84 GENDER STUDIES – Contributions by Helena Reis

After working in Tourism for many years, I decided to go back teaching at the University. For that, I had to complete a Master’s Degree. So I chose Women’s Studies and, for my dissertation, I decided to make use of my practice in tourism. Then, I found my life was written in the books…

1) Male-dominated culture of the organisations: Glass Ceilings and Sticky Floors

Organisations in society are frequently male dominated structures (Kanter, 1979; 1997), entire departments where the work is assured by women: receptions/front desks; restaurants/administrative/accountings, but where the person “in charge”, “responsible for” is always a man, often less qualified, with less studies or experience than the women he is leading, getting a better wage and perks (Hultin and Szulkin, 1999; Reis and Correia, 2013b). Often these men occupy the position because “women are not natural leaders, they are not fit for leading” (Reis, 2000).

What I learnt at the master’s in Women’s Studies made me understand what had puzzled me along the 16 years I worked in tourism. The more I studied, the more clearly I could identify the male-dominated cultures of the organisations I had worked for: The Casinos of Algarve, where the presence of women was restricted to the reception and housekeeping; you would not find any women in the Gambling rooms, Slot machine rooms, restaurants, bars or even in the kitchen. No wonder that my entrance as a Public Relations (PRs) in the 1980s, with a lot more power over some departments than PRs have today, was so difficult to accept, I was seen as a “huge intrusion”. By definition, the Casinos are very private worlds with rules of their own, but things have changed and now-a-days you can find various female PRs – the great difference is that, I could take decisions, introduce changes, and give orders to several departments, as long as I showed positive results. Today, teams of female PRs are normally under a male manager, who owns the power of decision.

Still in the 1980s, I worked for a British tour operator (T.O.) with one of the largest operations in the Algarve; this T.O. worked in a close relationship with many hotels. The functioning of these hotels unveiled another reality that has been researched and confirmed over and over again: the Glass Ceiling1 paradigm (Moore and Buttner, 1997, among many) – according to the Oxford English Dictionary, in the American Magazine World/Adweek, March 15, 1984: “Women have reached a certain point – I call it the glass ceiling. They’re in the top of middle management and they’re stopping and getting stuck.” (http://womeninpower.org.au). In those hotels, women could be find as middle managers but not as top. More commonly, they would help their direct boss, not defying him, in order to maintain what could be considered a privileged job (Reis, 2000).

This metaphor complies with another aspect that affects even more women in the workplace: the Sticky Floor2, that was common practice in those days and, unfortunately, still is two decades later. The ‘sticky floor’ (…) is described as a situation arising where otherwise identical men and women might be appointed to the same pay scale or rank, but the women are appointed at the bottom and men further up the scale. The term ‘sticky floor’ was coined in 1992 by Catherine Berheide in a report for the Centre for Women in Government. (http://womeninpower.org.au)

2) Beyond our reach: homophily networking, mentoring protectionism

And when I finally went to work for the oldest and biggest travel agency in Portugal, (in the 1990s) with branches all over the world, I could witness and confirm further barriers women face in the workplace: speaking several languages was a great advantage in tourism and often paid extra for each language. When I entered the agency, I was immediately told that, even though I could speak French and my direct chief could not, I would not get any extra payment and, in fact, my business card would say “Assistant Sales Manager”, even if we both had exactly the same tasks and responsibilities. Soon I understood the invisible but imperative male networking engrained in the informal culture of the company (Ibarra, 1992; 1993; Krackhardt and Hanson, 1993): in those days, tourism was a very dynamic activity, changing and adapting day-by-day, so many vital decisions were taken after working hours, while discussing problems, ideas, over a drink at the nearest bar. Naturally, only men had time to attend these informal meetings, since women were always overburden with what is known as the ethics-of-care (looking after the others’ needs before one’s own); the double-day/double-shift – household responsibilities, family, often also the husband’s family (Reis and Correia, 2013b; 2013c). Family obligations are deeply related to making time for oneself and women are the most constrained, as men do not allow “paid work or familiar obligations to compromise golf participation” (McGinnis and Gentry, 2006: 230). Another informal benefit in career progression was the mentoring-relationship, which is so common now-a-days but not at that time, since only men seemed to be familiar with this strategy and knew how to use it. The friendship with a well-positioned superior showed to be a great reward in times of promotions. Of course these relations of power (Dowding, 1996) implied making favours but it was a fair price to pay … all this, gave men a great advantage over their female colleagues and, when promotion opportunities arose, men were much better positioned (Ibarra, 1992; 1993; Krackhardt and Hanson, 1993; Reis, 2000).

So, having lived and witnessed all this, when time came for me to write the dissertation, (1999/2000) I did not hesitate to expose discriminatory patterns and traditions that men easily controlled. So I thought…

I concentrated my research on the low number of women occupying top management positions. My dissertation is entitled (2000): Empreender no Feminino – Estratégias e percursos de mulheres em Agências de Viagens no Algarve”, a study about the travel agencies in the Algarve.

I found there were 106 agencies operating in this region, and only six were run by women. From these six, two were the owners of the agencies. They had been working for many years in different companies, knew all about it and got tired of waiting for a promotion that never came, tired of “knocking on Heavens door” (Bob Dylan, 1973) as one said, so they decided to bang the door and create a place where they could match any men, results would depend on their own leadership (Krackhardt & Porter, 1985). This complies to what Mintzberg (1983;1987) describes as Exit, Voice and Loyalty attitudes. The scenery has changed considerably, as we know, but these two agencies run by women, still operate in the region, due to the sense of adaptation and diversification the owners managed to imprint in their dynamics.

3) My conclusions rocked my convictions

While working for this agency, I witnessed the performances of several knowledgeable, determined women, who could easily run the company and be great mangers, so I assumed they were stuck in these middle management positions due to strong discriminatory patterns. Therefore, these women seemed to be the perfect group to confirm the impediments women face in the career ladder. Yet, the interviews proved otherwise:

The second group did not seem to be aware of the prejudice of gender bias, or, at least, they accepted and even agreed that men were more “capable” of imposing power on their peers, so it was normal and correct that they occupied the top positions without any resistance from qualified women. They did not think of challenging men; it was easier to let things be as they were. In fact, two women were regional managers of the agencies, but during the interviews, I realized and they confirmed, that all the decisions were now made in Lisbon, at the headquarters and by men, so the real power had shifted, meaning that, when a woman reaches a top position regionally, the decision power moves further, like walking in an escalator but never reaching the top.

A third group was even more surprising: these women admitted that, although they were absolutely sure of their capacities for managing a company, to run the agencies, this would imply so many changes in their personal lives, that they were not willing to accept it: working late hours, weekends, handling personalities within the agency, balancing internal controversies.

I had to concede that, after all, it is not always the men’s fault.

13 Years Later …

… I had the opportunity to deepen my studies on gender, under the supervision of the well acknowledged tourism researcher, Professor Antónia Correia, at the University of Algarve. She transformed my vague and limited idea into a PhD thesis entitled: Gender asymmetries in Golf Participation: tradition or discrimination? (Reis, 2013a), which is composed by a series of 7 articles published in journals/books. Together we entered one of the last “for-gentlemen-only” bastions: the exclusive world of golf. Her vison of how research should contribute to the enhancement of knowledge, catapulted my work to the international level.

Golf was introduced in Portugal and in many other countries by the British and with it, came the male hegemony of interdicting women to enter the club houses. The great challenge was to understand why do women choose to participate in a leisure activity that has excluded them for centuries.

To better contextualise the history of repeated patterns, we created a framework of narratives of 25 life stories of famous Anglo-American women who excelled in golf in a highly discriminatory era (19th and 20th centuries), the pioneers that felt the discrimination in a direct and rough way. A historical ethnographic approach to analyse their stories (Reis and Correia, 2016a).

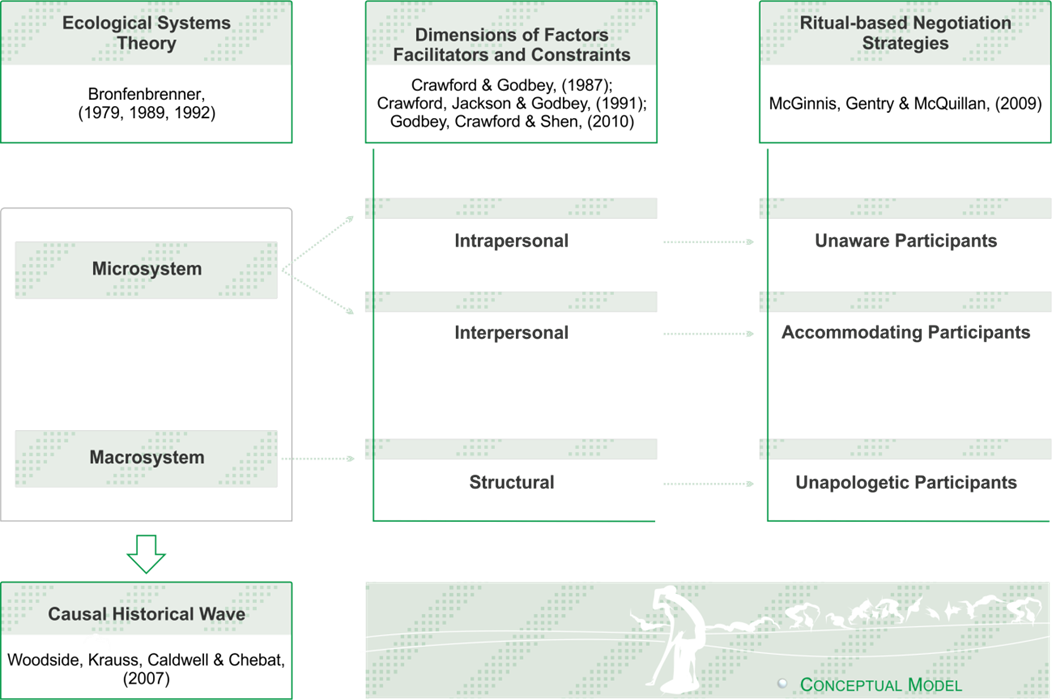

Departing from there, we grounded our study on several theories that explain how the women’s’ environments can influence their choices in life (see table 1). The 3 dimension of factors paradigm – intrapersonal, interpersonal and structural – functioning and facilitators or inhibitors to participation in leisure activities, sports in general, was crucial (Reis and Correia, 2013b; Reis and Correia, 2014). Our work displays great heterogeneity in golf participation, since there are groups who play professionally, others that enjoy playing in mixed competitions, men and women, and finally a group known as “social golfers” that enjoy playing with female friends and just for the fun (Reis and Correia, 2013d).

Results

The exhaustive study of these factors provided a deep comprehension of different types of attitudes women take when facing male dominated environments and, furthermore, strategies they use to cope with the obstacles these environments rise. It was possible to identify and confirm strategies McGinnis, Gentry and McQuillan (2009) advanced in their study: (a) “accommodating,” meaning that some women recognize masculine rituals and work around them; (b) “unapologetic,” referring to the ones that challenge male rituals attempting to create female inclusive alternatives; (c) “remaining unaware,” those who focus on golf as a sport and ignore/refuse its masculine hegemony (McGinnis et al., 2009: 19). The larger group of social golfers were very clear in their analysis: the majority of them are aware of the burdens imposed on women with the “double day” / ethics of care” that penalise women’s participation in any kind of leisure activities, but they are not willing to introduce major changes in their lives – they agree with slow and not drastic shifting of roles (Reis, Correia and McGinnis, 2016b).

Conclusion

The tendency to blame men for all the gender asymmetries in career progression or participation in activities that are still considered male bastions has to be re-evaluated. According to our conclusions, there are various perspectives we have to consider: 1) despite the barriers, many women have succeeded and can be found in top positions in the organisations, politics, academia; their performance reveals how crucial the female contribution is; 2) yet, many others opt for not disputing these positions with men and prefer to remain at middle management or in positions that allow them room for manoeuvre, may it be the family or socialising with their peers.

Our findings indicate that a large number of women are aware of their capacity and skills for going further, but they choose not to. They prefer to adapt and change only in what may favour them. Additionally, also a large number do not even seem to acknowledge more elusive/invisible discriminatory patterns, feeling comfortable with the way things are and not willing to change them.

My contribution to the gender studies research is that, after more than 20 years studying and researching, we have to be careful with generalized ideas about discriminatory patterns imposed by men/male dominated corporations; the border between the trivial opinion and scientific data is very thin.

The more we study gender issues, the better women will understand how to deal/cope with patterns that have existed for centuries and favour men. By exposing my conclusions – which, far from just blaming men highlight that many women prefer not to confront the status quo – more women will understand they are not alone in their decision, whatever it may be: strategies used by women to face gender prejudice range from confrontation to being unaware or accommodating.

Disclosing these strategies is crucial, since it provides information and guidelines for other women, who may believe “there is no way out” to certain situations where they feel trapped.

Written by Helena Reis, University of Algarve, Portugal

Read Helena’s letter to future generations of tourism researchers

References

Dowding, K. (1996), Power, Open University Press, Buckingham, UK. http://womeninpower.org.au accessed 24.06.2021

Hultin, M. & Szulkin, R. (1999), Wages and unequal access to organizational power: an empirical test of gender discrimination, Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(3), 453-472.

Ibarra, H. (1992), Homophily and differential returns: sex differences in network structure and access in an advertising firm, Administrative Science Quarterly, 37(3), 422-447.

Ibarra, H. (1993), Personal networks of women and minorities in management: a conceptual framework, Administrative Science Quarterly, 18(1), 56-86.

Kanter, R.M. (1979), Men and women of the corporation, Basic Books, New York.

Kanter, R.M. (1997), Restoring people to the heart of the organization of the future, in (eds) Frances Hesselbein; Marshal Goldsmith; Richrad Bechard, The organization of the future, The peter Drucker Foundation for Nonprofit Management, Jossey Bass Publishers, San Francisco, pp. 139-149.

Krackhardt, D. & Porter, L.W. (1985) When friends leave: a structural analysis of the realtionship between turnover and stayer’s attitudes, Administrative Science Quarterly, 30(2), 242-261.

Krackhardt, D. & Hanson, J. (1993), Informal networks: the company behind the chart, Harvard Business Review, 104-111.

McGinnis, L., Gentry, J. & McQuillan, J. (2009) Ritual-based Behavior that Reinforces Hegemonic Masculinity in Golf: Variations in Women Golfers’ Responses. Leisure Sciences, 31 (1), 19–36.

Mintzberg, H. (1983), Power in and around organizations, ed. Prentice-Hall.

Mintzberg, H. (1987), The power game and the players, in Shafritz, J. & Ott, J.S., Classcis of organization theory, ed. Dorsey Press.

Moore, D.P. & Buttner, E.H. (1997), Women entrepreneurs – moving beyond the glass ceiling, Sage Publications, USA.

Reis, H. (2013a) Gender Asymmetries in Golf Participation: tradition or discrimination? PhD Thesis, University of Algarve.

Reis, H. & Correia, A. (2013b). Gender Asymmetries in Golf Participation, Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 22 (1), 67-91.

Reis, H. & Correia, A. (2013c). Gender Inequalities in Golf: A Consented Exclusion?, International Journal of Culture, Tourism, and Hospitality Research, 7 (4), 324-339, Scopus (SJR -SCImago Journal Rank indicator 0.11).

Reis, H. & Correia, A. (2013d) Gender in Golf: Heterogeneity in Women’s Participation, in Kozak, M., (Ed.) Aspects of Tourist Behaviour, Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Reis, H. & Correia, A. (2014). Facilitators and Constraints in the Participation of Women in Golf: Portugal, in Woodside, A. e Kozak, M. (Eds.). Tourists’ Perceptions and Assessments (Advances in Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, Volume 8), Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp.137-146, DOI: 10.1108/S1871-317320140000008011 (Permanent URL).

Reis, H. and Correia, A. (2016a), Revisiting Life Stories of Famous Women Golfers, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 14 (1), 27-40.

Reis, H. (2000), Empreender no Feminino – Estratégias e percursos de mulheres em Agências de Viagens no Algarve, Universidade Aberta, Lisboa, unpublished.

Reis, H., Correia, A. & McGinnis, L. (2016b). Women’s Strategies in Golf: Portuguese Golf Professionals – Tourist Behaviour: An International (Eds) Kozak, M. Kozak, N. Cabi, UK. ISBN-13: 978 1 78064 812 5.