37 TOURISM DESTINATION IMAGE – Contributions by Statia Elliot

To walk in another’s shoes

stroll far streets

hear music and language

feel climate

shop, eat, worship

experience another world

and discover me.

I wrote this poem while working on my PhD, living for a year in Hill’s View Villa, Seoul. Born and raised in Canada, to be surrounded by a foreign culture and immersed in image theory, inspired my thesis, A Comparative Analysis of Tourism Destination Image and Product-Country Image (Elliot, 2007). My goal was to advance place image theory through research that combined knowledge from the two fields of marketing that dealt most extensively with place image: Tourism Destination Image (TDI) – the effects of beliefs, ideas, and impressions that a person has of a destination; and Product-Country Image (PCI) – the effects of “place” image on buyer attitudes toward products from various origins. Although the focus of both fields is the influence of place image on consumer behaviour, each had developed independently of the other, and notwithstanding their common object of interest, there had been no systematic research that fully combined the two perspectives. I set out to undertake the first ever in-depth cross-fertilization of ideas between these two significant fields of research, to break down silos.

Developing the first integrated model of place image

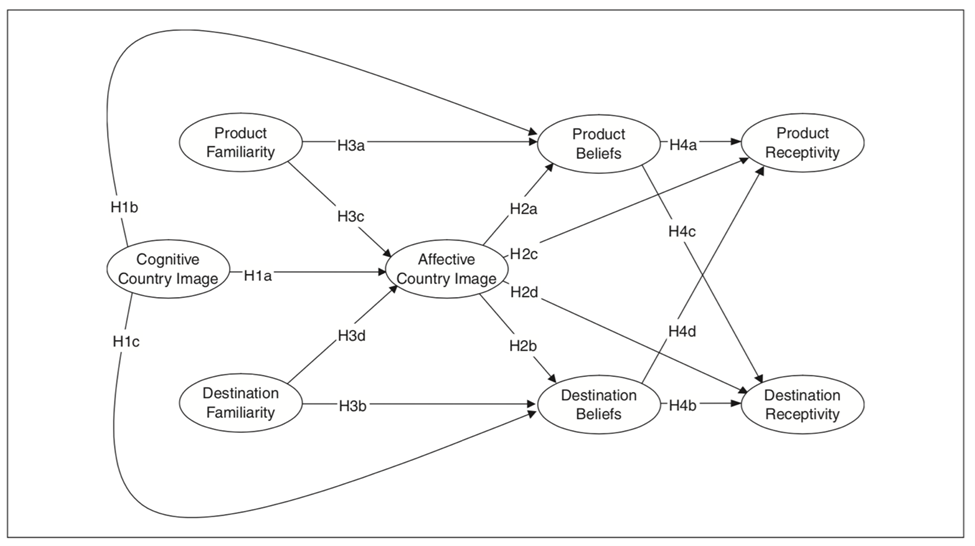

To explore relationships between cognitive and affective dimensions of place, and tourism and product beliefs and behaviours, I developed a theoretical model by merging research and knowledge from both tourism and product-country fields. The resulting Integrated Model of Place Image (IMPI) incorporates a mix of TDI and PCI image measures, comprising eight constructs and 26 variables, as a framework for the analysis of any place of interest (Figure 1).

I first tested my IMPI model using consumer survey data from South Korea to compare image measures of two countries, the U.S. and Japan (Elliot, Papadopoulos & Kim, 2011), further expanded (Elliot & Papadopoulos, 2016) with data from Canada and two more target countries, in a 2×4 analysis using Structural Equation Modeling. The results revealed that cognitive country image had greater influence on product factors, affective country image had greater influence on destination factors, and familiarity only influenced product beliefs and behaviours. Of greatest interest to me, consumer beliefs exhibited a strong cross-over effect, particularly in the direction from product beliefs to destination receptivity. In other words, a consumer who is familiar with a country’s products and positively evaluates that country’s products will be more receptive to the idea of travelling there. The influence of destination beliefs on receptivity to a country’s products, though weaker, was also evident. The study not only revealed how the general country, product, and tourism components of country images were related, but also what image emerged for each country. For example, Canada’s natural beauty and good-natured people stood out, combined with high consumer evaluations for positive attributes, such as safe and trustworthy, to form an image of a true, strong, and free country – though free of products it might seem. While associations to Canada’s abundant natural resources were strong, there was a lack of knowledge of Canadian products, and relatively low evaluations for built tourism (e.g., accommodations).

The uniqueness of each country was further supported in a related study of Australia’s image from the perspective of Canadians and South Koreans (Elliot, Papadopoulos & Szamosi, 2013). For Australia, it is the kangaroo, Sydney, and the Australian people that combine with high consumer evaluations for pleasant, ideal, friendly, and appealing scenery attributes to form an image of a strong tourism destination. Australia’s affective measures (e.g., pleasant) were rated higher than the cognitive measures (e.g., technology), and its Destination Beliefs (e.g., scenery) were higher than its Product Beliefs (e.g., innovativeness). The cross-country assessment of the IMPI in this study generally supported the main postulates of past research that country image influences beliefs, which influence receptivity. It also supported the significant influence of Affective Country Image directly on Product and Destination Receptivity – while at the same time there were key differences in the paths on the product and tourism sides. Unlike the first application of the IMPI to the USA and Japan (Elliot et al., 2011) which found the product paths to be stronger than the tourism paths, the findings of the Australia study found the tourism paths to have greater influence. Moreover, the cross-over effect, a key strength of IMPI testing, was influential from Product Beliefs to Destination Receptivity but not from Destination Beliefs to Product Receptivity for the USA and Japan – yet the results for Australia were the contrary, with influence from Destination Beliefs to Product Receptivity and not the reverse. These differences indicate that the IMPI relationships are driven by the individual strengths and weakness of each country and suggest that consideration of both a country’s tourism and product images is necessary to advance the overall effectiveness of place branding.

Identifying an “ambassador effect” across products and destinations

In 2017, De Nicso, Papadopoulos and Elliot further extended place image research, finding the presence of an “ambassador effect” that had not been studied in TDI or PCI research: a satisfied international tourist who may be both an enhanced consumer but also, once back at his or her place of origin, a “welcome ambassador” not only for the tourism industry of a place but also for the place’s products. Products are routinely exported for consumers to build familiarity toward a country through goods that are available to consume without venturing away from home. The study was the first to assess how visiting experience affects post-visit consumption intentions towards the country’s products. Notably, product beliefs also affected destination beliefs, as tourists familiar with the country’s products use product beliefs to infer evaluations of it as a tourism destination, reinforcing their post-visit behavioural intentions. This important finding extends to the tourism realm the “summary” model explanation (Han, 1989) from PCI research – and buttresses the argument that views of a country’s products can and do serve to colour its perceived image not only as producer but also in terms of other capabilities. Furthermore, the results indicate that a satisfactory tourism experience can not only affect expected loyalty and positive word-of-mouth towards a destination, but also can play a significant role in influencing post-visit intentions towards the nation’s products. Thus, the presence of an “ambassador effect” is revealed suggesting a powerful path from satisfied international tourist to destination ambassador for both travel to a place and for the place’s products.

Extending TDI to the Most Influential Tourism Brand model

While place image is an important factor in destination choice, it is not the only influencer, yet tourism research so often focuses on one concept in isolation from others. Once again breaking silos, Elliot, Khazaei and Durand (2016) extended the measurement of brand influence to include hotels, attractions, airlines, travel agents as well as city, state, and country destinations: 100 brands in one study to represent the mix that is tourism. Applying the first-ever Most Influential Tourism Brand (MITB) model, nine dimensions were found to influence brand preference most, with the degree of influence varying by product category. Country brands were most influenced by the virtual dream dimension as potential travelers explore destinations online, provincial/state brands were more influenced by the trust factor of the comfort zone and corporate citizen dimensions, and at the city level, influential brands were influenced by the big shot and bold dimensions.

Calling for more cross fertilization of research fields

Today’s consumer shops the global market almost as commonly as today’s researcher references it. Globality is reality. My corner grocer offers a broad range of foreign products from African spices and Asian vegetables to European soup mixes and South American nuts. Further, the Covid-19 pandemic has increased our time online where we find the world’s music, movies, and news as casually as we click. This expansive exposure creates innumerable associations in the consumer’s mind to create a metamorphic image of place.

The Integrated Model of Place Image (Elliot et al, 2011, 2016) breaks down the silos between research of product, place and destination image to reveal a cross-over effect from product beliefs to destination receptivity and from destination beliefs to product receptivity. A satisfied international traveler can become an ambassador not just for a favored destination, but for that place’s products, a “halo effect” that has potential to extend beyond the evaluation of products based on their country’s image (Han, 1989) to encompass the influence of tourism destination image on product beliefs and vice versa. Further, when multi-products were measured simultaneously in the Most Influential Tourism Brand model (Elliot et al, 2016), different levels of place were found to have different attributes of strength. Potential travelers were most influenced by the Virtual Dream of countries, the Comfort or trust of a state, and the Big, Bold reputation of a city destination.

In practise, countries from Iceland to New Zealand and parts between have attempted to build holistic place brands, calling for more research to understand how a place’s tourism and product images interact in the minds of target consumers across the globe. By the very nature of image, a multi-dimensional complex concept, more cross fertilization between research fields will help to advance our understanding of its powerful influence.

Written by Statia Elliot, Universiity of Guelph, Canada

References

De Nisco, A., Papadopoulos, N., & Elliot, S. (2017). From international travelling consumer to place ambassador: Connecting place image to tourism satisfactions and post-visit Intentions. International Marketing Review, 34(3), 425-443.

Elliot, S., & Papadopoulos, N. (2016). Of products and tourism destinations: An integrative, cross-national study of place image. Journal of Business Research, 69, 1157-1165.

Elliot, S., Khazaei, A., & Durand, L. (2016). Measuring dimensions of brand influence for tourism products and places. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 10(4), 1-27.

Elliot, S., Papadopoulos, N., & Szamosi, L. (2013). Studying place image: An interdisciplinary and holistic approach. Anatolia: An International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research, 24(1), 5-16.

Elliot, S., Papadopoulos, N., & Kim, S. (2011). An integrated model of place image: Exploring tourism destination image and product-country image relationships. Journal of Travel Research, 50(5), 520-534.

Elliot, S. (2007). A comparative analysis of tourism destination image and product-country image. Management Dissertation. Carleton University, Canada. https://doi.org/10.22215/etd/2008-06695.

Han (1989). Country image: halo or summary construct? Journal of Marketing Research, 26(2), 222-229.