83 Centering the Periphery: Market Linkages, Narrative Justice, and the Rise of Community Tourism in Nepal

Aayusha Prasain and Pushpa Thapa

Introduction

Tourism in Nepal has historically been concentrated in a small number of well-promoted destinations, often sidelining the voices, agency, and meaningful participation of local communities (Nepal, 2007). In the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a global reckoning with how we travel, sparking renewed calls for more responsible and equitable forms of tourism that prioritize the well-being of host communities, whose homes and daily lives form the essence of the destinations we visit (UNWTO, 2021).

In this context, community tourism (CT) has emerged as a compelling alternative to conventional tourism models. Rooted in principles of local ownership, co-creation, and equitable benefit-sharing, CT offers an approach where communities actively lead and manage tourism initiatives. A well-documented example is Thailand’s Community-Based Tourism Institute (CBT-I), which empowers communities through participatory planning, skill-building, and strategic partnerships, ultimately fostering cultural pride and long-term socio-economic gains (CBT-I, 2010). More broadly, CBT encompasses tourism experiences that are embedded in local contexts, offering travelers immersive and respectful engagement with cultural heritage, ecological landscapes, and indigenous knowledge systems (Asker et al., 2010; Goodwin, 2008).

In this article, the terms community tourism and community-based tourism are used interchangeably. While much of the academic literature continues to reference “community-based tourism,” there is a growing shift toward terms such as “community-led tourism,” reflecting an evolution toward deeper community ownership and leadership. At the Community Homestay Network (CHN), we (Aayusha Prasain[1] and Pushpa Thapa[2]) intentionally use the term community tourism to reflect a model that is not only based in communities but truly led and co-owned by them. From our experience, such models are anchored in shared values, local knowledge, and inclusive governance, and they align particularly well with the aspirations of young people. Community tourism has enabled youth to build marketable skills, express their identities, and envision sustainable futures without having to migrate away from their hometowns. Empowered by mobile technology and digital storytelling tools, these youth are helping their communities reach wider audiences and, in doing so, are redefining what it means to participate in Nepal’s tourism economy.

My understanding[3] of tourism has significantly deepened and evolved through my professional experience at the CHN. When I first joined, my understanding of tourism like that of many others was shaped by postcards of Nepal’s towering mountains, lush hills, and flowing rivers. These images, though iconic, left out something essential: the people and communities who live in these landscapes. I had not questioned this absence until I began working closely with local homestay hosts, many of them women, whose everyday lives are intricately connected to the very places that attract travelers. Their stories, their labor, and their cultural knowledge had long been missing from the dominant tourism narrative.

This realization mirrored a broader truth about Nepal’s tourism industry. Despite the country’s long-standing association with tourism, the communities that safeguard its natural and cultural heritage often remain marginalized. These same communities, whose sustainable practices protect the ecosystems and traditions that visitors seek, rarely receive equitable recognition or benefit. For me, this was a turning point. It became clear that for tourism to be truly sustainable, it must center the participation, rights, and voices of those who make these destinations possible.

My role at CHN has deepened this understanding. I have come to see that community tourism must move beyond well-meaning rhetoric to become a genuinely transformative model. It must reject tokenistic inclusion and instead embrace the co-creation of tourism experiences that reflect community aspirations, cultural integrity, and long-term stewardship. Destinations should not be treated as consumable or interchangeable, vulnerable to the same overcrowding and commercialization that have plagued mainstream tourism. Equally important is how these experiences are communicated. Marketing and storytelling must prioritize authenticity and community agency, avoiding narratives that exoticize or commodify.

As scholars have emphasized, sustainable tourism must be rooted in empowerment, participation, and mutual respect if it is to contribute meaningfully to equitable development (Salazar, 2012; Trung, Prakoso, Pradipt, Roychansyah, & Nugraha, 2020). These principles now guide not only how I understand tourism, but how I support communities in reclaiming their place within it.

Data Collection Methods

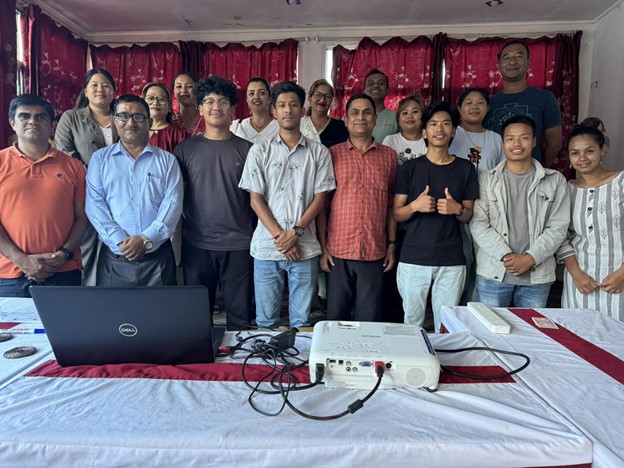

This case study draws on qualitative data collected over a sustained period of engagement with local communities in Nepal. A combination of methods was employed, including direct observation, semi-structured interviews, participatory reflection, and photographic documentation conducted during community visits, coordination activities, and both formal and informal interactions. These methods were complemented by experiential knowledge gained through day-to-day work experiences, ongoing communication with community members, and long-term collaboration with the CHN team. Additional insights were obtained through participation in panel discussions, stakeholder consultations, and knowledge-sharing sessions with a diverse range of actors, including community leaders, local youth, women entrepreneurs, and tourism professionals.

Participants and Timeline

The case is situated within the broader context of CHN’s community tourism initiatives across Nepal. Data collection occurred during multiple phases of engagement; spanning planning, implementation, monitoring, and reflection, between 2021 and 2025. Both authors of this study have been directly involved with CHN since 2021, enabling in-depth and iterative engagement with a wide range of stakeholders. Participants included community members actively involved in tourism activities, wider CHN team, local government representatives, and other individuals and institutions contributing to the advancement of responsible and inclusive tourism models in Nepal.

Ethical Considerations and Limitations

All interviews and personal testimonies presented in this study were conducted with the informed consent of the individuals involved. To ensure accurate and respectful representation, community members whose quotations were included were given the opportunity to review relevant excerpts following the initial drafting of the manuscript. Ethical considerations were central throughout the research process, with care taken to maintain the integrity and agency of participant voices. Nevertheless, some limitations persist, particularly in terms of geographic scope and the granularity of individual narratives, given the diversity of communities and contexts involved. Furthermore, the authors acknowledge their dual roles as practitioner and author of this case study, which may introduce subjective interpretations. These were addressed through triangulation with CHN team debriefings, and community feedback mechanisms to enhance validity and accountability.

Case Description

The transformation of community tourism in Nepal reflects a broader shift toward inclusive, sustainable, and culturally grounded development in rural regions. In response to longstanding challenges such as youth outmigration, limited livelihood opportunities, and gender-based barriers, communities are redefining tourism as a vehicle for empowerment rather than extraction. This shift is evident in places like Dhankuta and Narchyang, where local women and youth are increasingly taking ownership of tourism narratives, creating immersive experiences rooted in cultural authenticity and environmental stewardship. Initiatives such as the HI-GRID project have integrated tourism within broader place-based strategies for climate resilience and social equity, positioning it as a tool to revitalize traditional knowledge and intergenerational collaboration. Within this evolving landscape, the Community Connect initiative plays a catalytic role by strengthening the visibility of these efforts through direct engagement with international travel media and stakeholders. While not the starting point of change, Community Connect enhances global recognition and market access, enabling local narratives to reach broader audiences and positioning communities as co-creators of Nepal’s tourism future. As such, it complements and amplifies grassroots transformations already underway, helping to shift tourism from a peripheral activity to a core strategy for rural development and cultural continuity.

Key Learnings and Community Reflections

Reclaiming Representation and Reconfiguring Power in Tourism

Community tourism in Nepal is undergoing a significant transformation, challenging dominant narratives that have historically framed tourism as an extractive industry designed primarily for external consumption. Such models often prioritize the satisfaction of international visitors while overlooking the agency of local communities. In contrast, a growing movement led by grassroots initiatives is redefining the tourism landscape by emphasizing community agency, cultural self-determination, and inclusive benefit-sharing. These emerging models of responsible tourism do more than diversify Nepal’s tourism offerings; they offer a compelling alternative to conventional approaches by demonstrating what ethical and sustainable travel can look like in practice.

In my journey[4] with the Community Homestay Network, one experience that continues to stand out is our work in Narchyang, a small village nestled along the Annapurna Circuit. In 2019, just before the pandemic disrupted global travel, we welcomed Narchyang into the CHN family, not as a reaction to tourism demand, but as a deliberate intervention. At the time, destinations like Tatopani were facing growing pressure from overtourism, and we saw an opportunity to shift the narrative. Our intention was never to simply divert tourist traffic; it was to reimagine what meaningful travel could look like for both visitors and hosts.

Through the Narchyang Community Homestay, we co-created immersive, community-rooted experiences that honored local culture, landscapes, and livelihoods. What moved me most was seeing community members, especially women, step forward to reclaim their stories and assert their role in shaping how their village is seen by the outside world. For me, this is what responsible tourism is truly about: not just easing pressure on crowded places, but opening up space for lesser-known communities to be seen, heard, and economically included on their own terms.

This reconfiguration of tourism ethics reflects a broader global trend. As solutions advocate and tourism strategist JoAnna Haugen (2023) argues, “Recognizing both the growing demand for more meaningful travel and the need to move away from the typical ‘bucket list’ mentality, many destinations and tour operators are increasingly embracing community tourism, offering travelers deeper cultural connections and more responsible ways to explore.” This shift is also reflected in how responsible tourism in Nepal increasingly centers cultural resilience and values-based development. In Kirtipur, for instance, a women’s collective has reimagined a traditional meal experience, once seen as unpaid domestic labor, into a dignified source of livelihood. Supported by Planeterra, a non-profit organization that uses tourism as a vehicle to uplift communities worldwide, and CHN, this initiative has not only generated income but also fostered a powerful sense of community solidarity. The kitchen, in this case, has become more than an economic asset; it is a space of what feminist scholars call “everyday resistance,” the quiet yet persistent ways in which women challenge structural inequalities through acts of collective care, agency, and redefinition of roles (Kabeer, 1999; Gaventa and Cornwall, 2021). These experiences are invitations into an ongoing socio-cultural dialogue. Contemporary reflections on conscious travel reveal that the search for authenticity has shifted from passive observation to active and ethical engagement with communities. While conventional tourism often reduces culture to a commodity, turning traditions into performances, community tourism in Nepal offers an alternative. It places authenticity in the context of relationships built on trust, mutual respect, and shared meaning. Rather than being spectators, travelers are welcomed as participants in living cultural narratives.

The momo-cooking experience in Kirtipur is more than just an engaging activity for visitors, it has become a platform for women entrepreneurs to build confidence, showcase cultural knowledge, and generate sustainable income. Watching local women lead these sessions with such pride and authenticity reaffirms why experiences like these are vital in responsible tourism. They are not merely economic activities but powerful expressions of agency, identity, and cultural ownership.

As CEO of the Community Homestay Network, my commitment to co-developing such experiences is deeply personal. Growing up as a third culture kid across Asia, from Mongolia to rural Myanmar, I learned early on that home is not defined by geography, but by connection and shared purpose. My parents taught me the value of community and cultural integrity, shaping my belief in tourism as a tool for empowerment, particularly for women whose leadership often sustains local resilience. This is also why partnerships rooted in shared values matter deeply. During a recent exchange, Priyanka Singh, Regional Manager for Planeterra Asia-Pacific, shared, “I couldn’t help but see parallels in your life with mine… no wonder our passion towards our work, family, and travel has made it such a delight working with you and your amazing team at CHN.” Her words reflect the essence of why organizations like CHN and Planeterra remain committed to community-led, women-centered tourism. When values are lived rather than simply stated, they become a driving force for inclusive and lasting change.

Intergenerational and Gender-Responsive Community Tourism in Nepal

In Nepal’s rural regions, youth retention continues to be a critical development challenge, particularly as access to quality education and sustainable employment remains limited. Bhattarai (2025) argues that the persistent outmigration of skilled and educated youth is a direct consequence of systemic barriers in rural education and employment opportunities. Geographic isolation, combined with the accelerating impacts of climate change, has compelled many young people to migrate in search of better opportunities. Traditional livelihoods such as agriculture are increasingly disrupted by climate variability, including reduced water availability and unpredictable growing conditions. These pressures have driven intra- and inter-country migration, eroding traditional knowledge systems and weakening community cohesion (Plan International, 2022; Nepali Times, 2024).

Yet, within this challenging context, community tourism is emerging as a powerful tool for reshaping economic and social futures. By enabling localized, inclusive, and environmentally conscious livelihood opportunities, it motivates both women and youth to remain in their communities while contributing to broader development goals (Acharya, 2023; Panta & Thapa, 2017; UNWTO, 2023).

This shift is reflected in the story of Nabin, a 22-year-old from the Indigenous Aathpahariya community, who has chosen to stay in his village of Khambela rather than migrate. For Nabin and many youth like him, tourism has become a beacon of hope offering a viable path to meaningful employment, cultural preservation, and community development right at home.

Under the HI-GRID project, funded by the Australian Government and implemented by ICIMOD along with collaborative partners[5] tourism has emerged as a promising new livelihood option in the region. It not only offers alternative income opportunities beyond agriculture but also integrates climate solution tools from the outset, ensuring that sustainability and climate resilience are core components of this development approach. In doing so, Nabin has witnessed the journey of Dhankuta from no tourism to gradual onboarding of tourism and its impact. Reflecting on this, Nabin shares, “For the first time, I see tourism not just as business, but as a way to protect our culture and tell our own stories.” He adds with conviction, “Young people like me feel inspired to take charge, not just to welcome visitors, but to shape how our community is seen and understood.” His decision embodies a powerful shift away from cultural tokenism toward cultural authorship, where Indigenous youth actively reclaim and narrate their identities on their own terms (Cultural Survival, 2007). Along with him, his community members feel hopeful for other youths to get inspired with the similar kind of job and stay back in the village taking in their own hand to lessen the migration rate and also take lead on promoting their culture and destination.

As part of my role[6] I feel honored to have contributed to designing and implementing these capacity-building programs, equipping youth with the tools and skills necessary to transition into tourism as a viable livelihood option. From facilitating workshops on climate-smart practices to guiding communities on integrating cultural narratives into tourism, we as a team have worked to ensure that local stakeholders are at the forefront of these transformations. Witnessing Nabin’s journey, from living in a community with no tourism infrastructure to becoming a trained local tour guide, has been one of the most rewarding aspects of this work. He now plays a pivotal role in promoting culturally significant and climate-smart travel experiences, blending traditional knowledge with sustainable practices to safeguard Dhankuta’s rich heritage while addressing the challenges of climate change.

Central to this transformation is not only the engagement of youth like Nabin but also the growing leadership of women entrepreneurs within the community. In Nepal, where women make up roughly half the population, the lack of visible female entrepreneurial role models has long hindered young women’s aspirations (Census Nepal, 2021). Women have historically been underrepresented in entrepreneurial roles due to social norms, mobility constraints, and limited access to resources. Community tourism, however, is disrupting these patterns. Through training and enterprise support, women are not only becoming tourism hosts but assuming leadership roles that challenge long-held gender hierarchies (Acharya, 2023).

Basanti Rana, from the Rana Tharu Community Homestay in far-western Nepal, reflects on this transformation: “We had no experience when we started. Hosting travelers was completely new to us. The biggest challenge was not knowing how it would benefit us or how we could lead and operate something like this as an enterprise. As an Indigenous community, we have often been marginalized in education, economic opportunities, and access to information. I was one of the women who could not even introduce myself before. Today, I am here speaking on a public platform.” Her journey illustrates what scholars describe as “everyday resistance”, where women subtly but persistently reshape social roles through participation, care, and leadership (Kabeer, 1999; Gaventa & Cornwall, 2021).

Such change is not limited to individual women. In Panauti, the first community homestay in CHN’s network, women entrepreneurs have become visible role models, encouraging young girls to take on front-facing and better-paid roles in tourism such as local guiding and bike touring, fields traditionally dominated by men (World Bank, 2017). The intergenerational effect is clear: when younger women see their mothers and neighbors managing enterprises, leading tours, and engaging with guests, they begin to envision new possibilities for themselves.

This dynamic is echoed in the story of Jagmati Tilija, who, inspired by the visible successes in Narchyang, her own community, chose to convert her home’s spare rooms into a homestay instead of migrating. Her decision, like Nabin’s, was shaped by a growing understanding that tourism, when locally led and values-driven can be a viable and empowering alternative to outmigration.

Collectively, these stories point to an evolving model of rural development, one that places culture, care, and climate resilience at its core. Community tourism in Nepal is not just a livelihood strategy; it is a platform for socio-environmental transformation. As youth gain meaningful roles through tourism and women take on entrepreneurial leadership, traditional power structures begin to shift. In doing so, communities cultivate a sense of ownership, pride, and agency that directly counters the forces of marginalization and climate-induced displacement (Panta & Thapa, 2017; Acharya, 2023). Moreover, Ee Ming Toh[7], writing in The Straits Times, urges travelers and tourism professionals to rethink what it means to travel. She encourages a move away from the passive consumption of destinations toward experiences rooted in mutual engagement, shared value, and community-led storytelling. Her encounters in Dhankuta, Panauti, and Janakpur demonstrate how community tourism in Nepal can serve as a powerful vehicle for social inclusion, cultural safe guarding, and sustainable development (Toh, 2024).

Furthermore, as documented in academic literature, the presence of visible, empowered women in public life significantly increases the likelihood that younger generations will pursue non-traditional careers, including entrepreneurship (Hillman, 2024). In this sense, community tourism becomes a space not only of economic opportunity but of gender-responsive, intergenerational learning and transformation.

Positioning Community Tourism in Nepal within the International Market

As someone[8] leading the Community Connect initiative from the Community Homestay Network (CHN), overseeing partnerships and working closely with public relations teams, travel journalists, and tour operators, I often find myself reflecting on the role of passion in community tourism. Passion undoubtedly fuels our work; it brings heart to the co-creation of experiences and anchors our commitment to local empowerment through entrepreneurship. Yet, over the years, I have come to realize that passion alone is not enough. To build a truly entrepreneurial ecosystem within community tourism, we must pair that passion with deliberate strategies around product innovation, long-term sustainability, capacity building, and market integration.

It was with this understanding that CHN conceptualized and launched Community Connect, a collaborative platform designed to bridge the visibility gap between local tourism initiatives and the international travel market. The 2024 edition brought together over 30 international journalists, influencers, and travel professionals to explore emerging destinations such as Dhankuta, Narchyang, Bhada, and Kirtipur. The goal was to not only showcase the richness of these community-led experiences but to position them as viable, compelling alternatives within Nepal’s broader tourism offering. Through our homestay and immersive experiential model, we remain committed to reshaping Nepal’s tourism landscape while fostering authentic cultural exchange and centering community agency and sustainability.

However, promoting off-the-beaten-path destinations is not without its challenges. Travelers often hesitate to venture into unfamiliar regions, and tourism professionals may be reluctant to promote places they have not personally experienced. Community tourism, rooted as it is in lived experience and cultural nuance, cannot be fully captured through brochures or websites. This is why exposure visits, or FAM trips, are essential. They provide the firsthand connection needed to convey the value and integrity of community tourism.

The success of the 2024 edition inspired us to organize Community Connect 2025, a second iteration that welcomed 30 international journalists across various regions of Nepal. Securing their participation was no simple task, nor was it the achievement of CHN alone. It was made possible through a shared vision held by a constellation of partners including Planeterra, HIGRID partners, communications experts like Ms. Casey Mead and Ms. Choy Teh who supported us pro bono, our business collaborators, and most importantly, local governments and communities on the ground. Community Connect stands as a testament to the power of collective action. It demonstrates that when values align across sectors and across borders, community tourism can evolve from a marginal alternative to a recognized pillar of sustainable and inclusive national tourism.

As highlighted by The Tourism Space, familiarization (FAM) trips serve as a vital mechanism for bridging this gap by allowing tourism professionals to experience and understand destinations firsthand, thereby facilitating stronger connections between communities and the wider tourism market (The Tourism Space, 2021). Without strategic marketing, targeted promotion, and international exposure, community tourism risks remaining peripherally appreciated but not integrated within mainstream tourism frameworks (UNWTO, 2023). This disconnect not only limits economic opportunities for communities but also prevents travelers from accessing immersive and meaningful cultural experiences that community tourism offers.

Effective storytelling and narrative ownership are central to overcoming this barrier. As Scheyvens (1999) emphasizes, empowering communities to represent their own identities and experiences is crucial to ensuring tourism contributes to their well-being. Community tourism is inherently experiential, and its value lies in the lived stories and cultural expressions of local populations. Yet, these narratives often remain underrepresented in global tourism discourses due to limited platforms for communities to share their voices.

The Community Connect initiative directly addresses the structural challenges of linking grassroots tourism efforts to global markets by creating meaningful engagement between local communities and international stakeholders. Through carefully designed familiarization (FAM) trips, which bring together travel journalists, tour operators, and media professionals, the initiative facilitates immersive cultural experiences that serve both to promote intercultural exchange and to strategically position community tourism within international tourism circuits. These firsthand interactions not only deepen the understanding of local contexts but also empower communities to share their narratives across global platforms, enabling them to influence the external perception of their destinations (Pax Global Media, 2025). Moreover, Community Connect aligns with key principles of responsible tourism, such as inclusivity, equity, and sustainability (Goodwin, 2011). It goes beyond traditional capacity-building approaches by focusing on visibility, narrative empowerment, and market readiness. Unlike conventional models that stop at infrastructure or skill development, Community Connect bridges the crucial gap between grassroots tourism efforts and international tourism markets. It does so by facilitating cultural exchanges and enabling community members to be active agents in crafting and sharing their tourism experiences.

This approach strengthens the long-term viability of community tourism by enhancing both demand and supply-side readiness. On one hand, international audiences are introduced to authentic, community-led experiences; on the other, communities are equipped to engage with global travelers through storytelling and service delivery. This dual dynamic ensures that community tourism is not just about economic benefit but also about preserving and celebrating intangible cultural heritage (Timothy & Tosun, 2003).

In conclusion, transforming community tourism in Nepal from a niche endeavor to a recognized pillar of the national tourism strategy requires deliberate efforts to enhance global visibility, narrative control, and market connectivity. Initiatives like Community Connect exemplify how structured interventions can bridge these gaps by creating platforms for direct exchange and mutual learning. Through this model, community voices are not only heard but placed at the center of tourism development, contributing to a more equitable and culturally enriched global tourism landscape.

Written by Aayusha Prasain and Pushpa Thapa, Community Homestay Network, Nepal

References

Acharya, B. R. (2023). Community-based tourism for sustainable livelihoods: Case studies from Nepal. Journal of Tourism & Adventure, 7(1), 41–53.

Acharya, S. (2023). Tourism as a tool of women empowerment: A general review. Research Nepal Journal of Development Studies, 6(1), 101–106. https://doi.org/10.3126/rnjds.v6i1.58928

Asker, S., Boronyak, L., Carrard, N., & Paddon, M. (2010). Effective community based tourism: A best practice manual. Sustainable Tourism Cooperative Research Centre.

Bhattarai, R. (2025). Youth migration and structural barriers in rural Nepal: A study of education and employment disconnects. Kathmandu University Journal of Development Studies, 9(1), 45–62.

Boley, B. B., McGehee, N. G., Perdue, R. R., & Long, P. (2014). Empowerment and resident attitudes toward tourism: Strengthening the theoretical foundation through a Weberian lens. Annals of Tourism Research, 49, 33–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2014.08.005

Census Nepal. (2021). National population and housing census 2021. Government of Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics. https://cbs.gov.np/wp-content/upLoads/2022/03/National%20Report.pdf

CHN (Community Homestay Network). (2024). Community Connect 2025: Exposure visit report. Kathmandu, Nepal: CHN Internal Document.

Community-Based Tourism Institute (CBT-I). (2010). Community-based tourism handbook. Bangkok: CBT-I Thailand.

Cultural Survival. (2007). Valuing women as assets to community-based tourism in Nepal. Cultural Survival Quarterly.

Dredge, D., & Jamal, T. (2015). Progress in tourism planning and policy: A post-structural perspective on knowledge production. Tourism Management, 51, 285–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.06.002

Equality in Tourism. (2025). Sun, sand & ceilings: Women in tourism and hospitality boardrooms. Equality in Tourism International. https://www.equalityintourism.org

Gaventa, J., & Cornwall, A. (2021). Power and knowledge: A feminist framework. IDS Bulletin, 52(1).

Gaventa, J., & Cornwall, A. (2021). Power and knowledge: Reimagining the terms of women’s empowerment. IDS Bulletin, 52(4). https://bulletin.ids.ac.uk/index.php/idsbo/article/view/3124

Giri, K., & Darnhofer, I. (2010). Nepali women using community forestry as a platform for social change. Society & Natural Resources, 23(12), 1216–1229. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920903278146

Goodwin, H. (2008). Tourism, local economic development and poverty reduction. Applied Research in Economic Development, 5(3), 55–64.

Goodwin, H. (2011). Taking responsibility for tourism. Goodfellow Publishers.

Haugen, J. (2023). Decolonizing tourism: Community, diversity, nature, and culture. Rooted Storytelling. https://rootedstorytelling.com/rethinking-tourism/decolonizing-tourism-community-diversity-nature-culture/

Hillman, W. (2024). Women and entrepreneurship in Nepal. Journal of Tourism & Adventure, 7(1), 41–53.

ICIMOD. (2020). HI-GRID: Building capabilities for green, climate resilient, and inclusive development in the Lower Koshi River Basin. Kathmandu, Nepal.

Kabeer, N. (1999). Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Development and Change, 30(3), 435–464. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7660.00125

Maharjan, A., Bauer, S., & Knerr, B. (2013). International migration, remittances and subsistence farming: Evidence from Nepal. International Migration, 51, e249–e263. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2012.00789.x

Nepal, S. K. (2007). Tourism and rural settlements: Nepal’s Annapurna region. Annals of Tourism Research, 34(4), 855–875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2007.03.004

Nepali Times. (2024, May 7). Climate crisis, drought, food deficit, migration. Nepali Times. https://nepalitimes.com/here-now/climate-crisis-drought-food-deficit-migration

Panta, S. K., & Thapa, B. (2017). Entrepreneurship and women’s empowerment in ecotourism: A case of community-based homestay in Nepal. Tourism Planning & Development, 14(4), 386–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2016.1243148

Pax Global Media. (2025, June 24). Canadian travel advisor joins delegates at community tourism event in Nepal. https://www.paxnews.com/news/events/canadian-travel-advisor-joins-delegates-community-tourism-event-nepal

Plan International. (2022). Green skills for rural youth: Building capabilities for sustainable livelihoods. https://plan-international.org/uploads/2022/01/green_skills_for_rural_youth.pdf

Pham Hong, L., Ngo, H. T., & Pham, L. T. (2021). Community-based tourism: Opportunities and challenges—A case study in Thanh Ha pottery village, Hoi An city, Vietnam. Cogent Social Sciences, 7(1), Article 1926100. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.1926100

Prasain, A. (2023, March 1). Unfolding Nepalese women’s entrepreneurial journey. Planeterra. https://planeterra.org/unfolding-nepalese-womens-entrepreneurial-journey/

Scheyvens, R. (1999). Ecotourism and the empowerment of local communities. Tourism Management, 20(2), 245–249.

Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. Oxford University Press.

Sharma, P., & Paudel, S. (2023). Unemployment and the skills gap: An analysis of youth labor outcomes in rural Nepal. Journal of South Asian Policy and Development, 6(2), 88–104.

The Tourism Space. (2021, September 15). Why FAM trips are important and what we can learn from other destinations. https://www.thetourismspace.com/blog/fam-trips-important-learn-other-destinations

Timothy, D. J., & Tosun, C. (2003). Appropriate planning for tourism in destination communities: Participation, incremental growth and collaboration. In S. Singh, D. J. Timothy, & R. K. Dowling (Eds.), Tourism in destination communities (pp. 181–204). CABI Publishing.

Toh, E. M. (2024, May 15). The conscious traveller: Stay with locals for a cultural immersion in Nepal. The Straits Times. https://www.straitstimes.com/life/travel/the-conscious-traveller-stay-with-locals-for-a-cultural-immersion-in-nepal

Trung, L. V., Prakoso, A. A., Pradipt, E., Roychansyah, M. S., & Nugraha, B. S. (2020). Community-based tourism: Concepts, opportunities and challenges. Journal of Sustainable Tourism and Entrepreneurship, 2(2), 95–107. https://doi.org/10.35912/joste.v2i2.563

UNWTO & UN Women. (2019). Global report on women in tourism – Second edition. https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2019/11/announcer-second-edition-of-global-report-on-women-in-tourism

World Bank. (2017). Women and tourism: Designing for gender equality. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/401321508245393514/pdf/120477-WP-PUBLIC-Weds-oct-18-9am-ADD-SERIES-36p-IFCWomenandTourismfinal.pdf

World Bank. (2020). Postcard from Sapa, Vietnam: Undoing the damage while seizing the benefits of mass tourism. World Bank Blogs. https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/eastasiapacific/postcard-sapa-vietnam-undoing-damage-while-seizing-benefits-mass-tourism

World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). (2023). How community tourism can support rural development. https://tourism-villages.unwto.org/en/news/how-community-tourism-can-support-rural-development/

The Tourism Space. (2021, September 15). Why FAM trips are important and what we can learn from other destinations. https://www.thetourismspace.com/blog/fam-trips-important-learn-other-destinations

[1] Aayusha Prasain is the CEO of the Community Homestay Network, leading community initiatives that supports the empowerment journey of communities through responsible tourism. With a background in international development, she brings deep experience across grassroots, youth-led, and multilateral platforms, grounded in equity and inclusion.

[2] Pushpa Thapa is the Product Development Lead at Community Homestay Network, where she strengthens community capacities across Nepal and co-designs inclusive tourism experiences. With a background in Travel and Tourism Management, she works with local governments and partners to enhance cultural integrity and experiential excellence in community tourism.

[3] This reflection is based on the experience of Pushpa Thapa, Product Development Lead at the Community Homestay Network.

[4] Based on the experience of Aayusha Prasain, CEO of the Community Homestay Network (CHN), the integration of Narchyang village into CHN in 2019 was a strategic effort to address overtourism in nearby destinations like Tatopani. The initiative promoted immersive, community-based tourism while creating economic and cultural opportunities for local residents. It helped reduce pressure on crowded sites and support more equitable tourism development.

[5] Responsible tourism in Dhankuta is being implemented through the HI-GRID Project, supported by the Australian Government and led by ICIMOD. This initiative is a collaborative effort between Dhankuta Municipality, Chhathar Jorpati Rural Municipality, Community Homestay Network, Smart Paani, and HUSADEC.

[6] This reflection is based on the experience of Pushpa Thapa, Product Development Lead at the Community Homestay Network.

[7] Ee Ming Toh is a Singapore-based freelance journalist and storyteller specializing in travel, social impact, the environment, and culture, with work featured in outlets such as the Associated Press, Al Jazeera, National Geographic, and The Straits Times. In 2024, she was hosted by the Community Homestay Network (CHN) to visit and experience various communities in Nepal, which led to her feature story on community tourism being published in The Straits Times.

[8] This reflection is based on the experience of Aayusha Prasain, Chief Executive Officer at the Community Homestay Network.