67 Destination Image Analytics

Estela Marine-Roig

Since Kevin Lynch’s pioneering work on the image of the city (Lynch, 1960), researchers have devoted significant attention to analysing tourist destination images (TDI) because they are a determining factor when choosing where to vacation. Most of the authors used the surveys as data sources to analyse the perceived TDI. Marine-Roig (2010) claimed travel blogs as objects of study for the perceived image of a destination. She developed this line of research during her doctorate (Marine-Roig, 2014b) by including travel blogs and online travel reviews (OTR) in the sources of user-generated content (UGC). Among the milestones of the research line, the following contributions stand out.

1. Theoretical

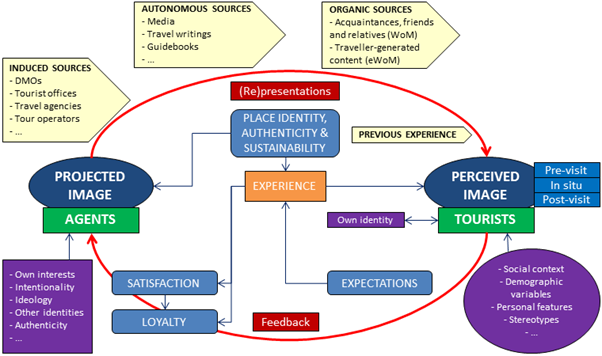

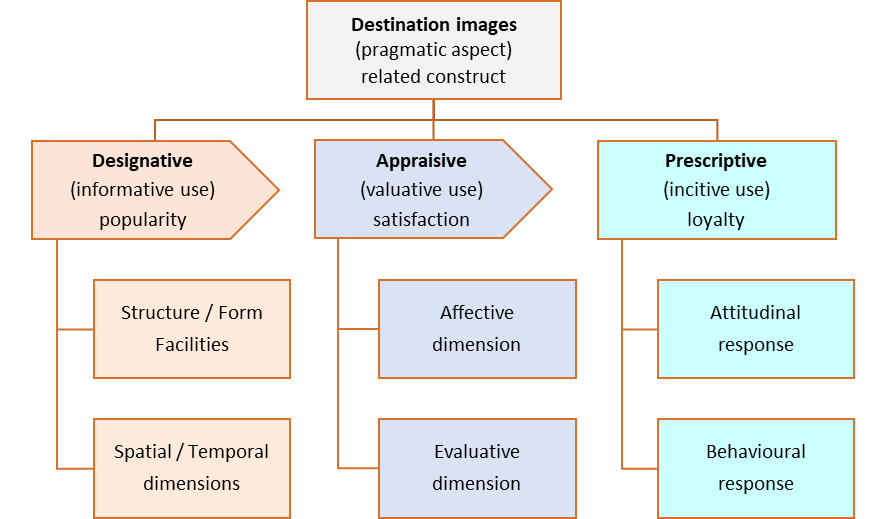

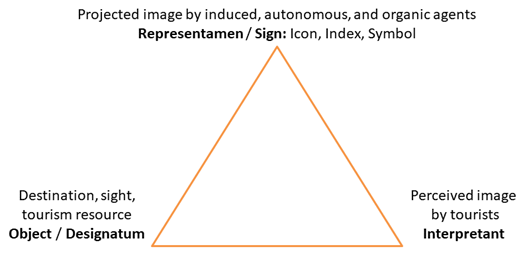

In addition to the PhD thesis (Marine-Roig, 2014b), a study (Marine-Roig, 2015a) highlighted the role of identity and authenticity in the construction of TDI and represented a holistic framework of TDI formation through a circular diagram (Figure 1). Currently, she addresses as a data source traveller-generated content (TGC) defined as narratives, opinions and ratings shared on social media and based on the visitor’s experiences of travelling, sightseeing, entertainment, shopping, lodging and dining in a tourist destination (Marine-Roig & Huertas, 2020). In addition, she introduced semiotic aspects of TDIs into the conceptual framework (Marine-Roig, 2021) as an element of discussion (Figure 2). She later coined the term “destination image semiotics” (Marine-Roig, 2024) to represent the close relationship between Peirce’s semiotic triad, Morris’s semiotic trichotomies and the TDI construction circle (Figure 3).

1.1 Destination image formation circle

The image of a town is a multidimensional and complex construct. The image of a pleasure travel destination is a global concept (gestalt). It is a holistic construct that, to a greater or lesser extent, derives from attitudes regarding the perception of the destination’s tourist attributes and resources. The most frequent core words in TDI definitions (Lai & Li, 2016), such as “impression”, “perception”, “belief” and “idea”, confirm the subjectivity of the perceived TDI. From this subjective perspective, the TDI is a mental representation of the destination’s resources.

In Figure 1, one can observe agents, constructs, information sources, and major variables involved in the construction of the image. These elements are interrelated in a circle. At opposite points of their diameter, agents project the image and tourists perceive. The perceived image may vary according to the stage of the trip (before, during and after). The representations of the tourist destination are in the arc Agents-Tourists and the opinions of visitors (feedback) are in the arc Tourists-Agents. The visitor’s lived experience is in the centre of the circle. Furthermore, in Figure 1, one can observe some of the variables that explain the subjectivity of the image perceived by tourists and discordance of representations in the projected image by the agents. Next, the most important aspects of the scheme are explained.

- Information sources. The representations come from two sources of information: primary and secondary. Secondary sources are grouped into three types: induced, autonomous and organic (Gartner, 1993; Marine-Roig & Ferrer-Rosell, 2018). In the organic sources of Gartner, the TGC propagated through electronic word-of-mouth (eWoM) has been added and previous experience has been segregated. The latter is distinguished by being a primary source and enjoying the highest credibility for tourists since it is based on information personally acquired in a previous trip to the area.

- Expectations. The lived experience has as antecedent expectations that the tourist internalized previously. In the pre-visit phase, the image is a set of expectations and perceptions a prospective traveller has about a destination. There are often discrepancies between projected and perceived images. These can be grouped under two concepts (Marine-Roig & Ferrer-Rosell, 2018): discordance in the representations, when promoters distort reality to suit their interests that may not be coincident, and incongruity in the image when the projected image does not match the current perception of tourists. The contrast between positive image and negative reality often leads to disappointment or anger upon arrival, and false images restrict the learning potential of travel, one of its most valuable and enduring foundations. The greater the difference between image and reality, that is, between expectation and experience, the more likely it is that tourists will be dissatisfied. For example, when the image perceived in advance is positive and the reality perceived in situ is negative, there is a negative incongruity causing a great dislike.

- Place sustainability. Destination competitiveness is illusory without sustainability. From this perspective, the expression “sustainable competitiveness” is tautological. At the same time, one of the most influential researches in the scientific literature on tourism stated (Buhalis, 2000): “Interestingly, the sustainability of local resources becomes one of the most important elements of destination image, as a growing section of the market is not prepared to tolerate over-developed tourism destinations and diverts to more environmentally advanced regions” (p. 101). From another perspective, tourists’ perception affects brand image sustainability.

- Place identity and authenticity. Identity and authenticity are part of the projected image, but can also directly influence the experience through existential authenticity (oriented activity or experienced authenticity). There is a relationship between image, authenticity, identity and place attachment.

- Satisfaction and loyalty. Perceived image through experience is a forerunner of tourist satisfaction and loyalty. At the same time, satisfaction is also an antecedent of loyalty. In tourism, loyalty is measured by intentions of future behaviour, specifically by the tourist’s predisposition (attitude) to return to the place or recommend it both through WoM and eWoM. Satisfaction and loyalty have their negative side when they become dissatisfaction and disloyalty. Many authors have demonstrated these relationships. In addition, satisfaction and loyalty are placed on the path that goes from the tourist to the agents, because overall satisfaction positively affects image and loyalty in all models.

1.2 Semiotic aspects of destination images

The American philosopher and semiotician Charles William Morris proposed semiotics as the science of all signs to include non-linguistic and even nonhuman sign processes, and defined semiotics as syntactics, semantics and pragmatics and their interrelationships (Posner, 1987). Syntactics covers relationships between signs, including the rules of the sign system; semantics covers the meaning of the sign in relation to its object; and pragmatics refers to the origin, use, and effects of signs. Syntactics is not included in the scope of the present study. Semantics is divided into three aspects: designative, appraisive and prescriptive, but these three modalities of signification can co-occur. Finally, pragmatics comprises three uses: informative, valuative and incitive. As can be seen in Figure 2, there is a hierarchical relationship between the three aspects: tourists must have information to evaluate the destination or its tourist resources; in turn, this valuation is necessary for repeat visit intentions and for recommending or discouraging a visit to prospective tourists.

Figure 2 shows an adaptation of the semiotic trichotomies of Morris, developed from the model of Pocock and Hudson (Morris, 1946; Pocock & Hudson, 1978), with the addition of facilities and temporal dimension to the designative aspect, and the subdivision of the prescriptive aspect in behavioural and attitudinal responses.

- Facilities. Next to the structure and form that characterize physical image, concept has added facilities that cover the relatively abstract mental image (Lynch, 1960) of a tourist resource. The visitor identifies a structure such as a museum, aquarium, spa, hotel, restaurant, or other services related to tourism. Not all authors have considered that services are attributes of the image. However, in one of the most influential papers in the scientific literature on TDI (Beerli & Martín, 2004), infrastructure and activities (hotels, restaurants, bars, transport, excursions, etc.) are considered as determining dimensions or attributes of the perceived TDI.

- Temporal dimension. The image is built and changes over time. For example, a Mediterranean seafront does not have the same image in summer as it does in winter; similarly, the image of Japan is different in the season of flowering cherry trees compared to the rest of the year.

- Prescriptive response. The prescriptive response has been specified, dividing it into behavioural and attitudinal responses to analyse the tourist’s intentions and actions.

The model allows measuring three constructs related to TDI using TGC as a data source: (1) the informative use of the designative aspect allows deducing the popularity of a given tourist resource. Popularity depends on the number of posts referring to the resource located in time and place; (2) the evaluative use of the appraisal aspect, in its affective and evaluative dimensions, is useful for measuring visitor satisfaction; and (3) the incitive use of the prescriptive aspect serves to measure visitor loyalty, both the attitudinal and behavioural intentions of visitors.

1.3 Destination image semiotics

Scholars attribute the founding of modern semiotics to the American philosopher and semiotician Charles Sanders Peirce (Oehler, 1987). According to this author, Peirce’s reflections start from a simple notion: a sign is something that represents something else and is understood by someone, or has a meaning for someone. From it, Peirce’s triad of sign-object-interpretant is deduced. Regarding the relationships between signs and objects, Peirce divides signs into: (1) icons that have a resemblance to the object, e.g., a picture, a diagram; (2) indices that relate in some real way to the object, e.g., a signpost, the symptom of an illness; and (3) symbols that have no similarity or physical connection to the object, e.g., a flag, a swastika. These sign categories are not mutually exclusive.

For the purposes of this study, although Peirce’s triad is useful to substantiate the relationships between the image projected by the agents, the tourism resource and the image perceived by tourists (Figure 3), there are two issues related to the interpretant that need further explanation and development: How does the visitor value the information (right side of the triangle) in contrast to his or her experience (base of the triangle)? and What is the visitor’s behaviour? The semiotic trichotomies of Morris, who argued for the resolution of the problems posed by the sign-behaviour relationship (Morris, 1946), help answer these questions. This semiotician was clear that all human action is unthinkable without processing and evaluating signs, just as Peirce stated that all thought is in signs (Oehler, 1987; Posner, 1987). Both considerations lead to the universal applicability of semiotics.

2. Methodological

(1) A first methodological article presented a webometric formula to select the most suitable online data source for a case study (Marine-Roig, 2014a); (2) methods for selecting, downloading, arranging, and debugging tourist data from websites were presented (Marine-Roig & Anton Clavé, 2016a); (3) methods for analysing multiscale TDIs through spatial coefficients (Marine-Roig & Anton Clavé, 2016e) were examined; (4) methods for extracting information from OTR paratextual elements (Marine-Roig, 2017b) and HyperText Markup Language (HTML) meta-tags were described (Marine-Roig, 2017a); and (5) methods for analysing the content of OTRs were detailed (Marine-Roig, 2022b, 2022a).

3. Empirical

The main topics analysed through case studies and TGC were as follows: smart tourism (Marine-Roig & Anton Clavé, 2015); religious tourism (Marine-Roig, 2015b, 2016); sentiment analysis (Marine-Roig & Anton Clavé, 2016b); pull factors (Marine-Roig & Anton Clavé, 2016d); gap between projected and perceived TDIs (Marine-Roig & Anton Clavé, 2016c; Marine-Roig & Ferrer-Rosell, 2018); territorial tourist brands (Marine-Roig & Mariné Gallisà, 2018); social media events (Marine-Roig et al., 2017, 2020); sightseeing, lodging and dining experiences (Marine-Roig, 2019); gastronomic image (Marine-Roig et al., 2019, 2024); personal safety (Marine-Roig & Huertas, 2020); satisfaction and loyalty (Marine-Roig, 2021; Marine-Roig et al., 2022); accommodation (Marine-Roig, Daries, et al., 2023); serious leisure (Marine-Roig, Lin, et al., 2023); and destination image semiotics (Marine-Roig, 2025).

3.1 Experiential marketing

As a corresponding author (Lalicic et al., 2021; Lin et al., 2022), she applied her TDI framework (Marine-Roig, 2019, 2021) to address the co-design or co-creation of tourist experiences, as well as studying the role of semiotics in environmental awareness campaigns (Vallverdu-Gordi & Marine-Roig, 2023).

3.2 Main findings

In a case study of peer-to-peer accommodation (753,366 OTRs) in Barcelona’s districts (Marine-Roig, 2021), results showed that accommodation location significantly determined the OTR narrative and confirmed the exaggerated positivity of Airbnb’s OTR scores.

In another case study of upscale hospitality services (317,979 OTRs) in Asia and Europe (Marine-Roig, 2024), results showed that three-star restaurants and five-star hotels were more popular in terms of the number of OTRs, but diners and guests were more satisfied at and loyal to two-star restaurants and four-star hotels. This big data finding contradicted previous survey-based research on quality services.

Acknowledgement

The author is grateful for the funding received from the Spanish Ministries through the projects: Assessment of the effects of changes in the Spanish tourist model over mature coastal resorts (LITORALTUR) [Grant ID: SEJ2005-05677]; Territorial innovation and development models in coastal tourist destinations. Analysis at different spatial scales (INNOVATUR) [Grant ID: CSO2008-01699]; Tourism, residential mobility and territorial competitiveness. Local responses to dynamics of global change (GLOBALTUR) [Grant ID: CSO2011-23004]; Use and influence of social media and communication 2.0 in tourism decision making and destination brand image. Useful applications for Spanish tourist destinations (COMTUR2.0) [Grant ID: CSO2012-34824]; The transformative effects of global mobility patterns in tourism destination evolution (MOVETUR) [Grant ID: CSO2014-51785-R]; Tourism analysis of peer-to-peer accommodation platforms in Spanish destinations through user-generated content and other online sources (TURCOLAB) [Grant ID: ECO2017-88984-R]; Revaluation of destinations through the semiotic aspects of the gastronomic image and the content generated by tourists (GASTROTUR) [Grant ID: TUR-RETOS2022-017]; and Analysis of the effects of audio-visual fiction on tourist destinations and tourist experiences (ADYTUR) [Grant ID: PID2023-147875NB-I00].

Written by Estela Marine-Roig, University of Lleida (UdL) and Open University of Catalonia (UOC), Spain

Read Estela’s letter to future generations of tourism researchers

References

Beerli, A., & Martín, J. D. (2004). Factors influencing destination image. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(3), 657–681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2004.01.010

Buhalis, D. (2000). Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tourism Management, 21(1), 97–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(99)00095-3

Gartner, W. C. (1993). Image formation process. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 2(2–3), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v02n02_12

Lai, K., & Li, X. (2016). Tourism destination image: Conceptual problems and definitional solutions. Journal of Travel Research, 55(8), 1065–1080. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287515619693

Lalicic, L., Marine-Roig, E., Ferrer-Rosell, B., & Martin-Fuentes, E. (2021). Destination image analytics for tourism design: An approach through Airbnb reviews. Annals of Tourism Research, 86, article 103100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.103100

Lin, M. P., Marine-Roig, E., & Llonch-Molina, N. (2022). Gastronomic experience (co)creation: evidence from Taiwan and Catalonia. Tourism Recreation Research, 47(3), 277–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2021.1948718

Lynch, K. (1960). The image of the city. The MIT Press.

Marine-Roig, E. (2010). Los “Travel Blogs” como objetos de estudio de la imagen percibida de un destino [Travel blogs as objects of study of the perceived destination image]. In A. J. Guevara Plaza, A. Aguayo Maldonado, & J. L. Caro Herrero (Eds.), Turismo y Tecnologías de la Información y las Comunicaciones (pp. 61–76). Facultad de Turismo.

Marine-Roig, E. (2014a). A webometric analysis of travel blogs and review hosting: The case of Catalonia. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 31(3), 381–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2013.877413

Marine-Roig, E. (2014b). From the projected to the transmitted image: the 2.0 construction of tourist destination image and identity in Catalonia [Rovira i Virgili University]. https://hdl.handle.net/10803/135006

Marine-Roig, E. (2015a). Identity and authenticity in destination image construction. Anatolia: An International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research, 26(4), 574–587. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2015.1040814

Marine-Roig, E. (2015b). Religious tourism versus secular pilgrimage : The basilica of La Sagrada Família. International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage, 3(1), 25–37. https://doi.org/10.21427/D7KM6Z

Marine-Roig, E. (2016). The impact of the consecration of “La Sagrada Familia” basilica in Barcelona by Pope Benedict XVI. International Journal of Tourism Anthropology, 5(1–2), 95–115. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTA.2016.076776

Marine-Roig, E. (2017a). Measuring destination image through travel reviews in search engines. Sustainability, 9(8), article 1425. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9081425

Marine-Roig, E. (2017b). Online travel reviews: A massive paratextual analysis. In Z. Xiang & D. R. Fesenmaier (Eds.), Analytics in Smart Tourism design: Concepts and methods (pp. 179–202). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-44263-1_11

Marine-Roig, E. (2019). Destination image analytics through traveller-generated content. Sustainability, 11(12), article 3392. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123392

Marine-Roig, E. (2021). Measuring online destination image, satisfaction, and loyalty: Evidence from Barcelona districts. Tourism and Hospitality, 2(1), 62–78. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp2010004

Marine-Roig, E. (2022a). Analytics in hospitality and tourism: Online travel reviews. In C. Cobanoglu, S. Dogan, K. Berezina, & G. Collins (Eds.), Advances in Hospitality and Tourism Information Technology (pp. 1–25). University of South Florida M3 Publishing. https://doi.org/10.5038/9781732127586

Marine-Roig, E. (2022b). Content analysis of online travel reviews. In Z. Xiang, M. Fuchs, U. Gretzel, & W. Höpken (Eds.), Handbook of e-tourism (pp. 557–582). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-05324-6_31-1

Marine-Roig, E. (2024). Destination image semiotics: Evidence from Asian and European upscale hospitality services. Tourism and Hospitality, 5(2), 472–488. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp5020029

Marine-Roig, E. (2025). Comparing online gastronomic images through customer reviews: Evidence from Asia, Europe, and the USA. In M. H. Bilgin, D. Hakan, E. Demir, & Z. Cséfalvay (Eds.), Eurasian Studies in Business and Economics Perspectives (pp. 189–207). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-80256-0_12

Marine-Roig, E., & Anton Clavé, S. (2015). Tourism analytics with massive user-generated content: A case study of Barcelona. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 4(3), 162–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.06.004

Marine-Roig, E., & Anton Clavé, S. (2016a). A detailed method for destination image analysis using user-generated content. Information Technology & Tourism, 15(4), 341–364. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-015-0040-1

Marine-Roig, E., & Anton Clavé, S. (2016b). Affective component of the destination image: A computerised analysis. In M. Kozak & N. Kozak (Eds.), Destination marketing: An international perspective (pp. 49–58). Routledge.

Marine-Roig, E., & Anton Clavé, S. (2016c). Destination image gaps between official tourism websites and user-generated content. In A. Inversini & R. Schegg (Eds.), Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2016 (pp. 253–265). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28231-2_19

Marine-Roig, E., & Anton Clavé, S. (2016d). Semi-automatic content analysis of trip diaries: pull factors to Catalonia. In M. Kozak & N. Kozak (Eds.), Tourist behaviour: an international perspective (pp. 46–55). CABI. https://doi.org/10.1079/9781780648125.0046

Marine-Roig, E., & Anton Clavé, S. (2016e). Perceived image specialisation in multiscalar tourism destinations. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 5(3), 202–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.12.007

Marine-Roig, E., Daries, N., Cristobal-Fransi, E., & Sánchez-García, J. (2024). The role of upscale restaurants in destination image formation: a semiotic perspective on gastronomy tourism. British Food Journal, 126(12), 4147–4162. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-04-2024-0416

Marine-Roig, E., Daries, N., Martin-Fuentes, E., & Ferrer-Rosell, B. (2023). Where you sleep tells what you care about. In B. Ferrer-Rosell, D. Massimo, & K. Berezina (Eds.), Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism (pp. 166–171). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-25752-0_19

Marine-Roig, E., & Ferrer-Rosell, B. (2018). Measuring the gap between projected and perceived destination images of Catalonia using compositional analysis. Tourism Management, 68, 236–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.03.020

Marine-Roig, E., Ferrer-Rosell, B., Daries, N., & Cristobal-Fransi, E. (2019). Measuring gastronomic image online. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(23), article 4631. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16234631

Marine-Roig, E., Ferrer-Rosell, B., & Martín-Fuentes, E. (2022). La construcción de la imagen del destino en Internet: El caso de la Comunidad Valenciana [Destination image construction on Internet: Case of the Valencian Country]. Espejo de Monografías de Comunicación Social, 2022(6), 215–242. https://doi.org/10.52495/c8.emcs.6.p88

Marine-Roig, E., & Huertas, A. (2020). How safety affects destination image projected through online travel reviews. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 18, article 100469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100469

Marine-Roig, E., Lin, M.-P., & Llonch-Molina, N. (2023). Cooking classes as destination image contribution: a serious leisure perspective. Leisure Sciences, in press. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2023.2253806

Marine-Roig, E., & Mariné Gallisà, E. (2018). Imatge de Catalunya percebuda per turistes angloparlants i castellanoparlants [Image of Catalonia perceived by English-speaking and Spanish-speaking tourists]. Documents d’Anàlisi Geogràfica, 64(2), 219–245. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/dag.429

Marine-Roig, E., Martin-Fuentes, E., & Daries-Ramon, N. (2017). User-generated social media events in tourism. Sustainability, 9(12), article 2250. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122250

Marine-Roig, E., Martin-Fuentes, E., & Daries-Ramón, N. (2020). User-generated events in tourism: A new must-not-miss phenomenon. In V. V. Cuffy, F. Bakas, & W. J. L. Coetzee (Eds.), Events tourism: Critical insights and contemporary perspectives (pp. 47–69). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429344268-6

Morris, C. W. (1946). Signs, language and behavior. Prentice-Hall.

Oehler, K. (1987). An outline of Peirce’s semiotics. In M. Krampen, K. Oehler, R. Posner, T. A. Sebeok, & T. von Uexküll (Eds.), Classics of Semiotics (pp. 1–21). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-9700-8_1

Pocock, D., & Hudson, R. (1978). Images of the urban environment. Macmillan.

Posner, R. (1987). Charles Morris and the behavioral foundations of semiotics. In M. Krampen, K. Oehler, R. Posner, T. A. Sebeok, & T. von Uexküll (Eds.), Classics of Semiotics (pp. 23–57). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-9700-8_2

Vallverdu-Gordi, M., & Marine-Roig, E. (2023). The role of graphic design semiotics in environmental awareness campaigns. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), article 4299. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054299