90 Destination: Tourism and Culture

Alexandra Rodrigues Gonçalves

Cultural and Creative Tourism (Sustainable) Developments

Cultural tourism is today a phenomenon identified with a growing market that encompasses a set of diverse activities that changed from its dimension to its concept in consideration as “mass consumption”. Cultural tourism was assumed as an autonomous category in the 1980s, a period in which tourist consumption of cultural heritage was consolidated (McKercher and du Cros, 2006; UNWTO, 2018).

Some authors refer that there is a tendency to consider current cultural tourism as equivalent to the forms of tourism characteristic of the 19th and early 20th centuries, in which the cultural tourist was portrayed as: a tourist with a high social and cultural level; sensitive to the heritage contemplation and highly predisposed to spend large amounts of money in the places he visits (Hughes, 2002; Vaquero, 2002). Today, cultural tourism is increasingly assumed to be a form of mass tourism, given that culture has become an object of mass consumption, and cultural tourism is seen as a manifestation of it (Richards, 2014 & 2018).

Other authors point out the increase in the level of education, the higher disposable income, the aging of the population, the growing role of women in the economy (and their more active participation in cultural activities), the search for meanings, a greater awareness of the globalization process, the virtual technologies, the effect of mass media and telecommunications and the emergence of new types of heritage attractions, as main elements affecting the rapid growth of the heritage “industry” associated with tourism (Richards, 1996; Silberberg, 1995; Timothy and Boyd, 2003), among others.

We need to have in mind when studying these domains that, culture and tourism are two different worlds, as stated by Greffe (1999). So cultural tourism poses specific challenges to the traditional actors of the tourism system. In the same sense, the work of McKercher and Du Cros (2002 & 2006) points out cultural tourism as a junction between tourism and culture, two domains that have evolved independently, are based on different ideologies and values, respond to different needs and agents, have different political leaderships, and objectives and roles that are also different in our society.

We won’t discuss the concept and the evolution of definitions of cultural tourism over time because will be much more word-consuming and less related to our motivation aim. Cultural tourism cannot be limited to visits to historical sites and monuments, but also covers the uses, customs, and traditions of the areas visited. Any of these activities engage new knowledge and experiences, this means that not only the “product” of the past (heritage tourism) is visited, but also the culture of the present, the arts related to the contemporary production of culture and even digital cultural tourism new proposals, based on interactive technologies (Gonçalves, Dorsch & Figueiredo, 2022).

The materials and research produced on cultural tourism cross the scientific literature of various fields of knowledge, namely: articles and monographs on anthropology; works on cultural policies; ethnographic articles and studies; management of cultural heritage, and the economy, among others, and most of the time are multidisciplinary approaches (Richards, 2018; UNWTO, 2018). As is recognized by Hughes: the “multi-dimensional nature of cultural tourism is reflected in a number of existing studies” (2002:167).

The most pioneering project about Cultural Tourism was ATLAS Cultural Tourism Research project founded in 1991 and is a very well-established survey on cultural tourism giving the most important input to better knowledge on the profile of cultural tourists and their typologies (Richards & Munsters, 2010). Methods are complementary and their strength resulted in creating new synergies and in broadening the phenomenon results: “There has been a dramatic growth in cultural tourism research in recent decades as the search for cultural experience has become one of the leading motivations for people to travel” (Richards & Munsters, 2010:2).

The first studies on cultural tourism research were mainly quantitative (surveys) and related to the economic impacts of tourist consumption and expenditure. With the ongoing interest in cultural tourism research, social and cultural impacts assumed importance for researchers (Richards & Munsters, 2010), and studies are becoming more multidisciplinary (Richards, 2018). A positivist research paradigm gave space for methodological sophistication, the emergence of qualitative methods, and even, the use of triangulation of methods are now being privileged (Gonçalves, 2003).

It was at the beginning of 2000 that our research on cultural and urban tourism tried to evaluate the existence of cultural tourism in the Algarve and in particular, at Faro and Silves, addressing and evaluating the role of these cities in the diversification and complementarity of “Sun and Beach” tourism product in the Algarve. Our methodological approach was multiple and used a combination of techniques – a round table, some group interviews (semi-structured), and the Delphi method – to evaluate strategic consensus between the different public and private actors of culture and tourism. The variety of techniques used to analyze results – ranging from descriptive statistics to content analysis – gave the opportunity to determine the touristic development stage of the cultural heritage in those two case studies: Faro and Silves (Gonçalves, 2003). The study of the two nearby case studies aimed to understand cultural and tourism planning and positioning of those cities in a “Sun and Sea” massified destination: the Algarve.

At that stage, discussions on cultural programming for residents and tourists were then very incipient and our analysis was recognized as a supply-side perspective, having used the Delphi technique to promote discussion between different stakeholders and generate consensus for future development of culture as a complementary product.

In our master’s research, we identified the need for better cooperation, integrated planning, and sustainable development based on the Agenda 21 proposals. Solutions to the problems of cities must be found on a basis of collaboration between all actors in the construction of the city – citizens, entrepreneurs, interest groups, and public institutions. Therefore, cooperation between all partners is essential, based on open, shared, and comprehensive information (Gonçalves, 2003).

The development of tourism based on cultural heritage requires management and planning models that promote a functional balance, between the management of tourist flows, urban planning, heritage protection, accessibility and mobility, and social and environmental respect for the territory. The sustainable development of that tourism is directly associated with integrated planning models and new partnerships that congregate public and private stakeholders (Gonçalves, 2003).

On a recent article published in the Journal of Sustainable Tourism, Rinaldi et al. (2020) recognize that universities are challenging the sustainable tourism concept and giving their contributions to research that changes destinations through new practices and activities. Major achievements come from new models of network and cooperation with civil society and local stakeholders that they named as “co-creation sustainability” rooted in participatory project development (Rinaldi e al., 2020). Also, international non-governmental authorities began paying specific attention to the need of more responsible and sustainable destination management (including the involvement of different agents and resources) (UNWTO, 2019a).

Strategic planning on culture and tourism became one of our main interests, being involved with ATLAS project and cultural tourism surveys, studying some specific cultural events (like Faro, National Capital of Culture), and giving special attention to the emergence of a post-modern tourist that values the memorable and emotional experience when visiting cultural attractions and events (in particular through our Ph.D. research that studied the tourist experience at the southern Portuguese museums). The readiness to pursue more specialized studies determined the willingness to better understand the cultural tourism experience applied to museums. A triangulation of methods was used and combined a massive survey of museum visitors, a roundtable between tourism and museum specialists, and in-depth interviews with museum managers. The biggest challenge was the analysis of all data gathered (Gonçalves, 2013).

Our subsequent research gave some relevance to heritage and cultural attractions, events, and cultural programming, proceeding with studies about tourist profiling and the quality of cultural tourism experiences. Nowadays, our expertise in new types of cultural tourism, like creative tourism or literary tourism, became the main subject of research (Cabela et al., 2021 & 2022; Gonçalves et al., 2021; Quinteiro et al., 2020).

Culture and Heritage stand out as elements of affirmation and distinction of local culture and its consolidation, constituting one of the most important components of cultural tourism. For UNWTO the operational definition of cultural tourism: “is a type of tourism activity in which the visitor’s essential motivation is to learn, discover, experience and consume the tangible and intangible cultural attractions/products in a tourism destination. These attractions/products are related to a set of distinctive material, intellectual, spiritual, and emotional features of a society that encompasses arts and architecture, historical and cultural heritage, culinary heritage, literature, music, creative industries, and the living cultures with their lifestyles, value systems, beliefs, and traditions.” (UNWTO, 2019a:30).

Most recent tourism projects and programs introduced the designation of tourism sustainable development. For instance, “cultural sustainability” is a recent concept and difficult to define, because it has implicit the participation of different perspectives and dialogue between the various fields of studies and practices. From a cultural point of view, sustainability can mean the act of developing, renewing, and maintaining human cultures that create lasting relationships with other people and the natural world (Benediktsson, 2004). Today, sustainable tourism integrates the economic, sociocultural, and environmental fields and the recommendations of UNWTO require the alignment with 17 Sustainable Development Goals (UNWTO, 2019b: 22).

Howard Hughes in 2002 recognized that some further analysis was necessary on cultural tourism: “Cultural tourism is widely regarded as a growing and particularly beneficial element of tourism. The study of it, however, is restricted by general confusion about what it is. The term is applied to visits to a wide range of cultural attractions and is applied regardless of the nature of the visitors’ interest in those attractions. There are numerous dimensions – scope, type, time and travel – to cultural tourism.” (Hughes, 2002:172).

We also perceived that sustainable cultural tourism is not only about cultural tourism, it means a holistic and integrated approach. In 2019 the European Commission (EC) established a recommendation on sustainable cultural tourism definition integrating the interaction of the host community, visitors, and industry (EC, 2019). The complexity of building a sustainable relationship between different stakeholders and bringing the community to be engaged in the process is very challenging but is the only way to build better places to live and visit.

Emerging trends and challenges

We have been witnessing over the last decades a total transformation in the cultural domain and functions, under urban economies (Arcos-Pumarola, 2019: 275). Culture is recognized as an important element to populations’ self-esteem, for the feeling of place belonging development, social cohesion, quality of life of local communities, and economic value added. Its influence on touristic consumption and on the requalification of tourist destinations is being recognized in international strategic documents but also in applied research (OECD, 2014; UNWTO, 2018; Lazzeroni et al., 2013; Richards, 2014).

In search of signs of cultural identity, cities and regions created projects to enhance, rehabilitate and reuse their most notable heritage sets, particularly in cities in relation to their historic centers. Massive and uncontrolled use of sites and monuments by tourism can have negative effects on heritage, but can also have positive effects contributing to the protection of these spaces and generating socio-cultural, economic, and social benefits for all the populations involved (Richards and Bonink, 1995). All that requires equipment and resources to have: the capacity to develop means and ways to increase attendance; self-financing capacity through revenue creation and control over operating costs; ability to develop operational policies and practices focused on customer service, partnerships, and packaging opportunities; remain open to new entrepreneurial approaches, while continuing to pursue heritage preservation (Silberberg, 1995).

Apparently, opposites, the concepts of culture and economy are increasingly closer, although with more critical reflections on this approximation, especially on the cultural side. During the 1980s’ there was a boom of cultural and heritage offers (Hewison, 1987), but with the twenty-first-century cultural tourism changed: intangible heritage becomes more important; bigger attention was given to studies on minorities and indigenous communities; geographical expansion of cultural tourism research; new paradigms – mobilities, performing authenticity, cultural representations, and creativity (Richards, 2018).

However, the debates associated with the relationship of tourism in the management and planning of cultural heritage largely transcend these issues or even the nowadays trend of asking for more active participation by communities. Figure 1 seeks to systematize some of the most current debates on the management of cultural heritage and tourism (mainly in the urban context and in relation to over-tourism).

When discussing the divergences and convergences between tourism agents, those responsible for cultural heritage and the local community, we must recognize that many heritage sites are highly valued by local and regional communities, who naturally become their protectors. Communities want to develop tourism, but also protect their privacy, and are concerned about the effects that tourism can bring, so is fundamental to plan the involvement of local communities; take into account cultural or religious sensitivities; identify and consult local community leaders; analyze ways in which the local population can play an active role in the management and operation of the tourist attraction (“the friends of the heritage”; volunteer activities; “story telling”; guided tours; among others); seek to maximize the benefits to the local community and reduce or avoid negative impacts (Gonçalves, 2003).

Heritage and cultural tourism have become the object of study of Ethnography and Anthropology trying to better understand the processes of acculturation and appropriation of the visitors’ culture in destinations, and intangible heritage assumed a particular interest also. Richards identified the following “main qualitative drivers of cultural tourism” and talks about the growing interest in popular culture, and in the everyday culture of the destination; the growing consumption of intangible heritage alongside museums and monuments; the role of the arts in cultural tourism; the increased linkage between tourism and creativity, and the growth of creative tourism and at last the omnivorousness of cultural consumption (Richards, 2014).

Kirshenblatt-Gimblett (1998) evoked in particular the construction of heritage tourism and the romanticization of narratives to different groups, forcing new significances to artifacts. Recently, Richards pointed out the emerging trends for cultural tourism: Expected continuity of growth, linked mainly to the tourism overall increase; Expanding mass market; Decline of elitism in cultural tourism audience; Mobilities of residents changing and creating new paradigms: global nomads, temporary residents; Cultural object consumed is changing and integrating everyday life; New cultural tourism definition: all tourism experience implies learning; a collection of practices involving different actors and tourists themselves; Shift from tangible heritage towards new destinations that include intangible heritage; Content creation linked to mobile applications and virtual experiences; Co-creation of cultural experiences between tourists and suppliers; Multiplicity and the plurality of practices of cultural tourism and creative experiences; Visitors refuse the “tourist label”; Emergence of cultural tourism enterprises (Richards, 2018).

Today, new governance models are suggested, like place-based approaches and participatory community planning solutions, with the engagement of local citizens and tourists in the process of placemaking, participating, interacting and co-creating (Richards, 2020).

Special attention is being given to different destinations stakeholders because a tourism culture in the destination only will be achievable if residents can benefit from its development: “No tourism destination can be sustainable and competitive in the long term without hearing the local communities and residents’ voices in its tourism planning and management.(…) DMOs are in charge of making local communities aware of the socioeconomic contributions of the tourism sector and should engage local communities and closely monitor the attitudes of residents in regards to tourism development” (UNWTO, 2019b:14).

Research methods are complementary and there isn’t one better than the other, but the research problem, resources available and circumstances can determine the better option. Searching for a broader understanding of the cultural tourism experience applied to museums made us use a triangulation of methods that combined: a mass survey of the museum visitors, a roundtable with tourism and culture specialists, and in-depth interviews with museum managers. Future research trends identified Antropology and Etnography as the main innovation contributors to cultural tourism studies (Richards & Munsters, 2010). A survey gives us plenty of information from a more expressive number of people and quantified information, but there are limitations to giving us a more in deep Knowledge of qualitative problems and answers to complex research questions.

Munsters suggests an audit applied to the touristic historic city. A cultural destination experience audit is based on a combination of quantitative and qualitative research methods. The visitor experience is evaluated by combining 3 methods: personal surveys (to tourists), mystery tourist visits (to service providers), and in-depth interviews (tourist industry/service providers). ATLAS cultural tourism research can be used to evaluate the gap between expectation and experience (Munsters, 2010). That methodology was used at Maastricht in 1999 and had the participation of local authorities, tourist offices, and the tourism industry to study on hospitality image of Maastricht. Results showed that locals were concerned with identity because of the number of visitors (Munster, 2010).

It will make perfect sense to introduce systems for monitoring and evaluating visits to museums, as well as to other cultural facilities at the national level. The human resources to carry out this work must be found among professionals in this sector, but also seeking to integrate universities, through existing research centers, in a joint effort of multidisciplinary teams.

In a recent perspective paper, Richards assumed that culture is nowadays responsible for most of the content delivery to new tourism experiences. It wasn´t always like this, and cultural tourism destinations were famous for their big festivals, museums, and monuments that annually attracted thousands of cultural visitors (Richards, 2019). We will pursue defending this systematic observation and analysis of cultural attractions visitors/audiences and asking for better resources to do it from research financing institutions.

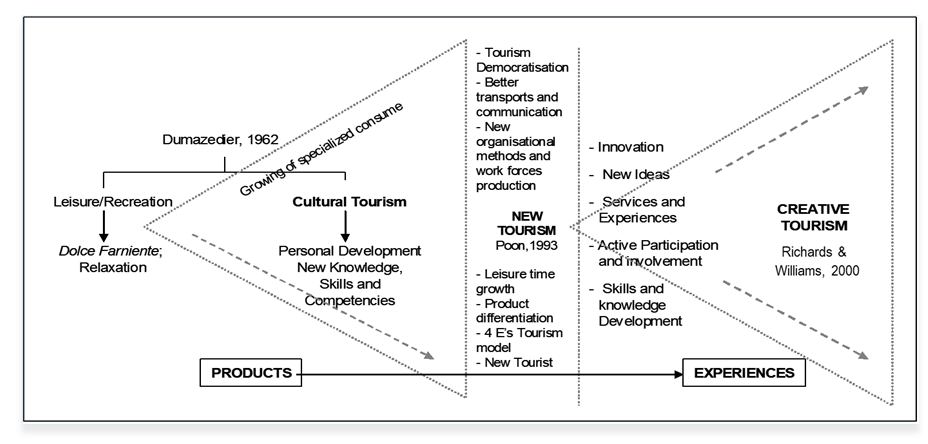

The rise of creative tourism

Getting back to people and visitors, we shell remember that tourism is about services, experiences, and feelings delivered to other people. A movement toward the discovery and demand for personalized activities outside the mainstream destinations of cultural tourism originated the demand for tailor-made and interactive manual workshops (Richards & Williams, 2000). As Quinteiro et al. argue: “The availability of a niche tourism product as a form of creative tourism, which may be based on literary tourism experiences or activities, aims to involve the tourist in participatory actions, activities that require some form of involvement – affective, artistic, cognitive, social.” (Quinteiro et al., 2020:363).

However, for the last years, the problematization of tourism in heritage sites has remained too limited to issues of heritage authenticity, forgetting the individual and his contribution to a process of experimentation, interpretation, and construction of experience. In creative tourism proposals, local communities are involved in the experiences, co-creating with the tourist: they guide workshops, lead participants, and work together. In this way, the immersion of the tourist in the local culture is achieved by learning and doing something intimately linked to the places and people where the experience takes place: “Responding to these demands and striving to provide alternative approaches to tourism development interest in creative tourism has been rising in many places, both urban and rural. Through CREATOUR[1] creative tourism research and application project in Portugal, (…) creative tourism is in an inspiring trajectory for agencies, organizations, and entrepreneurs, involved in advancing local culture-based development and cultural tourism.” (Duxbury, Carvalho e Albino, 2021:1).

The Loulé Criativo[2] is one of the CREATOUR project partners for the Algarve Region, and is a very good example of a small informal network of agents that is attracting tourists outside the coastal areas and traditional tourist circuits, offering them the opportunity to interact very closely with the communities and to get to know and learn local know-how. These offers sensitize participants to the diversity of the Algarve’s historical and cultural heritage and promote, value, preserve and recover the intangible and material cultural heritage, history and culture, and traditional arts and crafts. Our first attempts to profile creative tourists show:

“The profile of cultural tourism is well defined and supported by a long spectrum of scientific research, but little is known about the creative tourist. The few international studies dedicated to the profile of the creative tourist continue to highlight the complexity of this segment, which involves tourists from multiple generations (children, adults and the elderly) looking for authenticity, exclusivity, improving skills, and desiring contact with the local community. (…) We studied the tourists who participated in creative tourism experiences carried out by 40 institutions involved in the CREATOUR project, located in the four NUTS II regions of Continental Portugal (Norte, Centro, Alentejo and Algarve).” (Remoaldo et al., 2020:2).

In the Algarve region, tourist offers such as those associated with creative tourism meet the expectations of tourists who seek to be informed, learn and know more about the culture of the destination. Strategies for valuing the territory, and making use of its endogenous resources will bring sustainable development of tourism. The path to the development and sustainability of small-scale inland and rural areas, far from the major centers of tourist demand, seems to be this tourism strongly linked to places, people, and heritage. In the Algarve, there are experiences that make the participants – visitors and residents – feel that they are in a special place (Cabeça et al., 2021).

Creative tourism OECD definition includes: “Knowledge-based activities like producers, consumers, and places by utilizing technology, talent or skill to generate meaningful intangible cultural products, creative content, and experiences” (OECD, 2014:14). Creative tourism is considered an emerging field and research demonstrate that its contribution to local sustainable development is a reality. Matteucci et al. (2022) identify this type of cultural tourism as a space of creativity, social relationships, knowledge, and citizenship defending that local communities should be at the center of tourism planning and management.

On the other hand, the work of Stephany Cary (2004) introduces the concept of “tourist moment” and emphasizes the ephemerality of the relationship that tourists establish with the space they visit. The remarkable and memorable effect of this experience depends on the capacity of places and experiences to generate discovery and a sense of belonging to the visitor, thus introducing a change in the theoretical approach of the study of the tourist-subject, who increasingly appears as an actor with responsibility in the final result of the tourist experience (Gonçalves, 2013).

In this way, the sociological and anthropological discourses, that place the authenticity of objects and artifacts, as essential elements for the quality of the tourist experience seem to lose strength, assuming that concepts such as novelty, interactivity, and multi-sensoriality are key determinants in the tourist experience of visiting cultural resources.

The tourist moment emerges as a spontaneous experience of self-discovery and common belonging, assuming a central role in shaping the experience. However, the research that has been carried out, for example, shows that the visit to the museum emerges as the experience of the “authentic” and that the tourist, and the visitor in general, remain little active spectators in the experience of visiting the museum since the museum does not explicitly integrate an orientation towards the experience (Gonçalves, 2013). Some work can be pursued in relation to more traditional cultural attractions to become increasingly places of creative and memorable cultural experiences, where all the senses get engaged.

Virtual, augmented and metaverse cultural tourism

The acknowledgment that technology and mobility in cultural tourism will become an important dimension of future research are some of the remarks that should be taken in consideration in these domains, but the relevance is centered on “broader social changes” (Richards, 2018: 19). Tourist behavior needs to be better known and for that mobile phones and digital scanning are being used to track tourists, but could include sentiment analysis at internet booking platforms.

Another project we have been working on – iHeritage[3]– includes the development of a mobile application that answers to this technological emergence, and we really believe that will be a prevalent trend among cultural and tourism future experiences: “The logical progression from traditional tourism to the foundation for innovations and technological orientation of the overall industry was arranged with the extensive adoption of information and communication technologies (ICT’s) in tourism. Naturally, this development continues with the prevalent adoption of social media by tourists and travel agents, recognizing technology as an infrastructure in tourism that will embrace a variety of smart computing technologies that integrate hardware, software and network expertise to optimize business processes and business performances, as well as to register the mobility of tourism information and of tourism consumers. This is also a way to attract youngsters to cultural heritage and to better disseminate our culture” (Gonçalves et al., 2022:2).

Some destinations are already reconfiguring all their practices and transforming cultural experiences delivered to tourists (Wiastuti et al, 2020). One of the examples of case studies on heritage digital experiences is Jakarta, that already adopted digital technology in several museums and is working on best ways and requirements to create efficient digital information and documents applied to heritage places. There is an overall demand among millennial visitors to consume more digital experiences, that recognize that print material is not so interesting (Wiastuti et al, 2020).

The data collection and the creation of digital routes through iHERITAGE gave us the ability to promote intangible cultural elements of cultural tourism in Tavira. Through the extended international and academic agenda of the iHERITAGE project, University of the Algarve is creating the necessary synergies for the management and safeguarding of research in the field of the Mediterranean Diet, its connection with the chosen geographic locations, and the analysis of virtual routes that assemble the topics of interest of the olive industry and the fruit’s journey from the mountains to the sea. Testimonials, pictures, videos, and places are getting together to offer an integrated visit to our cultural heritage.

Today, the virtual experience in the landscape of cultural content and cultural routes has a potentially new and important role (Richards, 2018). Routes development is based on digital mapping and associates characteristics and contents to the innovative aspect. Additionally, to provide route guidance and to deliver a digital map with accurate content, one must understand the importance of authenticity in smart tourism as a truthful and genuine experience rather than a forged practice in the context of physical objects (Pine & Gilmore, 1998 & 2007).

Special attention will need to be addressed to data captured linked to smart tourism, namely issues of information governance and evaluation of information importance. A better knowledge of the context of safety and security is necessary, whilst determining the openness and universal nature of operative applications in smart tourism (Gonçalves et al., 2022).

Another advantage of technological support is creating new sources of gathering data. GPS tracking is an eminent research source, being the main problem with the integration with other software for data analysis.

One other concern comes from technology mediation and has to do with the expenses of data info-structures and information storage, following assessment concerns over sustainability costs (e.g., energy consumption and e-waste), maintenance support to technological equipment but also with the contextualization of information. ICT dependence reveals concerns in three other aspects: data overload, innovation deficiencies, and individuals’ increased desire to escape from technologies when they are on vacation. Results from iHeritage research testimony that:

“Besides all the positive aspects identified through opportunities of digital tourism to reduce negative impacts to culturally sensitive sites, one of the emerging questions identified by the research is the proliferation of apps offering different services, which most people download to their mobile devices and the lack of integration of information related to tourism destinations. Additional remarks can result from the difficulties in choosing interesting narratives that are able to keep visitors interested and make the digital experience memorable.” (Gonçalves et al., 2022:9).

In turn, one of the great challenges of cultural and heritage tourism is related to the ways of reconstructing the past through interpretation, which shall be rigorous and scientifically proven before coming available to the global tourist.

Conclusion

There is growing mobility of people in nowadays world that poses several challenges to the conviction that we travel to know more about the lives and culture of others. The change operated by globalization, liberalization, and digitalization of work is bringing new paradigms to tourist and tourism studies. Even residential tourism is fading out with the emergence of new mobilities that don’t have associated with buying houses or establishing temporary employment contracts.

Digital content availability and new technologies will also interfere with cultural tourism’s future development, not only determining new visitors’ behaviors but also reconfiguring the different stakeholders’ interactions. Other aspects to consider are the rediscovery of the links between tangible and intangible heritage, the use of virtual applications to make available new content and products, the strengthening between tourism and the creative economy, and the emergence of new ways to do cultural tourism (Gonçalves et al., 2022; Richards, 2018).

Community-based approaches or even placed-based approaches are very complex and difficult for academic and institutional bodies, not only because of the resources available but mainly because of the engagement with the community that it requires. In our view, some other stereotyping about the academy can also add difficulties to a closer approach to local stakeholders.

In fact, research demonstrated that is really necessary more networking to create transformation and promote sustainable development. Every place is different and a one namely, through creative idealabs and the co-creating process, we can be not only facilitators of innovative development in tourism, but also scientific consultants and providers of new links between different actors (Cabeça et al., 2022). We can never forget that different stakeholders’ knowledge can give different and complementary contributions to cultural and tourism sustainable development.

The dynamism of these areas proves to be essential for the innovation and creativity of the tourism and cultural sectors, so it will be necessary to create more knowledge, in order to create more value between tourism and culture.

Written by Alexandra Rodrigues Gonçalves, Integrated Researcher Cinturs – Research Centre for Tourism, Sustainability and Well-being; Research Collaborator CiTur Algarve; University of Algarve, Portugal

References

Arcos-Pumarola, J. (2019) Assessing literary heritage policies in the context of creative cities. Journal of Spatial and Organizational Dynamics, vol. VII (4), 275-290.

Benediktsoon, G. (2004) Museums and Tourism. Stakeholders, resource and sustainable development, Master Thesis, International Museum Studies, Universidade de Göteborgs.

Cabeça, S., Gonçalves, A., Marques, J. e Tavares, M. (2021) Valorizar o Interior Algarvio. Experiências de Turismo Criativo da rede CREATOUR em territórios de Baixa Densidade; Serra, J., Marujo, N., Borges, M., Lima, J. (dir) Turismo Rural e Turismo Comunitário no Espaço Ibero-Americano, Publicações de CIDEHUS, ISBN: 9791036572043, DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/books.cidehus.15812.

Cabeça, S., Gonçalves, A., Marques, J. F., & Tavares, M. (2022). Idea Laboratories: Providing Tools for Creative Tourism Agents. Revista Turismo & Desenvolvimento, 38, 181-194. DOI: https://doi.org/10.34624/rtd.v38i0.27412.

Cary, S. (2004) The tourist moment, Annals of Tourism Research, Volume 31 (1), pp.61-77.

Duxbury, N., Carvalho, C.,& Albino, S. (2021) An Introduction to creative tourism development: Articulating local culture and travel. Duxbury, N., Albino, S., Pato de Carvalho, C. (eds) Creative Tourism: Activating Cultural Resources and Engaging Creative Travellers, CABI, 1-13.

European Commission (2019), Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture, Sustainable cultural tourism, Publications Office, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2766/400886.

Gonçalves, A. (2003) A componente cultural do Turismo Urbano como oferta complementar ao produto “sol e praia”: o caso de Faro e Silves. Lisboa: Gabinete de Estudos e Prospectiva Económica/Instituto de Financiamento e Apoio ao Turismo.

Gonçalves, A. (2013) A cultura material, a musealização e o turismo: a valorização da experiência turística nos museus nacionais. Tese de Doutoramento, Universidade de Évora, DOI: http://hdl.handle.net/10400.1/3155.

Gonçalves, A., Borges, R., Duxbury, N., Carvalho, C., Costa, P. (2021) Policy recommendations on creative tourism development in small cities and rural areas: Insights from the CREATOUR project in Portugal. . Duxbury, N., Albino, S., Pato de Carvalho, C. (eds) Creative Tourism: Activating Cultural Resources and Engaging Creative Travellers, CABI, 254- 260.

Gonçalves, A., Dorsch, L. & Figueiredo, M. (2022). Digital Tourism: An Alternative View on Cultural Intangible Heritage and Sustainability in Tavira, Portugal. Sustainability. 14(5). Sustainable Brand Strategies in Social Media in Hospitality and Tourism (special Issue), DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052912.

Greffe, X. (1999) “Les rapports entre l’offre culturelle et le public touristique: une opportunité pour la culture, le tourisme et l’economie”, Casellas, D. (ed.) Cultura i turismo, Girona: Xarxa d’Escoles de Turismo, pp.56-84.

Hewison, R. (1987) The heritage industry: Britain in a climate of decline. London: Methuen.

Hughes, H. (2002) “Culture and tourism: a framework for further analysis”. Managing Leisure (7), 164-175, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/1360671022000013701.

Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, B. (1998) Destination Culture: Tourism, Museums, and Heritage. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lazzeroni, M., Bellini, N., Cortesi, G. & Loffredo, A. (2013) The territorial approach to cultural economy: New opportunities for the Development of Small Towns, European Planning Studies, 21 (4), 452-471, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.722920.

McKercher, B. e du Cros, H. (2002) Cultural Tourism: the partnership between tourism and cultural heritage management. Binghampton: The Harworth Press.

McKercher, B. e du Cros, H. (2006) Culture, Heritage and Visiting Attractions. Costa, C. e Buhalis, D. (eds.) Tourism business frontiers: consumers, products and industry. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 211-219.

Munsters, W. (2010) The Cultural Destination Experience Audit Applied to the Touristic historic city. Richards, G. & Munsters, W. (Eds.) Cultural Tourism Research Methods. 52-60. CABI.

OCDE (2014) Tourism and Creative Economy. Paris: OCDE.

Pine, B. J., & Gilmore, J. H. (1998). Welcome to the experience economy. Harvard Business Review, 76, 97–105.

Pine, B. J. & Gilmore, J.H. (2007). Authenticity: What Consumers Really Want. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press Center.

Prentice, R. (2001). Experiential Cultural Tourism: Museums & the Marketing of the New Romanticism of Evoked Authenticity. Museum Management and Curatorship, 19 (1), 5–26.

Quinteiro, S., Carreira, V. & Gonçalves, A.R. (2020) Coimbra as a literary tourism destination: landscapes of literature. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 14 (3), 361-372, DOI: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/IJCTHR-10-2019-0176/full/html.

Remoaldo, P., Serra, J, . Marujo, N., Alves, J., Gonçalves, A., Cabeça, S. & Duxbury, N. (2020) Profiling the participants in creative tourism activities: Case studies from small and medium-sized cities and rural areas from Continental Portugal, Tourism Management Perspectives, 36, 12 p., DOI: https://doi.org//10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100746.

Richards, G. (ed.) (1996). Cultural Tourism in Europe. Wallingford: Cab International.

Richards, G., & Bonink, C. (1995). Marketing cultural tourism in Europe. Journal of Vacation Marketing. 1(2): 172-180. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/135676679500100205.

Richards, G., & Wilson, J. (2006) Developing creativity in tourist experiences: A solution to the serial reproduction of culture? Tourism Management, 27(6): 1209–1223.

Richards, G. & Munsters, W. (2010a) Developments and Perspectives in Cultural Tourism Research. Richards, G. & Munsters, W. (Eds.) Cultural Tourism Research Methods.1-12. CABI.

Richards, G. & Munsters, W. (2010b) Methods in Cultural Tourism Research: the State of the Art.

Richards, G. & Munsters, W. (Eds.) Cultural Tourism Research Methods. 209-214. CABI.

Richards, G. (2014) Tourism trends: The convergence of culture and tourism. https://www.academia.edu/9491857.

Richards, G. (2018) Cultural tourism: A review of recent research and trends. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management. 36, pp. 12-21, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2018.03.005.

Richards, G. (2019) “Culture and tourism: natural partners or reluctant bedfellows? A perspective paper”, Tourism Review, 75 (1), 232-234, DOI: 10.1108/TR-04-2019-0139.

Richards, G. (2020) “Designing creative places: the role of creative tourism”, Annals of Tourism Research, (85), 1-10, https://doi.org/10.106/j.annals.2020.102922.

Rinaldi, C., Cavicchi, A. & Robinson, R. (2020). University contributions to co-creating sustainable tourism destinations. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1797056.

Silberberg, T. (1995) “Cultural Tourism and Business Opportunities for Museums and Heritage Sites”. Tourism Management. vol.16, (5), pp.361-365.

Smith, M. (2009) Issues in Cultural Studies. (2nd edition) Routledge: London & New York.

Timothy, D. e Boyd, S. (2003) Heritage Tourism, Edinburgh: Pearson Education Limited.

Vaquero, M. de La Calle (2002) La ciudad histórica como destino turístico. Ariel Turismo, Barcelona.

Wiastuti, R. D. et al. (2020) Enhancing Visitor Experiences at digital Museum Concept in Jakarta. Journal of Environmental Management and Tourism. Vol. XI, 6(46): 1435-1444.

UNWTO (2018), Tourism and Culture Synergies, UNWTO, Madrid, DOI: https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284418978.

UNWTO (2019a) Tourism Definitions, UNWTO, Madrid, https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284420858.

UNWTO (2019b) Guidelines for Institutional Strengthening of Destination Management Organizations (DMOs). UNWTO, Madrid.