84 Consumer Experience

Nina K Prebensen

A story of a research journey: A process approach

Introduction

My academic career started in Alta in 1988. I was hired to help teach tourism students with subjects such as marketing, marketing research, management, and strategy. My master’s degree was within marketing and strategy at the Norwegian Business School in Bergen, Norway. Subsequently, I applied general perspectives of marketing into the empirical field of tourism. The experiential side of tourism (the process of being and doing—during the experience) was lacking in the marketing and management literature.

After some years as an assistant professor, I met and learned from numerous skilled scholars. People like Professor Ning Wang, presenting concepts such as authenticity, encouraged me to study tourism from a psychological perspective.

My PhD, focusing on tourist motivation, was a starting point for appreciating scholars open to new and promising perspectives. And by this I started to acknowledge tourism as more than an empirical field—and more than an industry providing services to a defined market. Following the lead of scholars within the Nordic School of Marketing, i.e., Gummeson, Grönroos, and Strandvik, in addition to scholars proposing new marketing and management logics, i.e., Varo and Lusch, I started to read up on and study “why” and “how” people travel on a tourist journey during their vacation. The concept of value co-creation became captivating. And together with a group of Norwegian scholars, a research submission for the Norwegian Research Council took form. The present paper will tell my story as a researcher within tourism and value co-creation. Hopefully, it will support younger scholars with ideas and ways to structure, put forward, and publish their research. New paths in tourism research are encouraging.

The research project Northern InSights (Opplevelser i nord) took place in Northern Norway over the period 2010–2017. The focus was on value creation and innovation within the tourism industry from the tourist and the firm’s perspectives. As Northern Norway is known to host tourists from all over the world, new knowledge in terms of tourist segments, value creation, and value co-creation was promising.

The aim was to develop a systematic understanding of how sustainable value, that is, experience value for customers and value for firms, is created and co-created between the host and guests, and between the actors with and within the “servicescape”. The project was based on theoretical perspectives such as service-dominant logic, perceived value, sustainability, and cultural differences in consumption.

The research project Northern InSights became a major national and international player in the building of a strong and competitive academic environment that worked in productive collaboration with the tourism industry, offering valuable knowledge for future value creation. The project included three work packages involving 18 defined proposals (single projects).

In close collaboration with tourism enterprises, the project developed a better understanding of the meaning of co-creation and innovation in the tourism industry, and how it leads to new and improved services while also increasing the creation of experience value for the participating actors. The project offered insights into how research can improve value creation in tourism, for both businesses and visitors.

Tourists’ roles and resources in terms of value creation have experienced an increased focus over the last decade. The present paper presents a research journey in exploring, describing, and testing causes and effects of tourist perception of value and their participation in value co-creation processes (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2004). The service-dominant logic (S-D logic) of marketing (Grönroos, 2006; Lusch & Vargo, 2006; Vargo & Lusch, 2004, 2006, 2008) and the perceived value concept (Prebensen, Chen, & Uysal, 2018; Sheth, Newman, & Gross, 1991; Williams & Soutar, 2009) acknowledge the significance of the consumer, i.e., the tourist as an active and partaking actor in value creation and co-creation, and thus the tourist is fundamental for the present research.

Theoretical and empirical perspectives

The theoretical and practical perspectives of marketing management were until the 1970s dominated by consumer goods. In the 1980s and 1990s, the differences between goods marketing and services marketing were explored and the understanding for relationships, networks, and interactions developed. This process of revealing services marketing, as distinct and different from product marketing, put forward four characteristics of services: intangibility, inseparability, heterogeneity, and perishability. However, Vargo and Lusch (2004) argue that the prototypical characteristics identified do not distinguish services from goods and that they only have meaning from a manufacturing perspective. In this line of reasoning, Vargo and Lusch (2004, 2008) suggest a new logic, service-dominant logic, as distinct from product-dominant logic, and put forward the vital differences between services (plural) and service (singular). Services are delineated as either a restricted type of (intangible) good (i.e., as units of output) or an add-on that enhances the value of a good, while service is outlined as a process of doing something for another party—in its own right, without reference to goods—and service is identified as the primary focus of exchange activity. This process of academic discourse gradually laid the ground for the integrated goods/services approach that is now the major question for researchers within tourism and experiences as well as service researchers and practitioners alike.

In the consumer behaviour literature, customer value is delineated as the price paid minus the benefits that the product proposes (Parasuraman, Zeithaml, & Berry, 1985). Within this perspective, the price paid, and the effort put into it, i.e., planning, travelling, helping others, and reading about the destination, are regarded as cost. In experiential consumption, these activities may be benefits for the consumer and may possibly add value to the coming experience. Perceived value such as feeling good, enjoying a meal with friends or relatives, learning from reading a book, contemplating, and searching for novel experiences needs to be taken into consideration regarding experiential consumption. In 1995 Holt published the key article on “how consumers consume”, presenting four consumption forms: experiencing, playing, interaction, and classification. While experiencing and playing are described as happening “in-the-moment”, delineated as autotelic consumption behaviour, the two latter forms are described as instrumental consumption behaviour. This classification of consumer behaviour demonstrates the imperative of recognizing the construct “time” in consumer behaviour—when does a tourist participate in creating value, in addition to “why” and “how”.

Tourist consumption includes three phases of consumption, i.e., before, during, and after the experience (Prebensen, Woo, Chen, & Uysal, 2012, 2018). In the book chapter (Chapter 2) by the editors (Creating experience value in tourism), a tourist experience driver model (TEDM) including personal and environmental factors as well as the trip partaking experience is outlined. The personal driver relates to an individual’s characteristics and is described to be comparatively profound and the most diverse and comprehensive driver—ranging from socio-demographic traits to psychological elements such as personality. The environmental driver deals with non-personal influences such as appealing, informative promotion materials of the destination giving rise to an induced image and consequently driving tourists’ decisions. The trip partaking experience starts as early as the tourist shows a desire to take a trip and motivates the consumer to take further trip-related actions in terms of decisions and booking. While being at the destination, the tourist will make numerous evaluations, dependent of their expectations. In experiential consumption, most tourists choose an active way of dealing with situations and people (Prebensen & Foss, 2011), indicating the imperative of acknowledging the consumer as an active part in creating value in tourism experiences.

The foundational premises are that tourists travel because they want to, and not because they must. They travel to pursue personal interests, enjoy other environments, and nurture personal needs and wants. This simple, but major, aspect of travelling matters—and brings major concern into the experiential side of all consumption. Subsequently, tourism provides empirical as well as theoretical perspective into consumer behaviour literature.

Consumers’ role as resource integrators in value creation processes is discussed in the literature (e.g., Baron & Harris, 2008; Navarro, Andreu, & Cervera, 2014;Vargo & Lusch, 2004). According to these scholars, research reveals that consumers partake in co-creating value with employees, other consumers, and the setting (e.g., Carù & Cova, 2003; Grissemann & Stokburger-Sauer, 2012; Prebensen & Foss, 2011). Consumers who participate in creating value in the consumption process are shown to be more satisfied than passive agents (e.g., Navarro, Llinares, & Garzon, 2016; Prebensen et al., 2015; Troye & Supphellen, 2012). Building on the call for more research on the vital role of consumers in value creation and value perception processes (e.g., Rihova, Buhalis, Moital, & Gouthro, 2015), my research journey focused on the participating role of the tourists in value creation processes, and further on antecedents and consequences of such behaviour and value perceptions. This brings us to acknowledging the difference between consumption as a process versus consumption as a result, where tourism to a great deal encompasses the process of experiencing.

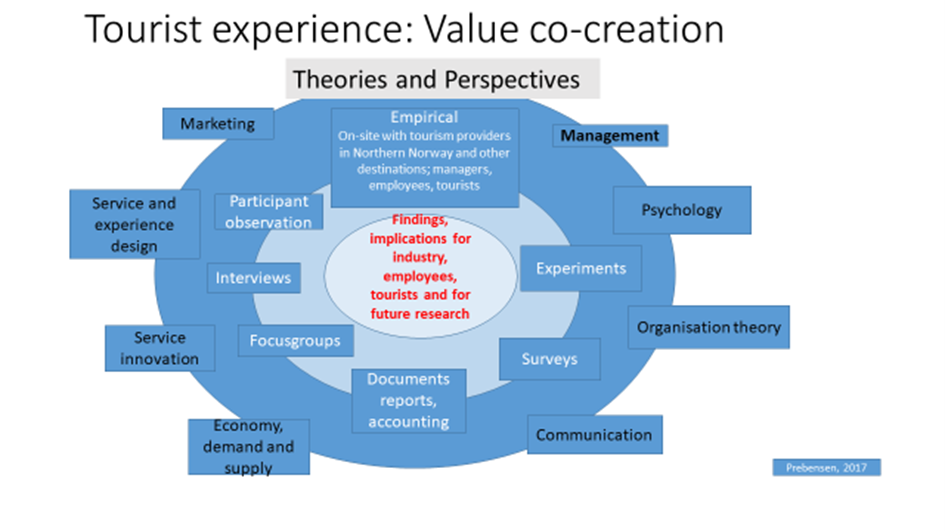

The overall research model of the project is about acknowledging why and how tourists participate in creating experience value for themselves and others, and thereby participate with various experience providers in creating value for the companies and the employees. The starting point of the research project was therefore to explore and delineate the issue of “tourism experience” and “perceived experience value”. Then the research team included various research perspectives and theories argued to be vital in experience-based consumption (the outer circle in Figure 1)—followed by definitions of research questions and hypotheses. Next, various methods and empirical settings were demarcated, with the aim of providing theoretical, empirical, and practical knowledge. In addition to publishing journal articles and books, numerous presentations were performed with a core aim to provide the industry partners with relevant knowledge (inner circle in Figure 1).

Below, an overview of the theoretical perspectives, methods used, and practical implications the project aimed for is presented.

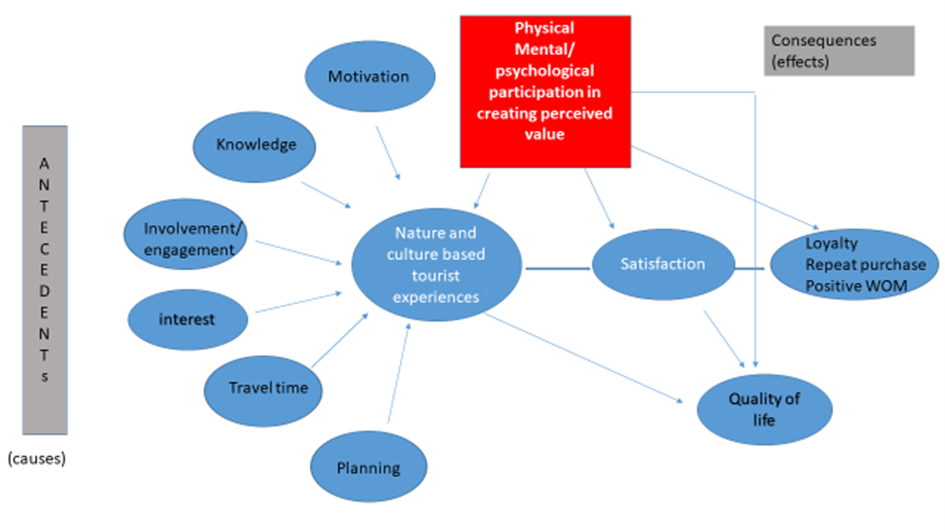

As the insights into various perspectives and theories on value co-creation in tourist experience settings developed, hypotheses and research questions emerged. A central idea was to outline and define tourist experience and experience value and explain how experience value endured through participation, i.e., co-created, by the various actors. In addition, the project aimed to explore and test the drivers (antecedents) and the consequences of experience value. The model in Figure 2 shows the key variables in the activity of tourists participating in creating experience value and the antecedents and consequences of this value creation process. The arrows in the model indicate a positive relationship between the variables, and they are outlined and tested one by one and published in tourism journals and books. Antecedents outlined are tourist motivation, involvement, knowledge and skills, and interest, as well as travel time and trip-related planning. Consequences measured are tourist satisfaction and loyalty, including intention to repurchase and telling others about the experience (word of mouth) as well as perceived quality of life. Co-creation was reflected by physical and mental participation. Felt level of mastery was also tested to affect perceived value positively.

Momentary experiences—Value perception: costs versus benefits?

Our understanding of consumer perception of value draw on research on the service quality literature (Parasuraman, Zeithaml, and Berry, 1985), servicescapes (Bitner, 1992), and experiencescapes (O’Dell & Billing, 2005). Experiential consumption, such as traveling during one’s vacation, involves “a steady flow of fantasies, feelings” (Holbrook & Hirschman, 1982, p. 132) because these feelings are valued by the tourists. Holbrook (1999) defines consumer value as a relativistic preference characterizing a consumer’s experience of interacting with some object (i.e., any goods, service, thing, place, event, or idea). In the relativistic view, consumer value is comparative, personal, and situational. Following this line of thinking, researchers have studied key factors, such as role clarity, motivation, and ability, affecting consumer participation in creating value (Meuter, Ostrom, Roundtree, & Bitner, 2000).

Most researchers define value as the results or benefits customers perceive in relation to the total costs they have expended (which include the price paid plus other costs associated with the purchase). Baier (1966, p. 40) defines value as “the capacity of a good, service, or activity to satisfy a need or provide a benefit to a person or legal entity”, and thus it includes any type of exchanged and co-created value of tangible or intangible character. Butz and Goodstein (1996) define customer value as the difference between what customers receive in relation to the purchase (benefits, quality, worth, utility) and what they pay (price, costs, sacrifices). This results in a product-related attitude or emotional bond that is used to compare what competitors offer (Gale, 1994). The challenge is to acknowledge what customers perceive as costs and benefits in various empirical settings.

Research reveals that customers who perceive that they receive “value for money” (Zeithaml, 1988) do seem to be more satisfied than those who receive less value for money. Nevertheless, this research falls short in that it excludes value as a highly personal, idiosyncratic construct, which may vary widely from one customer to another (Holbrook, 2006; Zeithaml, 1988). Likewise, it regards customer input or resources as mere perceived costs that reduce the overall value for the customer rather than adding value. Tourists consume a bundle of food, lodging, and other experiences during the journey, with different levels of service quality offered by a range of firms. All in all, these products, services, and experiences are produced and consumed in a time frame, with a certain amount of effort, and at a certain price, that more often enhances the value because tourists prefer being present, being involved, and participating in the value creation process. Finally, sometimes they even prefer to pay higher prices in a spirit of conspicuous consumption (e.g., Bagwell & Bernheim, 1996).

Tourist value as a construct resides within an evaluation framework, in terms of time, space, and costs (Crotts & Van Raaij, 1994). The value of a tourist journey or experience probably resides in the sum of many experiences. Sheth and colleagues (1991) suggest that consumers buy or use a certain product, services, or experiences rather than another by integrating their sense of cost and benefits in their value concept. In a similar way, Williams and Soutar (2009) incorporate value for money, as a cost, into a functional value component. Woodruff (1997, p. 141) claims that value perception is “a customer’s perceived preference for, and evaluation of, those product attributes, attribute performances, and consequences arising from use that facilitate (or block) achieving the customer’s goals and purposes in use situations”. Building on Woodruff’s “perceived preference” for a tourist who prefers to spend time and effort on a tourist trip (planning, discussing, deciding, travelling, and being), the time and the effort might be regarded as a value for the tourist as well as a cost.

Tourism researchers (e.g., Gallaraza & Saura, 2006; Prebensen & Xie, 2017; Williams & Soutar, 2009) have focused on evaluation of the experiential element of consumption, delineated as perceived value. In addition to the quality of the service provider and the price paid (SERVQUAL), experiential consumption includes elements such as emotions, social impacts, and epistemic value—where the latter involves learning, searching for novel experiences, and authenticity.

To sum up, service quality measures typically include the value of personal service, the surrounding natural environment, and other tourists. However, they do not typically include the value of individual tourist resources. Prebensen, Vittersø, and Dahl (2013) revealed that tourist resources, in addition to personal service, environment, and other visitors, enhance the experienced value of a trip significantly. These findings are discussed considering the service-dominant logic, identity, and self-worth theories and the imperative of including the customer resources in recognizing experience value.

Value co-creation

Vargo and Lusch (2004, p. 2) claim that “resources are not: they become”. The present work adopted this perspective and asserted that “experience value becomes through co-creation processes”. Spending time together with family and friends, enjoying good food in a restaurant surrounded by beautiful nature, or having a physical experience walking up a mountain could be utilizing resources in producing and consuming highly worthwhile and memorable experiences (Kim, Brent Ritchie, & McCormick, 2012). The time, the effort, or even the money spent are important resources that contribute to how tourists become involved in host–guest interactions. The present research thus views the tourist as a participant in the value creation process by bringing various types of customer resources and efforts into the experience value scene.

Co-creation of experience value can be defined as the tourist’s interest in mental and physical participation in an activity and its role in tourist experiences. In essence, the customer partakes mentally and physically in an experience. A tourist journey may also function as an opportunity for tourists to shape (create) their identity or self-concept (Rosenberg, 1979). In such cases, visiting a certain destination has a symbolic value for the tourist. Research describes instrumental actions in two different ways (Holt, 1995): the journey or a certain destination may function to extend one’s self, i.e., self-extension processes (Belk, 1988) or to reorient one’s self-concept to align it with an institutionally defined identity (e.g., Zerubavel, 1991). When a consumer participates in co-creating experiences, for instance, Miller (1987) claims that unique niche products are easier for the consumer to identify with than mass-produced consumption objects. Identity-altering or self-realization processes can also be a result of a “feeling of loss” (Giddens, 1990, p. 98). It is claimed that those who cannot realize their authentic selves in everyday life may use tourist trips to reach this goal (Wang, 1999). Co-creating valuable experiences then may be a function of such identity-altering processes.

Co-creation may function as a moderator between perceived value and satisfaction (Prebensen, Kim, & Uysal, 2015) or as an antecedent for perceived experience value (Prebensen & Xie, 2017). Both hypotheses are adequate and need further investigation.

Antecedents of perceived experience value

Co-creation of experiences, as a theoretical construct, considers the consumer an active agent in the consumption and production of values (Dabholkar, 1990), and regards customer motivation, involvement, and knowledge as essentials for defining and designing the experience. In addition to participation and involvement, co-creating experiences during a vacation involves interaction with other people (e.g., host and guest) and with products and services in various servicescapes (Bitner, 1992), and results in increased (or decreased) value for themselves and others, in that it is an “interactive, relativistic, preference experience” (Holbrook, 2006, p. 715). This perspective emphasizes the emotional state of consumption (Kim et al., 2012).

The impact of the physical surrounding of servicescapes for customers and employees, along with the service provided (e.g., Parasuraman et al., 1985), involves people differently in terms of how they create and co-create their own and others’ tourist experiences.

Analysing the perceived value of experiences by the impact of individual motivation, involvement, knowledge/skills, and perceived mastering, as well as the time, effort, and money put into the value creation, provide theoretical and empirical knowledge about value creation in tourist experiences. This knowledge will help tourist providers to focus on the drivers of overall experience value for the tourist, and thus help firms enhance their own overall value as well (Smith & Colgate, 2007).

Consumer participation is outlined to reflect a state of involvement (Cermak, File, and Prince 1994). Involvement is defined as a motivational state of mind that is goal directed (Mittal, 1995). The extent to which people are interested in—and participate in—tourist activities ranges from watching passively to active enactments. The activity may further be mental portrayal and/or physical performance. As Vargo and Lusch (2004) advocate that consumers should always be acknowledged as co-creators of value, they suggest that firms can only propose or facilitate for customer value through customer participation in such creation. The degree of participation and the way customers participate may nonetheless vary (Holbrook, 1999; Pine & Gilmore, 1999). According to Pine and Gilmore, a consumer experience with an on-site activity may be consumed differently in different settings.

Interest, delineated as liking and wilful engagement in a cognitive activity, can be displayed in several ways, including active engagement, paying attention, and learning (Silva, 2006). Interest affects our emotional engagement in a task and the extent to which we engage in deeper processing (Schraw & Aplin, 1998).

Interest is related to the construct of involvement, which is commonly defined as a consumer’s enduring perceptions of the importance of the product category based on the consumer’s inherent needs, values, and interests (e.g., Mittal, 1995). Product involvement has been extensively used as an explanatory variable in consumer behaviour (Dholakia, 1997). It has been established that the level of involvement determines the depth, complexity, and extensiveness of cognitive and behavioural processes during the consumer choice process (e.g., Chakravarti & Janiszewski, 2003; Laurent & Kapferer, 1985). Interest as part of the involvement construct is therefore a central framework, vital to understanding the value enhancement processes in consumption (Chakravarti & Janiszewski, 2003). Theories of interest split into two fields: (1) interest as part of emotional experience, curiosity, and momentary motivation and (2) interest as a part of personality, individual differences, and people’s hobbies, goals, and occupations (Silva, 2006). While personal, individual interest develops slowly over time and tends to have long-lasting effects on a person’s knowledge and values, situational interest is usually evoked more suddenly by something in the environment and may have only a short-term effect, marginally influencing an individual’s knowledge and values (Krapp, Renninger, & Hidi, 1991). As the present research refers to a context-specific activity, which is environmentally and spontaneously activated (Hidi & Anderson, 1992), the situational aspect of interest is focused.

Consequences of value perception

Relationships between perceived value and satisfaction have occupied researchers in recent decades (e.g., Cronin, Brady, & Hult 2000; Holbrook, 1999). Their objective has been to develop an improved understanding of the value construct and its relationship with satisfaction. Hallowell (1996, p. 29) defines satisfaction as the result of a customer’s perception of the value received “where value equals perceived service quality relative to price.” Fornell et al. (1996, p. 9) emphasize perceived value, claiming that “the first determinant of overall customer satisfaction is perceived quality . . . the second determinant of overall customer satisfaction is perceived value.”

Research (Troye & Supphellen, 2012) shows that when consumers engage in self-production, they positively bias their evaluations of an outcome (a dish) and an input product (a dinner kit). The study by Troye and Supphellen has further revealed that perceived self-integration (perceived link between self and an outcome, that is, partaking in cooking) partly mediates the positive effect of self-production on outcome evaluation. Consequently, partaking in an experiential consumption practice is mental or physical and is expected to positively affect evaluation of the experience.

A recent study by Mathis, Kim, Uysal, Sirgy, and Prebensen (2017) indicates that tourists’ satisfaction with the co-creation experience positively affects satisfaction with vacation experience and loyalty to service providers. Furthermore, the level of involvement and engagement of the co-creation experience intensifies the level of satisfaction with that experience. In addition, customer engagement is crucial for understanding customers’ behaviours such as loyalty to brands (So et al., 2014). In this respect, if a tourist can co-create value actively, then his or her satisfaction with the relationship is likely to be amplified, spilling over to the tourist’s satisfaction with the travel experience. Andrades and Dimanche (2014) argue that tourists’ state of feeling physically, mentally, and emotionally engaged with the tourism activity makes their experience memorable.

Methods

Tourists visiting firms in northern Norway made up various study cohorts through guest surveys and depth interviews with tourists. The firms chosen involved winter tourist activities in nature, such as dog sledding, sea rafting, an ice hotel visit, and snow scooter activities. Tourists visiting winter tourist companies in a three-month period (from mid-January to mid-April) were asked to complete the questionnaire. The survey was conducted by a professional consulting company and well-trained research assistants. To ensure a feasible sample size for the purpose of advanced analysis, the data collectors were instructed that a minimum of 150 valid questionnaires should be secured at each visitor attraction and for each survey. The questionnaires were randomly handed out to respondents visiting the companies on days with a certain tourist flow and were collected immediately on their completion. The collectors also provided the respondents with a brief description of the importance of answering all the questions if possible. Altogether, five surveys were conducted during the project.

Scales

Perceived value of the winter tourism experience was measured using scales developed by Williams and Soutar (2009), who generally mirrored the work of Sweeney and Soutar (2001) and partially Bello and Etzel (1985).

Antecedents such as motivation, involvement, knowledge, time, and effort were based on other empirical works. The same goes for consequences such as satisfaction and intention to revisit or recommend the experience (e.g., Petrick, Morais, & Norman, 2001).

Findings and conclusion

This story is about a research journey building on other publications in consumer experience research and focusing on differences and similarities between tourism and other consumption settings. Many side paths have been visited. Some dead ends have also been encountered. However, being part of a tourism research community has always signalled the main direction and journey. I am very pleased to see that tourism journals such as Annals of Tourism Research, Tourism Management, and Journal of Travel Research have received high ranking and impact factors—and as such have moved up the “qualification” level as well.

One of the key issues in the project presented above was to acknowledge and define tourist experience and experience value. Furthermore, we wanted to explore and test the relationship between customer participation in creating value and customers perceived experience value. Definitions and scale developments have been part of the research.

Antecedents such as motivation, involvement, and knowledge affect the perceived value of a tourist experience. As such, we replicated earlier findings in that matter. We also explored the idea of time and effort as costs in consumer behaviour—in tourism. We find that the more time and effort the tourist had employed, the higher he or she valued the experience—and the more satisfied they became. This finding is completely opposite of conclusions in consumer behaviour and branding literature, where time and effort are seen as costs for the consumer. In experiential marketing, participation and co-creation are essential to enhance the experience value for the customers.

Furthermore, customers not only want to participate in value creation, but the co-creation of value is also vital for tourist evaluation of the experience (satisfaction), which is a premise for future intentions to revisit the place. Our findings imply that the aim of enhancing tourists’ intention to revisit depends on their participation in creating experience value (physically and emotionally). Felt mastering shows the same tendency, pointing to an important issue for tourism businesses: exploring their customers’ mastering levels and developing experiences within their range of mastering.

My research journey may in many ways be compared to a tourist journey. In aiming for publications and research funding, you experience that it is in the process and in the relationships developed where you find the most valuable questions and answers. However, the most important lesson learned is the importance of being part of highly skilled scholarly teams, i.e., the American team (leading partners: Prof. Chen and Prof. Uysal), the Australian and Asian team (leading partners, Prof. Lee, Asst. Prof. Tkaczynski), the European team (leading partners: Prof. Campos, Prof. Font, Prof. Ramkisson), and the Scandinavian team (leading partners: Prof. Lyngnes, Prof. Lee, Prof. Björk, Prof. Mossberg, and Prof. Kleiven).

Written by Nina Prebensen, USN University of South-Eastern Norway (USN), Norway

Read Nina’s letter to future generations of tourism researchers

References

Andrades, L., & Dimanche, F. (2014). Co-creation of experience value: A tourist behaviour approach. In Prebensen, Chen & Uysal (Eds.) Creating experience value in tourism, Oxfordshire: CABI, 95-112.

Bagwell, L. S., & Bernheim, B. D. (1996). Veblen effects in a theory of conspicuous consumption. American Economic Review, 86(3), 349–373

Baier, K. (1966). What is value? An analysis of the concept. In K. Baier & N. Rescher (Eds.), Values and the future: The impact of technological change on American values (pp. 33–67). New York, NY: Free Press.

Baron, S., & Harris, K. (2008). Consumers as resource integrators. Journal of Marketing Management, 24(1–2), 113–130. http://dx.doi.org/10.1362/ 026725708X273948.

Bello, D. C., & Etzel, M. J. (1985). The role of novelty in the pleasure travel experience. Journal of Travel Research, 24(1), 20-26.

Belk, R. W. (1988). Possessions and the extended self. Journal of consumer research, 15(2), 139-168.

Bitner, M. J. (1992). Servicescapes: The impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. Journal of Marketing, 56(2), 57–71.

Butz, H. E., Jr., & Goodstein, L. D. (1996). Measuring customer value: Gaining the strategic advantage. Organizational Dynamics, 24, 63–77.

Carù, A., & Cova, B. (2003). Revisiting consumption experience: A more humble but complete view of the concept. Marketing Theory, 3(2), 267–286.

Cermak, D. S., File, K. M., & Prince, R. A. (1994). Customer participation in service specification and delivery. Journal of Applied Business Research (JABR), 10(2), 90-97.

Chakravarti, A., & Janiszewski, C. (2003). The influence of macro-level motives on consideration set composition in novel purchase situations. Journal of Consumer research, 30(2), 244-258.

Cronin Jr, J. J., Brady, M. K., & Hult, G. T. M. (2000). Assessing the effects of quality, value, and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. Journal of retailing, 76(2), 193-218.

Crotts, J. C., & Van Raaij, W. F. (Eds.). (1994). Economic psychology of travel and tourism. New York, NY: Haworth Press.

Dholakia, U. M. (1997). An investigation of the relationship between perceived risk and product involvement. ACR North American Advances.

Fornell, C., Johnson, M. D., Anderson, E. W., Cha, J., & Bryant, B. E. (1996). The American customer satisfaction index: nature, purpose, and findings. Journal of marketing, 60(4), 7-18.

Gale, B. T. (1994). Managing customer value. New York, NY: Free Press.

Gallaraza, M. G., & Saura, I. G. (2006). Value dimensions, perceived value, satisfaction and loyalty: An investigation of university students’ travel behaviour. Tourism Management, 27, 437–452.

Giddens, A. (1990). The Consequences of Modernity. Standford: Stanford University Press

Grissemann, U. S., & Stokburger-Sauer, N. E. (2012). Customer co-creation of travel services: The role of company support and customer satisfaction with the co-creation performance. Tourism Management, 33(6), 1483–1492.

Grönroos, C. (2006). On defining marketing: Finding a new roadmap for marketing. Marketing Theory, 6(4), 395–417.

Krapp, A., Renninger, K. A., & Hidi, S. (1991). Interest, learning, and development: The questions and their context. The role of interest in learning and development. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Hidi, S., & Anderson, V. (1992). Situational interest and its impact on reading and expository writing. The role of interest in learning and development, 11, 213-214.

Holbrook, M. B. (Ed.). (1999). Consumer value: A framework for analysis and research. London; Psychology Press. Routledge.

Holbrook, M. B. (2006). Consumption experience, customer value, and subjective personal introspection: An illustrative photographic essay. Journal of Business Research, 59(6), 714–725.

Holbrook, M. B., & Hirschman, E. C. (1982). The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. Journal of Consumer Research, 9(2), 132–140.

Hallowell, R. (1996). The relationships of customer satisfaction, customer loyalty, and profitability: an empirical study. International journal of service industry management.

Holt, D. B. (1995). How consumers consume: A typology of consumption practices. Journal of Consumer Research, 22(1), 1–16.

Kim, J.-H., Brent Ritchie, J. R., & McCormick, B. (2012). Development of a scale to measure memorable tourism experiences. Journal of Travel Research, 51(12), 11–25.

Laurent, G., & Kapferer, J. N. (1985). Measuring consumer involvement profiles. Journal of marketing research, 22(1), 41-53.

Lusch, R. F., & Vargo, S. L. (2006). Service-dominant logic: Reactions, reflections and refinements. Marketing Theory, 6(3), 281–288.

Mathis, E. F., Kim, H. L., Uysal, M., Sirgy, J. M., & Prebensen, N. K. (2016). The effect of co-creation experience on outcome variable. Annals of Tourism Research, 57, 62–75.

Meuter, M. L., Ostrom, A. L., Roundtree, R. I., & Bitner, M. J. (2000). Self-service technologies: Understanding customer satisfaction with technology-based service encounters. Journal of Marketing, 64(3), 50–64.

Miller, D. (1987). The structural and environmental correlates of business strategy. Strategic management journal, 8(1), 55-76.

Mittal, B. (1995). A comparative analysis of four scales of consumer involvement. Psychology & marketing, 12(7), 663-682.

Navarro, S., Andreu, L., & Cervera, A. (2014). Value co-creation among hotels and disabled customers: An exploratory study. Journal of Business Research, 67(5), 813–818.

Navarro, S., Llinares, C., & Garzon, D. (2016). Exploring the relationship between co-creation and satisfaction using QCA. Journal of Business Research, 69(4), 1336–1339.

O’Dell, T., & Billing, P. (Eds.). (2005). Experiencescapes: Tourism, culture and economy. Copenhagen Business School Press DK.

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1985). A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. Journal of Marketing, 49(4), 41–50.

Petrick, J. F., Morais, D. D., & Norman, W. C. (2001). An examination of the determinants of entertainment vacationers’ intentions to revisit. Journal of Travel Research, 40(1), 41–48.

Pine, B. J., & Gilmore, J. H. (1999). The experience economy: work is theatre & every business a stage. Harvard Business Press.

Prahalad, C. K., & Ramaswamy, V. (2004). Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18(3), 5–14.

Prebensen, N. K., Chen, J. S., & Uysal, M. S. (2014). Co-creation of tourist experience: Scope, definition and structure. Creating Experience Value in Tourism, 1–10. 2nd. Ed. CABI: Oxfordshire, UK.

Prebensen, N. K., Kim, H., & Uysal, M. (2015). Cocreation as moderator between the experience value and satisfaction relationship. Journal of Travel Research, 1–12. doi:10.1177/0047287515583359

Prebensen, N. K., Vittersø, J., & Dahl, T. I. (2013). Value co-creation significance of tourist resources. Annals of tourism Research, 42, 240-261.

Prebensen, N. K., Woo, E., Chen, J. S., & Uysal, M. (2012). Experience quality in the different phases of a tourist vacation: A case of northern Norway. Tourism Analysis, 17(5), 617–627.

Prebensen, N. K., & Xie, J. (2017). Efficacy of co-creation and mastering on perceived value and satisfaction in tourists’ consumption. Tourism Management, 60, 166–176.

Rihova, I., Buhalis, D., Moital, M., & Gouthro, M. B. (2015). Conceptualising customer‐to‐customer value co‐creation in tourism. International Journal of Tourism Research, 17(4), 356–363.

Rosenberg, M. (1979). Conceiving the self. New York: Basic.

Schraw, G., & Aplin, B. (1998). Teacher preferences for mastery-oriented students. The Journal of Educational Research, 91(4), 215-221.

Sheth, J. N., Newman, B. I., & Gross, B. L. (1991). Why we buy what we buy: A theory of consumption values. Journal of business research, 22(2), 159–170.

Silva, P. J. (2006). Exploring the Psychology of Interest. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Smith, J. B., & Colgate, M. (2007). Customer value creation: a practical framework. Journal of marketing Theory and Practice, 15(1), 7-23.

So, K. K. F., King, C., & Sparks, B. (2014). Customer engagement with tourism brands: Scale development and validation. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 38(3), 304-329.

Sweeney, J. C., & Soutar, G. N. (2001). Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. Journal of retailing, 77(2), 203-220.

Troye, S. V., & Supphellen, M. (2012). Consumer participation in coproduction: “I made it myself” effects on consumers’ sensory perceptions and evaluations of outcome and input product. Journal of Marketing, 76(2), 33–46.

Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2004). The four service marketing myths: Remnants of a goods-based, manufacturing model. Journal of Service Research, 6(4), 324–335.

Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2008). Service-dominant logic: Continuing the evolution. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(1), 1–10.

Wang, N. (1999). Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Annals of tourism research, 26(2), 349-370.

Williams, P., & Soutar, G. N. (2009). Value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions in an adventure tourism context. Annals of Tourism Research, 36(3), 413–438.

Woodruff, B. R. (1997). Customer value: The next source for competitive advantage. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 25(2), 139–153.

Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: a means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52, 2–22.

Zerubavel, Y. (1991). The politics of interpretation: Tel Hai in Israel’s collective memory. AjS Review, 16(1-2), 133-160.

Key works during my research journey

Books (edited or monographic) (peer-reviewed)

- Prebensen, N. K., Chen, J. S., & Uysal, M.S. (Eds.). (2017). Creating experience value in tourism. 2nd Ed. Oxfordshire: CABI.

- Prebensen, N. K., Chen, J. S., & Uysal, M. S. (2017) (Eds.) Value co-creation in tourism. London: Routledge.

- Lee, Y.-S., Weaver, D., & Prebensen, N. K. (2017). (Eds.) Arctic Tourism Experiences. Production, consumption and sustainability. Oxfordshire: CABI.

- Chen, J. S., & Prebensen, N. K. (Eds.). (2017). Nature based tourism. London: Routledge.

- Prebensen, N. K. (2016). Fra idè til suksess. Om å samskape verdifulle eventer. (From idea to success: Value co-creation in Events). Oslo: Cappelen Damm.

- Prebensen, N. K., Chen, J. S., & Uysal, M. S. (2014). Creating experience value in tourism. Oxfordshire: CABI.

Publications (peer-reviewed)

Prebensen, N. K., Burmester, M., & Aspvik, P. (in progress). Digital business model innovation: Transformation of a film festival. Magma.

Prebensen, N. K., & Uysal, M. (2020). Value co-creation in tourism eco-systems: Operant and operand resources. In Sharpley, J. (Ed.)., The Routledge handbook of the tourist experience. London: Routledge

Björk, P., Prebensen, N., Räikkönen, J., & Sundbo, J. (2021). 20 Years of Nordic tourism experience research: a review and future research agenda. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 21(1), 26-36.

Xie, J., Tkaczynski, A., & Prebensen, N. K. (2020). Human value co-creation behavior in tourism: Insight from an Australian whale watching experience. Tourism Management Perspectives, 35, 100709.

Blomstervik, I., Prebensen, N. K., Campos, A., & Lopes Guerrilha dos Santos P.S. (2020). Novelty in tourism experiences: The influence of physical staging and human interaction on behavioral intentions. Current Issues in Tourism, 1-18.

Prebensen, N. K., & Lyngnes, S. (2020). Sustainable business models in Arctic tourism. CAUTHE 2020. Vision: New Perspectives on the Diversity of Hospitality. Report

Blomstervik, I., & Prebensen, N. K. (2019). Chapter 6, Communicating and interacting. In P. Pearce, Tourist behaviour. The essential companion. Cheltenham, UK: Edgar Elwar.

Prebensen, N. K., Uysal, M., & Chen, J. S. (2018). Value co-creation: Challenges and future research directions. In N. K. Prebensen, J. S. Chen, & M. Uysal, Creating experience value in tourism. Oxfordshire: CABI

Chen, J. S., Prebensen, N. K., & Uysal, M. S. (2018). Dynamic drivers of tourist experiences. I. In Creating experience value in Tourism (pp. 11–20). Oxfordshire: CABI Publishing.

Prebensen, N. K., Uysal, M. S., & Chen, J. S. (2018). Perspectives on value creation: Resource configuration. I. In Creating experience value in tourism (pp. 228–237). Oxfordshire: CABI Publishing.

Wang, W., Chen, J. S., & Prebensen, N. K. (2018). Market analysis of value-minded tourists: Nature-based tourism in the Arctic. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 8, 82–89.

Chen, J. S., Uysal, M. S., & Prebensen, N. K. (2017). Challenges and research directions in co-creating tourism experience. In Co-creation in tourist experiences (pp. 155–162). London: Routledge.

Prebensen, N. K. (2017). Innovation potentials through value proposals: A case study of a museum in northern Norway. In Co-creation in tourist experiences (pp. 64–75). Routledge.

Prebensen, N. K. (2017). Staging for value co-creation in nature-based experiences: The case of a surfing course at Surfers Paradise, Australia. In Co-creation in tourist experiences (36–49). Routledge.

Prebensen, N. K. (2017). Successful event–destination collaboration through superior experience value for visitors. In The value of events (pp. 74–88). Routledge.

Prebensen, N. K. (2017). The mediating effect of real-life encounters in co-writing tourism books. Tourism Management, 62, 1–9.

Prebensen, N. K., & Chen, J. S. (2017). Final remarks: Challenges and research directions. In Nature tourism (pp. 208–214). Routledge.

Prebensen, N. K., Chen, J. S., & Uysal, M. S. (2017). Co-creation in tourist experiences. In Contemporary geographies of leisure, tourism and mobility (p. 67). Routledge.

Prebensen, N. K., Chen, J. S., & Uysal, M. S. (2017). Tourist experience creation: An overview. In Co-creation in tourist experiences (pp. 1–9). Routledge.

Prebensen, N. K., Lee, Y.-S., & Chen, J. S. (2017). Connectedness and relatedness to nature: A case of neo-Confucianism among Chinese, South Korean and Japanese tourists. In Nature tourism, (pp. 57–67). Routledge.

Prebensen, N. K., & Lyngnes, S. (2017). Responsible fishing tourism in the Arctic. In Arctic tourism experiences. Production, consumption and sustainability (pp. 140–148). CABI Publishing.

Prebensen, N. K., & Xie, J. (2017). Efficacy of co-creation and mastering on perceived value and satisfaction in tourists’ consumption. Tourism Management, 60, 166–176.

Vittersø, J., Prebensen, N. K., Hetland, A., & Dahl, T. I. (2017). The emotional traveler: Happiness and engagement as predictors of behavioral intentions among tourists in northern Norway. Advances in Hospitality and Leisure, 13, 3-16.

Chen, J. S., Prebensen, N. K., & Uysal, M. (2016). Tourist’s experience values and people interaction. Advances in Hospitality and Leisure, 12, 169–179.

Chen, J. S., Wang, W., & Prebensen, N. K. (2016). Travel companions and activity preferences of nature-based tourists. Tourism Review, 71(1), 45–56.

Krag, C. W., & Prebensen, N. K. (2016). Domestic nature-based tourism in Japan: Spirituality, novelty and communing. Advances in Hospitality and Leisure, 12 51–64.

Mathis, E. F., Kim, H., Uysal, M, Sirgy, J. M., & Prebensen, N. K. (2016). The effect of co-creation experience on outcome variable. Annals of Tourism Research, 57, 62–75.

Prebensen, N. K., & Rosengren, S. T. (2016). Experience value as a function of hedonic and utilitarian dominant services. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(1), 113–135.

Tkaczynski, A., Rundle-Thiele, S. R., & Prebensen, N. K. (2016). To segment or not? That is the question. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 24(1), 16–28.

Nordbø, I., & Prebensen, N. K. (2015). Hiking as mental and physical experience. Advances in Hospitality and Leisure, 11, 169–186.

Prebensen, N. K., & Foss, L. (2011). Coping and co‐creating in tourist experiences. International journal of tourism research, 13(1), 54-67.

Chen. J., Prebensen, N. K., & Lee, Y.-S. (2015). Travel companions and activity preferences of nature-based tourists. Tourism Review. 71(1), 45-56.

Prebensen, N. K., Kim, H., & Uysal, M. (2016). Cocreation as moderator between the experience value and satisfaction relationship. Journal of travel research, 55(7), 934-945.

Prebensen, N. K., Altin, M., & Uysal, M.S. (2015). Length of stay: A case of northern Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 15(sup1), 28–47. doi:10.1080/15022250.2015.1063795

Tkaczynski, T., Rundle-Thiele, S. R., & Prebensen, N. K. (2015). Segmenting potential nature-based tourists based on temporal factors: The case of Norway. Journal of Travel Research, 54(2), 251–265.