50 Adventure and Psychological Well-Being

Susan Houge Mackenzie

Following the river: Exploring a journey to and through tourism academia

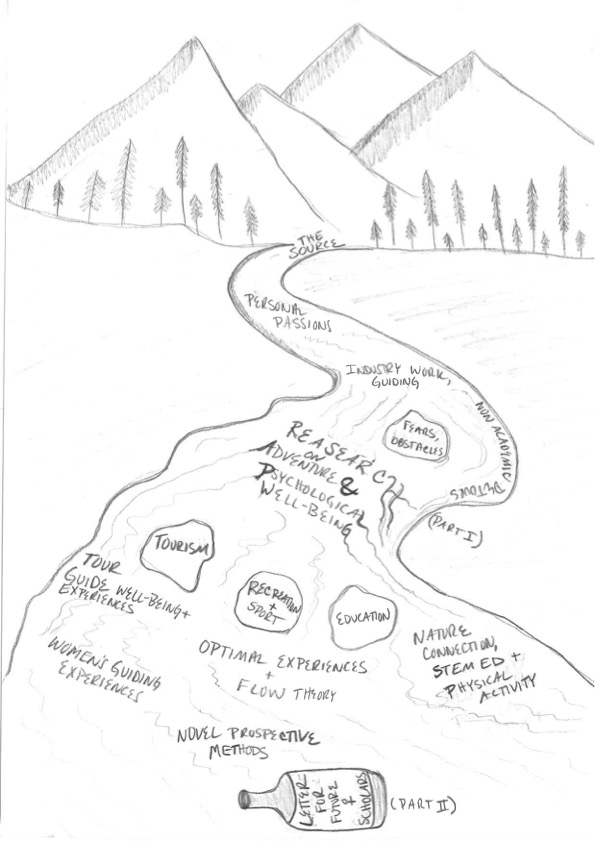

Preface. When I think about how I began my academic journey, I often think of a river. Not a metaphorical river, although I’ll explain below why I think this is apt, but an actual river in Aotearoa New Zealand where I worked as a riversurfing guide for many years. As this publication affords a level of creativity that is often unavailable in academia, and asks authors to tell their personal and academic stories, this chapter uses a literal and metaphorical river to interweave these narratives. The river represents the dynamic, uncertain, challenging, and rewarding nature of the academic path, as well as illustrating the various tributaries and channels that have characterised my academic journey. Hopefully this preface and visual helps to connect the themes within this chapter and in its sister chapter (Letters to future women tourism scholars). Finally, please be kind in your judgement – I’m not a storyteller and if I had my time over, drawing lessons would be at the top of my to do list!

The source. I was born and raised in Minneapolis and was always interested in reading and sports – normally the kind only boys played. But, perhaps as a result of parents who were adamant that gender should not dictate life choices (e.g., my yellow birth announcement read “It’s a person!”), this did not bother me. In fact, looking back I think I must have enjoyed challenging people’s perceptions by playing stereotypically masculine sports, like rugby and (American) football, alongside stereotypically feminine sports such as figure skating. While I tried everything from badminton to unicycling, football (soccer) has been my lifelong sporting love. Even now, surprisingly, football remains a reliable source of physical and mental well-being in the face of life’s many unexpected hardships. Arguably, playing this sport has influenced my life course more than any academic aspirations. It led me overseas, to meet my partner, and to my academic mentor and career.

Midwestern values such as “work first, play second” coupled with perfectionist tendencies created a strong motivation to achieve in sport and education when I was young. I completed a demanding International Baccalaureate high school degree followed by graduating summa cum laude with an undergraduate degree from a rigorous psychology programme. Please don’t mistake these lines for hubris; rather, I write this as a cautionary tale. By the time I finished university, I was completely burned out by American cultural pressures focused on external measures of success, such as income or educational status, which relentlessly demanded ‘more, more, more’ of everything.

To escape the high-pressure pathways I saw looming, I turned down further study at Cambridge and took up an invitation to play football in Australia with a New Zealand stopover. Once I had a taste of the Kiwi way of life, the stopover never really stopped. I backpacked, volunteered on organic farms, and ended up in Queenstown, the self-styled ‘home of adventure’. This is where I discovered the literal river.

The river. On the Kawarau river in Queenstown, I discovered an activity I had never heard of: whitewater riversurfing. While riversurfing was one of the scariest things I had done in my life, and many days ended in tears, something about this novel activity, the visceral immersion in nature, and the guiding lifestyle hooked me. I still can’t say what kept me going in those early days – maybe I simply wanted to prove the head of the all-male staff wrong. After my first training course, he said I would “never be a guide”, and I agreed with him – even years after I started guiding. However, the camaraderie, the profound peace of the natural environment, and the sheer immediacy of this intense activity that downed out external concerns, kept me coming back to that river for many years.

Guiding on the Kawarau river, and later others in Colorado and Chile, fundamentally shaped my academic path. The experiences of complete absorption; learning to manage intense emotions and navigate and enjoy whitewater; becoming a guide; working with culturally diverse guides and clients; and eventually training other guides and shaping industry practices underpin my research in both theoretical and practical terms. These experiences, coupled with on-going engagement in football, led me to incredible mentors who helped me identify how to combine my passions for nature-based adventure, sport, well-being, psychology and intellectual inquiry.

Downstream ripples: Contributions to knowledge. Like the consistent ‘main flow’ (central current) of a river, pervading themes related to adventure and psychological well-being are central to my research. However, this main flow has meandered and manifested in diverse ways across research projects, applications, and outputs, just as rivers have channels that continually separate and reconverge based on changing environments. My primary contributions to knowledge have been in relation to expanding traditional risk-focused models of adventure, challenging how flow theory conceptualises optimal experiences, and proposing predictive models of adventure that can be used to promote well-being in tourism and education contexts. This work seeks to illustrate how adventure scholarship and practices can become more inclusive, to more widely support public well-being (e.g., for recreationalists, students, tourists, guides, communities), and has been accompanied by best practice recommendations for adventure tourism operators, educators, and government agencies. Below, I briefly discuss my key contributions across these research strands in terms of both theory and practice.

Optimal experiences & flow theory

This line of research asks questions such as: How do optimal flow experiences unfold in adventure contexts? How can this help us facilitate well-being in tourism and recreation?

In the psychological literature, the term flow was coined to capture an intrinsically rewarding optimal psychological state characterised by total absorption in an activity and a high sense of control, often in challenging situations. In lay terms, this is often called ‘being in the zone’. Flow has been extensively investigated in sport, exercise, and business contexts, and has been associated with optimal performance and experience, increased motivation, and long-term engagement in an activity (e.g., Csikszentmihalyi, 1990; Jackman et al., 2019; Jackson et al., 2001). Flow has long been conceptualised as a singular optimal state, however our research in suggests that flow experiences are multi-phasic and dynamic, and that participants experience multiple flow states during adventure experiences (e.g., Houge, Hodge, & Boyes, 2010a, 2010b; Houge Mackenzie, Hodge, & Boyes, 2011, 2013). In relation to tourism, the identification of distinct flow states, such as telic flow (serious, outcome-oriented) versus paratelic flow (playful, process-oriented), has important implications for how we structure client experiences, how we train and retain tour guides, and how we ensure safety in adventure tourism experiences. In adventure recreation contexts, our research suggests that flow is a central feature of participants’ experiences; distinct flow experiences are key motivations for enduring adventure recreation participation; and there appear to be unique stages and antecedents of flow in adventure contexts (e.g., immersion in nature; exercising skills to control and reduce risks) (Boudreau, Houge Mackenzie, & Hodge, 2020).

Tour guide experiences & well-being

This line of research asks questions such as: How can we enhance well-being for tour guides and clients? How do women experience tour guiding?

While research has illustrated the importance of tour guides in visitor experiences and organisational success (i.e., as a means to an often profit-driven end), much less research has explored the well-being and experiences of tour guides as worthwhile end in and of itself. The literature has primarily focused on tour guide ill-being (e.g., emotional labour, stress, burnout; Holyfield & Jonas, 2003; Houge Mackenzie & Kerr, 2013; Sharpe, 2005), and associated mitigation strategies, rather than well-being. However, our research has identified how tour guiding has the potential to facilitate well-being and self-development for both guides and clients (e.g., Houge Mackenzie & Kerr, 2016; Parsons, Houge Mackenzie, & Filep, 2019). Key components of guide well-being include: helping guides create a robust protective frame (Houge Mackenzie & Kerr, 2014); teaching strategies for managing the unique stress, emotions and interpersonal interactions within guiding teams (e.g., Houge Mackenzie & Kerr, 2013a, 2013b); and empowering guides with techniques for co-creating unique experiences focused on integrating hedonic, eudiamonic, and/or spiritual well-being (e.g., Houge Mackenzie & Kerr, 2012a, 2012b, 2016, 2017; Parsons, Houge Mackenzie, & Filep, 2019;

Our most recent empirical work has extended these findings by proposing a conceptual model of psychological well-being for tour guides (Houge Mackenzie & Raymond, 2020). This model links key elements of adventure guide’s experiences (e.g., people, natural environments, distinct adventure activities) with primary (e.g. competence, beneficence, nature connection), secondary (e.g., autonomy, relatedness), and tertiary (e.g., sense of purpose, deep absorption) well-being determinants. While collecting data on guide well-being, we also identified a range of unique challenges and opportunities experienced by women adventure tour guides. These findings highlighted specific ways that gender influenced interactions with clients, co-guides and management, and how these gendered interactions often hindered fulfilment of basic psychological needs for competence, autonomy, and relatedness for women guides. In addition, women guides identified how being perceived as a ‘mother figure’ and the psychological burden of client safety could hinder their well-being (Houge Mackenzie, Boudreau, & Raymond, 2020; Houge Mackenzie & Raymond, 2021). We have recommended a range of practical strategies for how these issues might be addressed by guiding teams, adventure operators, and the adventure industry to enhance guide well-being (e.g., Houge Mackenzie & Raymond, 2020, 2021).

Connecting nature, adventure, education & well-being

This line of research asks questions such as: What role does nature play in promoting well-being in adventure tourism, recreation and education contexts? How can nature-based adventure experiences enhance educational, environmental, and health outcomes? How can we make adventure experiences and benefits more inclusive?

Our findings in this area challenge traditional narratives and popular perceptions of adventure as narrowly driven by thrill, risk and sensation-seeking. This literature, and associated research methodologies, often depict adventure as an exclusive domain occupied predominantly by young, privileged, Western males in the service of hedonic outcomes (e.g., Kerr & Houge Mackenzie, 2020). However, our findings suggest that adventure motives and participants are diverse and multifaceted, and that adventure should be reconceptualised in terms of how it promotes opportunities to experience competence, autonomy, belonging, optimal (flow) experiences, emotion regulation, and connection to the natural world (e.g., reflecting a range of eudaimonic and hedonic outcomes) (e.g., Houge Mackenzie, 2013, 2021; Houge Mackenzie & Hodge, 2020; Houge Mackenzie, Hodge, & Filep, 2021; Kerr & Houge Mackenzie, 2012a, 2012b, 2014). For instance, our work has demonstrated how adventure activities are motivated by a range of eudiamonic outcomes linked to self-development, sense of purpose, and mental health, as well as broader community well-being and eco-centric outcomes (e.g., Brymer & Houge Mackenzie, 2017, 2020; Clough, Houge Mackenzie, Mallabon, & Brymer, 2016). These findings have been translated into recommendations for supporting the well-being of diverse populations and natural environments across the following contexts: supporting tourism host communities (e.g., Brymer & Houge Mackenzie, 2015), enhancing youth engagement in STEM [Science, Technology, Engineering, Math] education (Houge Mackenzie, Son, & Eitel, 2018; Houge Mackenzie, Son, & Hollenhorst, 2014; Son, Houge Mackenzie, & Eitel, 2021; Son, Houge Mackenzie, Eitel & Luvaas, 2017); increasing mainstream physical activity levels (e.g., Jenkins et al., 2021), and valuing our local natural environments and reducing carbon emissions (e.g., Houge Mackenzie & Goodnow, 2020).

Novel prospective methods

My final area of contribution to knowledge has been in relation to exploring emerging methods to better understand tourism experiences as they unfold. One way we have addressed the challenge of prospectively studying tourism experiences has been through the use of head-mounted cameras to stimulate recall in adventure tourism contexts (Houge Mackenzie & Kerr, 2012c). This method has proved to be an effective alternative to retrospective recall methods, which often mask the dynamic nuances of adventure experiences. Using this method has allowed us to propose refined models of flow that are multi-phasic and account for distinct flow states (detailed earlier). In addition, autoethnography has offered a novel means of exploring and understanding psychological experience of adventure guiding and the nuanced dynamics at play in this context (e.g., Houge Mackenzie, 2015; Houge Mackenzie & Kerr, 2012a; 2013a, 2013b). Although we initially encountered resistance when seeking to publish autoethnographical findings, writing in-depth about how we employed an analytical authethnographical approach to both collect and analyse data helped to broaden the scope of methods reflected in the tourism literature, and has informed a number of subsequent autoethnographical studies in similar tourism contexts.

The research collective. There is one final thing I must say about the contributions above. They are not ‘my’ contributions. They are contributions made by diverse teams of thoughtful, rigorous, curious, and hardworking scholars, without whom none of these contributions would have reached fruition. I am so grateful to have been involved in these rewarding collaborations. Much like the river trips I used to lead, every research team and project has been unique, and it is these unique combinations that make research rich, enlightening, productive, and fun. Just as exploring a new river is safer and more effective with a cohesive, supportive guiding team possessing complementary skills and shared goals, so too do explorations of new knowledge flourish under these conditions. In my experience, research is fundamentally a collective activity best conducted by cooperative groups with diverse experiences and expertise. Care for the collective is also vital in river contexts. On the river, shared goals (e.g., the well-being of the group), and particularly ensuring the well-being of the least experienced/most vulnerable group members, trumps individual interest. I cannot unilaterally decide to diverge from the group simply because I want to pursue a more challenging route. Rather, this dynamic environment demands that you put group needs above your own desires and interests and consider the common good at all times. Viewing the river as a research metaphor has much to offer us in terms of how we choose to approach and navigate our respective research journeys.

To conclude, this journey, please go to the sister chapter that offers a message in a bottle for future women tourism scholars.

Written by Susan Houge Mackenzie, University of Otago, New Zealand

Read Susan’s letter to future generations of tourism researchers

References

Boudreau, P., Houge Mackenzie, S., & Hodge, K. (2020). Flow states in adventure recreation: A systematic review and critical thematic synthesis. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 46, 101611.

Brymer, E. & Houge Mackenzie, S. (2017). Psychology and the extreme sport experience. In F. Feletti (Ed.), Science and extreme sport medicine (pp. 3-13). Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Brymer, E. & Houge Mackenzie, S. (2015). The impact of extreme sports on host communities’ psychological growth and development. In Y. Reisinger (Ed.), Transformational Tourism: Host Benefits (pp. 129-140). Oxford, UK: CABI.

Clough, P., Houge Mackenzie, S., Mallabon, L., & Brymer, E. (2016). Adventurous physical activity environments: A mainstream intervention for mental health. Sports Medicine, 46(7), 963-968.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Houge Mackenzie, S. (2021). Emerging psychological well-being frameworks for adventure recreation, education and tourism. In E. Brymer (Ed.) Nature, Physical Activity and Health. Routledge.

Houge Mackenzie, S. (2015). Using emerging methodologies to examine adventure recreation and tourism experiences: A critical analysis. Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, & Leadership, 7(2), 173-179.

Houge Mackenzie, S. (2013). Beyond thrill-seeking: Exploring multiple motives for adventure participation. Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, and Leadership, 5(2), 136-139.

Houge Mackenzie, S., Boudreau, P., & Raymond, E. (2020). Well-being and adventure: The experiences of women tour guides in New Zealand. Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Management, 45, 410-418.

Houge Mackenzie, S., & Brymer, E. (2020). Conceptualizing adventurous nature sport: A positive psychology perspective. Annals of Leisure Research, 23(1), 79-91.

Houge Mackenzie, S. & Hodge, K. (2020). Adventure recreation and subjective well-being: A conceptual framework. Leisure Studies, 39(1) 26-40.

Houge Mackenzie, S., Hodge, K. & Boyes, M. (2011). Expanding the flow model in adventure activities: A reversal theory perspective. Journal of Leisure Research, 43(4), 519-544.

Houge, S., Hodge, K. & Boyes, M. (2010). A positive learning spiral of skill development in high risk recreation: Reversal Theory and flow. Journal of Experiential Education, 32(3), 285-289.

Houge, S., Hodge, K. & Boyes, M. (2010). The phasic nature of flow in high risk recreation. Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, and Leadership, 2(2), 51-54.

Houge Mackenzie, S., Hodge, K., & Filep, S. (2021). How does adventure sport transform well-being? Eudaimonic and hedonic perspectives. Tourism Recreation Research. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2021.1894043

Houge Mackenzie, S. & Goodnow, J. (2020). Adventure in the age of COVID-19: Embracing microadventures and locavism in a post-pandemic world. Leisure Sciences, 1-8.

Houge Mackenzie, S & Kerr, J. H. (2016). Co-creation and experience brokering in guided adventure tours. In S. Filep, J. Laing, and M. Csikszentmihalyi (Eds.), Positive Tourism. New York, NY: Routledge.

Houge Mackenzie, S., & Kerr, J. H. (2014). The psychological experience of river guiding: Exploring the protective frame and implications for guide well-being. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 19(1), 5-27.

Houge Mackenzie, S., & Kerr, J. H. (2013a). Can’t we all just get along? Emotions and the team guiding experience in adventure tourism. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 2(2), 85-93.

Houge Mackenzie, S., & Kerr, J. H. (2013b). Stress and emotions at work: Adventure tourism guiding experiences in South America. Tourism Management, 36, 3-14.

Houge Mackenzie, S., & Kerr, J. H. (2012a). A (mis)guided adventure tourism experience: An autoethnographic analysis of mountaineering in Bolivia. Journal of Sport and Tourism, 17(2), 125-144.

Houge Mackenzie, S., & Kerr, J. H. (2012b). Client experiences in mountaineering tourism and implications for outdoor leaders. Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, and Leadership, 4(2), 112-115.

Houge Mackenzie, S., & Kerr, J. H. (2012c). Head-mounted cameras and stimulated recall in qualitative sport research. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 4(1), 51-61.

Houge Mackenzie, S., & Raymond, E. (2021). Women’s adventure guiding experiences: Challenges and opportunities. In M. Baker, E. Stewart, & N. Carr (Eds.) Leisure Activities in the Outdoors: Learning, Developing, and Challenging. CABI.

Houge Mackenzie, S., & Raymond, E. (2020). A conceptual model of adventure tour guide well-being. Annals of Tourism Research, 84, 102977.

Houge Mackenzie, S., Son, J. S., & Eitel, K. (2018). Using outdoor adventure to enhance intrinsic motivation and engagement in science and physical activity: An exploratory study. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 21, 76-86.

Houge Mackenzie, S., Son, J. S., & Hollenhorst, S. (2014). Unifying psychology and experiential education: Toward an integrated understanding of why it works. Journal of Experiential Education, 37(1), 75-88.

Jackman, P. C., Hawkins, R. M., Crust, L., & Swann, C. (2019). Flow states in exercise: A systematic review. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 45, 1-51.

Jackson, S. A., Thomas, P. R., Marsh, H. W., & Smethurst, C. J. (2001). Relationships between flow, self-concept, psychological skills, and performance. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 13(2), 129-153.

Jenkins, M., Houge Mackenzie, S., Hodge, K., Hargreaves, E. A, Calverley, J., & Lee, C. (2021). Physical activity and psychological well-being during the New Zealand COVID-19 lockdown: Relationships with motivational quality and nature. Frontiers in Psychology, 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2021.637576

Kerr, J. H., & Houge Mackenzie, S. (2020). ‘I don’t want to die. That’s not why I do it at all’: Multifaceted motivation, psychological health, and personal development in BASE jumping. Annals of Leisure Research, 23(2), 223-242.

Kerr, J. H., & Houge Mackenzie, S. (2014). Confidence frames and the mastery of new challenges in the motivation of an expert skydiver. The Sport Psychologist, 28(3), 221-232.

Kerr, J. H. & Houge Mackenzie, S. (2012). Multiple motives for participating in adventure sports. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 13, 649-657.

Son, J. S., Houge Mackenzie, S., & Eitel, K. (2021). Interprofessional collaboration to integrate physical activity and “GreenSTEM” education. In J. H. Hironaka-Juteau & S.V. Lankford (Eds.) Interprofessional Collaboration in Parks, Recreation and Human Services: Theory and Cases, Sagamore-Venture.

Son, J. S., Houge Mackenzie, S., Eitel, K., & Luvaas, E. (2017). Engaging youth in physical activity and STEM subjects through outdoor adventure education. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 20(2), 32-44.