coffee shop. A new 4-star, 82 room training hotel is under construction to provide real-time experiences for students.

This section introduces the training kitchens and their usefulness and provides details of the participatory approach of providing practical training at NATHM. The next section will focus on training restaurants.

Table 1: Training kitchens, equipment and their uses

| Training kitchen | Students/instructors who use the kitchen | Equipment in the kitchen | What students learn |

| Advanced | First and Second Semesters | Working stations with ranges, tables, combination oven, deep freezer, refrigerator and cutting equipment | Cut, chop, and trim meat, fish, poultry, and vegetables /roast, grill, and bake / artistically present the prepared food |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic | Third and Fourth Semesters | ||

| Satellite | Third and Fourth Semesters | Reheating equipment | Reheat prepared food before they are served in the training restaurants |

| Bulk | All semesters | Working stations with high-pressure ranges, tables, combination oven, deep freezer, refrigerator and cutting equipment | Prepare bulk food or a large quantity of food |

| Demonstration | All semesters | Working station with a range, table, combination oven, deep freezer, refrigerator and cutting equipment for demonstration | Recipes, menus, nutrition information, food presentation styles, fruits, vegetable and ice carving techniques, and culinary techniques |

The five training kitchens have been named as Advanced, Basic, Bulk, Demonstration and Satellite kitchen. Table 1 provides the details of equipment installed in each kitchen as well as what students learn. Altogether, students will prepare 32 sets of Indian, Nepali and Continental dishes from their first to fourth semesters of training in the Advanced and Basic kitchens. In addition, third and fourth-semester students will learn to prepare several types of a la carte menus. Moreover, students learn to prepare 16 different set menus in the Bulk kitchen that are intended to cater to large groups. The Satellite kitchen is complementary to the Basic kitchen and used for reheating purpose. The Demonstration kitchen is used by instructors for the demonstration of a number of theoretical as well as practical aspects. Students also have the chance to sample the dishes prepared during the demonstration by the instructors. Figure 1 shows the workflow process at the Advanced, Basic and Bulk training kitchens.

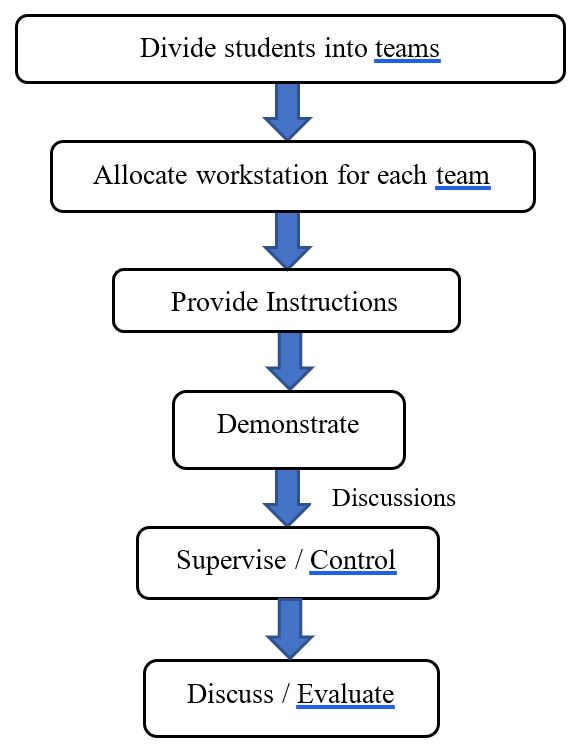

Figure 1: Workflow process at the training kitchens

During the practicum, each cohort of students is divided into several groups of 20 and each group is then assigned to different tasks such dispensing beverages, handling pantry service, preparing food at workstations, taking care of utilities, and performing as a food server, including a cashier and a supervisor. For an entire semester, the same group of 20 students will obtain practical training in all aspects of food and beverage operations. Instructors play important roles, not only by providing training but also by ensuring that students are fully engaged and participate in the entire training process. While preparing food in the Advanced and Basic training kitchens, instructors start a typical day in a kitchen by dividing the 20 students into 10 teams. Since there are 10 workstations with 40 ranges in both kitchens, each team of two students has an opportunity to work with two ranges. While preparing food at the Bulk kitchen, the 20 students are divided into five teams, and each team is assigned a separate task required for bulk food preparation including cutting, food preparation and cleaning, among others.

The training activity that follows revolves around four functions: instructions, demonstration, supervision and control, and discussion and evaluation. In the beginning, instructors provide a brief introduction of the activities that the students need to carry out, the goals for the day, individual team’s job responsibilities, a general procedure of the work to be carried out and what students can and cannot do during their practical session. The instructor then demonstrates the procedure of the kitchen work. Students watch and observe the instructors’ activities and are free to help the instructor and/or ask questions.

After the instructor finishes, each team of students is asked to discuss between themselves in detail, the entire procedure. This part of the training process helps students to clarify and understand the work that they need to carry out for the day. Additionally, it helps them to remember the process, the part of the work they would perform in the team, and the areas where they would need to help each other.

Then, the students repeat the same procedure and prepare the meal which eventually is served in the restaurants. The instructor performs ‘supervision’ and ‘controlling’ functions concurrently as he or she observes students and their work during the entire preparation and cooking session. If a student experiences a problem, the instructor further guides the student to resolve the problem. Since each student is assigned a different job, all students are engaged during a typical practice session. Furthermore, since each student is responsible for completing a certain task, the completion of the overall kitchen task rests on the completion of tasks by all students. Any inappropriate activity by a student including misuse of the equipment is recorded by the instructor and the students are subjected to disciplinary action. Finally, the instructor asks the students to share with each other in their own team, their experiences, problems they faced during the food preparation, and how those problems could be resolved. The instructor then checks and evaluates the work performed by the students before the food is served in the restaurants.

Participatory training approach at the training restaurants at NATHM

While the first and second-semester students undertake their training in training Restaurant I and II, training Restaurant III is mainly used by the students studying in the third and fourth semesters. Table 2 identifies what each student learning in the training restaurants, while Figure 2 illustrates the workflow process int raining restaurants. The students learn three different forms of service in the Training Restaurants I and II: pre-plated service, platter to plate (silver service), and buffet service. Importantly, students learn and extensively practice subtle but important aspects of service such as the way pre-plated (food is prepared in the kitchen on a service plate and is served from the right-hand side of the guests) and platter (food is prepared in the kitchen and portion on a platter and is served from the left-hand side of the guests on a plate using service gears) meals are served.

Table 2: Training Restaurants and their uses at NATHM

| Training restaurants | Students who use the restaurants | What students learn |

| Training Restaurant I & II | First and Second Semesters | Independently manage the food service counter, display food counter according to the menu, provide food services, keep a record of the food consumption (and the guests), pre-planning of services and scene (mise-en-scene), keep a record of pre-service and post-service inventory of service equipment, set up a professional dining room, lay and re-lay table cloths, and set up a table with cutlery, crockery, glassware, table condiments and linen. |

|---|---|---|

| Training Restaurant III | Third and Fourth Semesters | Breakfast services, a la carte menus services, platter to plate (silver) services, room services, banquet services, mixed drinks services, preparing a duty roster, assigning duties to a team and preparing a sales report. |

In Training Restaurant III, students learn and practice more advanced forms of training including personal and specialized services. They also learn to prepare and serve more than thirty varieties of mixed drinks including different types of coffee. Additionally, the students also learn and practice basic administrative tasks from the opening to closing of a restaurant. Towards the end of the semester, students organize a theme lunch event. While training restaurants are not opened to the public for commercial purposes, faculty members and students are allowed to consume meals on a rotating basis. External guests, including high government officials, are also invited to attend state banquet services or to have a casual lunch to appreciate the tasks performed by the students.

While serving at a training restaurant, the group of 20 students is again divided into 10 different teams, and each team is assigned a table where four guests would sit. Therefore, each student has an opportunity to serve two guests. The roles of students while providing service at the restaurants are changed on a rotating basis to ensure that each student has an equal chance of developing all the skills required by a food and beverage server while serving guests sitting in different table arrangements.

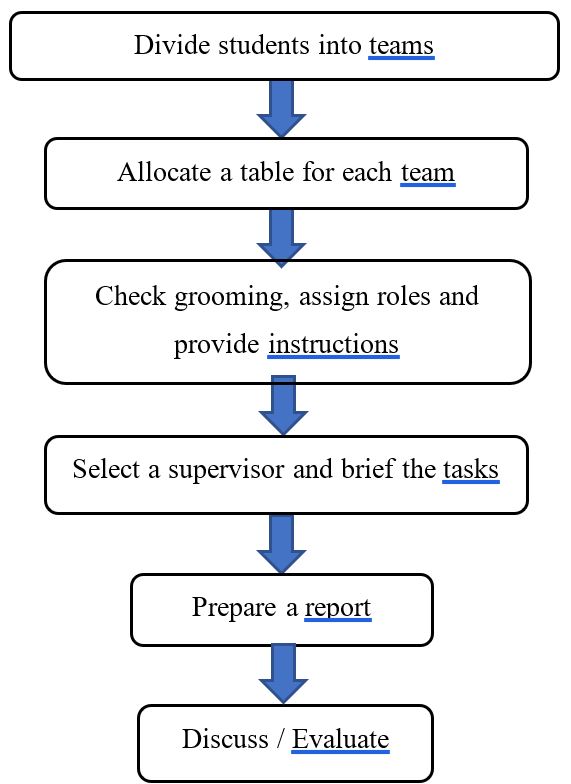

Figure 2: Workflow process at the training restaurants

After checking the status of students’ personal hygiene, grooming and appearance, the instructors allocate students to different wings of the training restaurant including service areas, and cash counter/reception, and assign roles that they need to perform during their practical sessions. The instructors brief them about the menu and the service patterns required for the day (particularly to the servers). The instructor then selects a student as a supervisor who supervises the activities of other students in close coordination with the instructor. The supervisor is also briefed on the individual aspects he/she needs to pay attention to during supervision. In case a student faces a problem or a difficulty in performing his or her duty, the supervisor assists the student to complete the training duty. After the restaurant service has been completed, an operational report for the day is prepared by the supervisor and submitted to the instructor. This report includes details of any problems that students and/or guests faced during and recommendations for further improvement. Finally, the instructor asks all the teams to share their experiences for the day and provide their opinions. A brief discussion on the supervisor’s report is also held to understand the challenges and issues that need to be resolved and ‘good practices’ that can be replicated in the future.

Reflections

Understanding food preparation or providing services in the restaurants requires students to understand/anticipate the implicit/explicit effects of the actions they take which can be generally described through a workflow process. Consequently, most existing hotel management institutions rely heavily on providing training to their students based on workflow process chart, and focus on developing hand-crafted features through a variety of models including both text instructions and cooking images (for example, see Pan et al., 2020). However, it is important to understand that these are non-trivial tasks and mastery of these tasks requires conceptual clarity and a considerable use of common-sense to resolve unforeseen problems. Additionally, the existing food-centric education models that are adopted by many hotel management institutions are mostly intended to help students to pitch attractive career options in the industry (NFCI, 2018). While useful, such an industry-focused approach hinders the creativity of many students as they concentrate solely on developing skills that are widely accepted and practised (Peng et al., 2013).

Creativity is essential in the food business, and as a result, food consumers across the world have been able to consume innovative and exclusive dishes. However, creativity also requires students to think outside the box, immerse in what they do, and analyse the entire process objectively. It is where the participatory approaches of training, such as that provided at NATHM become useful. The approach of participatory training, employed at NATHM encourages student engagement and contribution during a training session and enables them to transfer hands-on experiences to them. Based on their curriculum, the students obtain extensive knowledge and understanding of the ways the equipment is used, and the processes that are generally needed to follow during the entire training session. But at the same time, the students also learn from each other’s experiences and implement them during their own training. Since students work as a team and receive a variety of training together, they develop bonds and personal connections which motivates them to help each other and resolves each other’s problems. Although the training is undertaken as a formal procedure, because of the participatory methods that are used to provide training, student engagement during the training session is high. This approach adopted by NATHM provides an opportunity for students to learn best practice implemented by actual hotels and also equips them with professional knowledge, skills and ideas that they can effectively, efficiently and creatively use in their everyday practices.

While the benefits of participatory approach of providing practical training are immense, it is also not completely free from weaknesses. Since this model of providing training is based on a participatory approach, rather than coaching, the model requires students to develop their ‘thinking patterns’ as professionals. They need to engage in the activities, participate in discussions and provide feedback to overcome challenges and improve overall processes and efficiency. In this regard, the experiences of NATHM demonstrate that one of the key challenges that instructors and students face is related to the psychological adjustment of the students. Since the trainees are undergraduate students, many of them are entirely new to the cooking and/or serving process, and have problems in identifying, holding and using the kitchen equipment or restaurant cutlery. Although the instructors provide them with complete information and demonstrate the entire process before the students begin their actual work, many students expect guidance on each step of the way, just like in the coaching approach. Moreover, the participatory approach being used at NATHM requires the same group of 20 students to work in a kitchen or a restaurant, generally, for the entire day (most theory classes at NATHM are designed in a way that they do not have conflicts with the practical training). The long working hours in practical training not only causes physical fatigue among the students but also sometimes develops intra-team conflicts and/or inter-team rivalries.

It is essential, therefore, for hotel management institutions that aim to employ the participatory approach of providing practical training, to understand the psychological needs of students, considering their age, previous and their motivations to engage in practical training. Often, additional workshops, motivational lectures from industry experts, and industry visits help students to motivate themselves, maintain discipline and focus on their learning goals. In-house counselling services provided by the institutions is also useful to help students develop a positive mindset and cope with stress and other factors that negatively affect them.

Conclusion

A country like Nepal relies heavily on the tourism and hospitality industry for its economic development. Institutions such as NATHM play a key role in providing qualified future staff. While the value of theoretical knowledge is immense in understanding the ways the tourism and hospitality industry operates, hands-on experience provided through practical training by hotel management institutions is paramount in managing daily operations of tourism and hospitality establishments, particularly hotels. However, it is equally important to ensure that such practical training incorporates components that are based on real-life activities in which students get involved and obtain knowledge and information that is valuable for them. A participatory training approach, such as the one used by NATHM, equips students with skills and knowledge required by the industry, and helps them to develop their own creativity. Indeed, such approaches need consistent monitoring of the psychological needs of the students, as well as motivating them using a variety of methods.

References

Alexander, M. (2007). Reflecting on changes in operational training in UK hospitality management degree programmes. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 19(3), 211-220.

Higher Education Funding Council for England. (1998). Review of Hospitality Management. Higher Education Funding Council for England.

ILO. (2018). The enabling environment for sustainable enterprises in Nepal International Labour Organization, ILO Country Office for Nepal.

LeBruto, S. M., & Murray, K. T. (1994). The Educational Value of” Captive Hotels”. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 35(4), 72-79.

MOCTCA. (2019). Nepal Tourism Statistics 2018. Government of Nepal, Ministry of Culture, Tourism & Civil Aviation.

NFCI. (2018). Industry. https://www.nfcihospitality.com/

Pan, L.-M., Chen, J., Wu, J., Liu, S., Ngo, C.-W., Kan, M.-Y., Jiang, Y., & Chua, T.-S. (2020). Multi-modal Cooking Workflow Construction for Food Recipes. Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Multimedia.

Peng, K.-L., Lin, M.-C., & Baum, T. (2013). The constructing model of culinary creativity: an approach of mixed methods. Quality & Quantity, 47(5), 2687-2707

Thapa, B., & Panta, S. K. (2019). Situation Analysis of Tourism and Hospitality Management Education in Nepal. In C. Liu & H. Schänzel (Eds.), Tourism Education and Asia (pp. 49-62). Springer.