94 Indigenous Tourism

Lisa Ruhanen

While I research in sustainable tourism and destination management more broadly, I am particularly passionate about my program of research in Indigenous tourism. Underpinned by policy, governance and management, these research themes connect with my philosophy that tourism, as one of the largest industries in the world, can (and should) do more to benefit people and places. To give some context, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Indigenous tourism was worth some 6 billion dollars to the Australian economy and the tourism sector in Queensland accounts for 1 in 10 jobs. Tourism is an important sector for Indigenous communities to leverage employment and socio-economic opportunities.

Over the last decade, I have collaborated with Associate Professor Michelle Whitford from Griffith University on a number of projects and publications in the area of Indigenous tourism. Michelle and I have also been fortunate to work with other academics in this area including Dr Anna Carr from the University of Otago among others. Research students have also explored the area of Indigenous tourism with a Latin American perspective (Chercoles, Ruhanen, Axelsen, & Hughes, 2021).

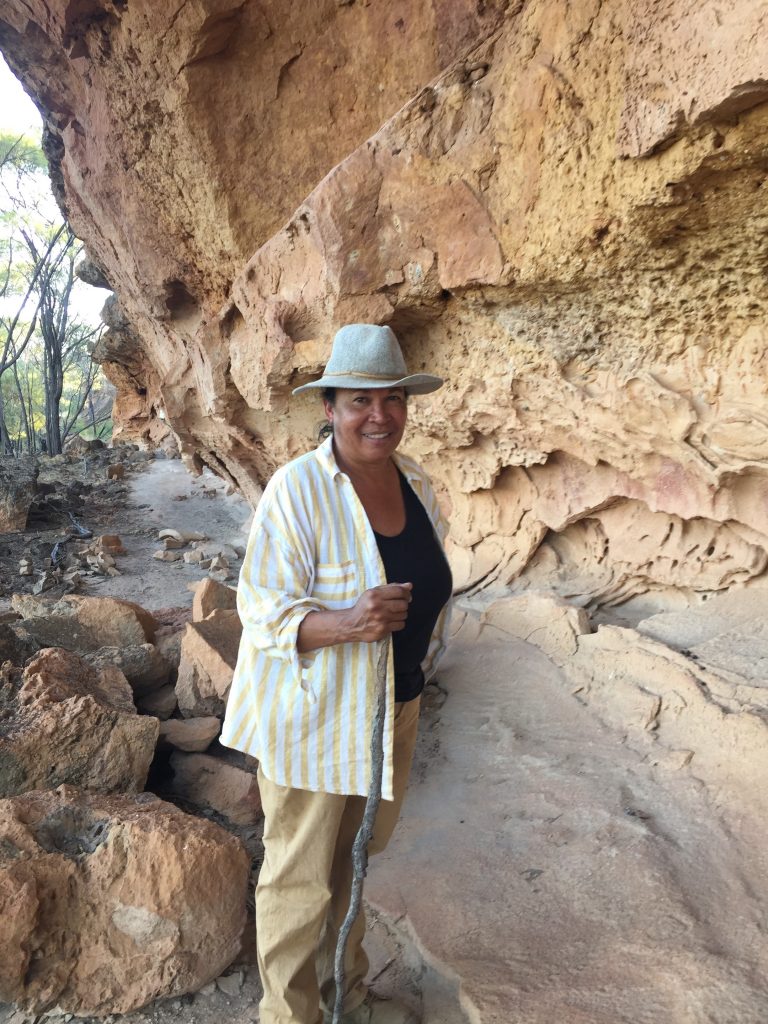

What I enjoy most about researching and collaborating in the area of Indigenous tourism is the opportunity to partner in applied research directly with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and businesses. Many of whom are leveraging sustainable business opportunities through tourism. In Queensland, this has included Quandamooka Yoolooburrabee Aboriginal Corporation on Minjerribah (North Stradbroke Island) in the Brisbane region of Queensland (Photo 1) and Yumbangku Aboriginal Cultural Heritage and Tourism Development Aboriginal Corporation (Photo 2) and their Turraburrah (Gracevale Station) in outback Queensland. Michelle and I have also enjoyed collaborating with organisations such as the Queensland Tourism Industry Council, Tourism Events Queensland, Queensland South Native Title Services, and Indigenous Business Australia on Indigenous tourism research.

Demand for Indigenous Tourism

Indigenous tourism is an important aspect of Australia’s tourism proposition and marketed as one of the key experiences which underpin Tourism Australia’s global marketing activities. While governments often claim that there is growing interest in this niche tourism experience, particularly from international visitors, this claim has not transpired into visitor flows for many Indigenous tourism businesses. To investigate this issue, Indigenous Business Australia commissioned research to understand the expectations, experiences and motivations of international and domestic tourists (n=1357) regarding Indigenous tourism products and experiences in Australia (Ruhanen, Whitford, & McLennan, 2015; Ruhanen, McLennan & Whitford, 2016).

By mapping awareness, preference and intention on an attrition curve, it was found that despite claims about international visitor interest, tourists have low spontaneous/top-of-mind awareness of Indigenous tourism experiences (less than 25% for domestic respondents and less than 20% for international respondents). Further, preferences for Indigenous tourism experiences decline to 12% and intention to visit drops to just 2%. It was also found that awareness and preferences of international visitors regarding Indigenous tourism experiences are on par with that of domestic tourists.

A series of Indigenous tourism activity and experience scenarios were presented to respondents to delve more deeply into interest and motivations for different types of products. It was found that most respondents rated the experiences on the mid-point of the appeal scale with little differentiation between the different product options presented. This suggests that consumers see Australia’s Indigenous tourism product offerings as reasonably homogenous. Further, for those respondents that did indicate a level of interest in the scenario, approximately half did not plan to participate in such an activity during their holiday. A lack of time, involvement in other activities, and cost were repeatedly cited across the experience scenarios as reasons for not participating in Indigenous tourism. Willingness to pay (another indicator of demand), in each of the scenarios was also relatively low.

Other demand studies have used netnographic methods to explore the low market appeal of Indigenous tourism products in Australia (Holder & Ruhanen, 2019). Utilising 4684 online reviews from international visitors who had participated in an Indigenous experience, it was found that those tourists that do have an Indigenous experience are overwhelmingly positive, a finding that had not typically been seen in other demand studies. The study highlighted a dissonance between those who actually participate in an Indigenous experience and non-visitors. It was also found that visitors satisfaction is more closely related to the servicescape, the physical elements and ambient environment of the experience, ahead of the cultural elements of the experience (Afiya & Holder, 2017). Although culture or the Indigenous content per se was not the most important factor identified post-experience, visitors did focus on the service-oriented nature and professionalism of their tour guide.

Indigenous Tourism Businesses

Sustainable business development has been a focus of government policies for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders for several decades. It has been noted that the development of tourism businesses not only provides wealth-creating opportunities for individuals and communities, but also provides a vehicle for invigorating and preserving Indigenous heritage, culture, knowledge, traditions, rituals and values. While Australia’s Indigenous tourism sector has numerous success stories, many businesses face barriers that inhibit their long-term sustainability. Not only do Indigenous tourism businesses need to position, promote and compete in Australia’s highly competitive tourism sector, many must also contend with a range of business development barriers including access to start-up finance and capital, recruitment and retention of employees, business development and management, as well as often contending with racism and discrimination (Ruhanen & Whitford, 2018).

Throughout the last decade, several studies have sought to explore supply side capacity in Indigenous tourism in Australia. In particular, the factors that contribute to the success and long-term viability of enterprises in Australia’s Indigenous tourism sector. To identify those underpinning factors that are associated with the success of Indigenous tourism enterprises, a study was undertaken to explore the development, operation and management of these enterprises with the objective of identifying the inhibitors and facilitators to business success from the perspectives of both community operated organisations and individual entrepreneurs (Whitford & Ruhanen, 2009).

A range of issues were uncovered through the research pertaining to drivers, inhibitors and opportunities, as well as the role and nature of government support for Indigenous tourism businesses. Business success factors were found to include training and knowledge; product development; funding; community connection; business strategies; government support; cultural sustainability; triple-bottom line; authenticity; uniqueness; collaboration; ownership; reliability; family support; commitment; commercial experience; and respect.

Indigenous Tourism Policy and Planning

As noted, tourism is often advocated as a means of creating socio-economic opportunities for Indigenous peoples and communities. In response, various levels of government will initiate policies to facilitate market growth and product development in the sector. In exploring the development of Australia’s policies for Indigenous tourism, a qualitative study of Australian State/Territory governments’ policy for Indigenous tourism was undertaken to examine the extent to which sustainable development principles are addressed (Whitford & Ruhanen, 2010). It was found that the vast majority of analysed policies demonstrated “sustainability rhetoric”, that is, they lacked the rigour and depth to realise any legitimate moves towards achieving sustainable tourism development for Indigenous peoples. As such, it was recommended that Indigenous tourism policies draw upon Indigenous diversity and, in a consistent, collaborative, coordinated and integrated manner, provide the mechanisms and capacity-building to facilitate long-term sustainable Indigenous tourism.

A collaborative example of policy and planning was seen in the development of Queensland’s First Nations Tourism Plan. Initiated by the Queensland Tourism Industry Council (QTIC), the plan was developed, driven and managed by Queensland’s First Nations peoples, with the objective of setting a framework to leverage Queensland’s First Nations cultural heritage and stewardship of country. Underpinned by the 2012 Larrakia Principles, the plan was established to inspire the development of a sustainable First Nations tourism sector that offers diverse, authentic and engaging tourism experiences. Importantly, the plan aimed to provide a much needed strategic roadmap for tourism industry bodies, state government agencies and other stakeholders to assist in the sustainable development of the Indigenous tourism sector (Appo, Costello, Ruhanen & Whitford, 2021).

Indigenous and Ethnic Minority Tourism

Since the mid-1800s, Indigenous peoples and ethnic minority groups have engaged in tourism; the Sami in Scandinavia, ethnic minority groups in Asia, and First Nations people in Canada, New Zealand, and Australia. Indigenous and First Nations peoples were often included in the Grand Tours of the aristocracy in the 1900s, and the advent of air travel in the middle of the 20th century, brought millions of tourists to experience the cultural heritage of Indigenous peoples and ethnic minority groups around the world (Ruhanen & Whitford, 2019).

Recognising that “Indigenous peoples may actively manage and provide experiences but, if not empowered, find themselves to have been ‘Other-ed’ as an ‘additional attraction’ for visitors or recreationists”, a special issue of the Journal of Sustainable Tourism Sustainable Tourism and Indigenous Peoples (https://www.tandfonline.com/toc/rsus20/24/8-9?nav=tocList) sought to explore sustainability and Indigenous tourism. The 16 papers in the special issue provided an opportunity to explore the dynamics behind an array of issues pertaining to sustainable Indigenous tourism. As Dr Anna Carr noted in the opening paper to the special issue, “These papers not only provide a long overdue balance to the far too common, negatively biased media reports about Indigenous peoples and their communities but also highlight the capacity of tourism as an effective tool for realizing sustainable Indigenous development. Throughout the papers reviewed in detail here, readers are reminded of the positive (capacity building) and negative (commodification) realities of Indigenous tourism development” (Carr, Ruhanen, & Whitford, 2016, p.1067).

Certainly, as a subject of academic inquiry, there has been considerable scholarly interest in Indigenous tourism. While researchers have long explored the many facets of Indigenous involvement in tourism, a more recent examination of research in the area found that sustainability issues had gained prominence. In a study identifying and examining the trajectory of scholarly interest in Indigenous tourism from 1980 to 2014, an analysis of 403 published journal articles showed that sustainability issues underpin and shape a substantive proportion of published Indigenous tourism research to date (Whitford & Ruhanen, 2016). However, this review highlighted that there is a need to “gain a more comprehensive understanding of Indigenous tourism from the perspective of Indigenous stakeholders, approaching its complexity in an iterative, adaptive and flexible style, and with affected stakeholders involved in the research process, knowledge creation and its outcomes. This is both an ethical imperative and a pragmatic approach to ensure the outcomes of research facilitate the sustainability of Indigenous tourism” (p.1080).

This call to action was reflected in the papers published in a 2017 publication by Goodfellow; Indigenous Tourism: Cases from Australia and New Zealand. Through a selection of case studies, the volume presented a range of issues pertaining to Indigenous tourism in Australia and New Zealand, both countries who have seen tourism grow in importance for their First Peoples. While Australia and New Zealand share similarities as well as differences in their Indigenous tourism sectors, the contributions highlighted that there is a growing expectation that Indigenous tourism research must be underpinned with an Indigenist paradigm. In the concluding chapter authored by two prominent Indigenous tourism leaders, Johnny Edmonds, the former Director of the World Indigenous Tourism Alliance, noted that “In looking forward to the next 10 to 20 years of New Zealand tourism and Maori engagement beyond the Treaty of Waitangi, recent research does beg the question of whether tourism presents Maori with the opportunity to use globalisation and development as a basis for driving the Indigenous agenda or will it continue to reinforce capitalism and western ethnocentrism” (p.245).

Written by Lisa Ruhanen, The University of Queensland, Australia

Read Lisa’s letter to future generations of tourism researchers

References

Appo, R., Costello, C., Ruhanen, L., & Whitford, M. (2021). Queensland’s First Nations Tourism Plan: Setting a Framework for a Sustainable First Nations Tourism Sector. Working paper presented at CAUTHE Conference 2021.

Carr, A., Ruhanen, L., & Whitford, M. (2016). Indigenous peoples and tourism: the challenges and opportunities for sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(8-9), 1067-1079.

Chercoles, R., Ruhanen, L., Axelsen, M., & Hughes, K. (2021). Indigenous tourism in Panama: segmenting international visitors. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 16(2), 123-135.

Holder, A., & Ruhanen, L. (2019). Exploring the market appeal of Indigenous tourism: A netnographic perspective. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 25(2), 149-161.

Holder, A., & Ruhanen, L. (2017). Identifying the relative importance of culture in Indigenous tourism experiences: netnographic evidence from Australia. Tourism Recreation Research, 42(3), 1-15.

Ruhanen, L., McLennan, C., & Whitford, M. (2016). Developing a sustainable Indigenous tourism sector: Reconciling socio-economic objectives with market driven approaches. A case from Queensland, Australia. In K. Iankova, A. Hassan & R. L’Abbé (Eds.), Indigenous People and Economic Development (pp. 205-222). Gower: Farnham.

Ruhanen, L., & Whitford, M. (2019). Cultural heritage and Indigenous Tourism. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 14(3), 179-191.

Ruhanen, L., & Whitford, M. (2018). Racism as an inhibitor to the organisational legitimacy of Indigenous tourism businesses in Australia. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(15), 1728-1742.

Ruhanen, L., Whitford, M., & McLennan, C. (2013). Demand and Supply Issues in Indigenous Tourism: A Gap Analysis. Indigenous Business Australia and Indigenous Tourism Working Group: Canberra.

Ruhanen, L., & Whitford, M. (2014). Indigenous development: Tourism and events for community development. In E. Fayos-Sola (Ed.), Tourism as an Instrument for Development: A Theoretical and Practical Study (pp. 183-194). Bingley: Emerald.

Ruhanen, L., & Whitford, M. (2012). Brisbane’s Annual Sports and Cultural Festival: Connecting with community and culture through festivals. In S. Kleinert & G. Koch (Eds.), Urban Representations: Cultural Expression, Identity, and Politics (pp. 101-117). Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies: Canberra.

Ruhanen, L., & Whitford, M. (2011). Indigenous sporting events: More than just a game. International Journal of Event Management Research, 6(1), 33-51.

Ruhanen, L., Whitford, M., & McLennan, C. (2015). Exploring Chinese visitor demand for Australia’s indigenous tourism experiences. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 24, 25-34.

Ruhanen, L., Whitford, M., & McLennan, C. (2015). Indigenous tourism in Australia: Time for a reality check. Tourism Management, 48, 73-83.

Tham, A., Ruhanen, L., & Raciti, M. (2020). Tourism with and by Indigenous and ethnic communities in the Asia Pacific region: a bricolage of people, places and partnerships. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 15(3), 243-248.

Whitford, M., Ruhanen, L., & Carr, A. (Eds.) (2017). Indigenous Tourism: Cases from Australia and New Zealand. UK: Goodfellows Publishers.

Whitford, M., Ruhanen, L., & Carr, A. (2017). Introduction to Indigenous Tourism in Australia and New Zealand. In M. Whitford, L. Ruhanen, & A, Carr (Eds), Indigenous Tourism: Cases from Australia and New Zealand (pp.1-8). UK: Goodfellow Publishers.

Whitford, M., & Ruhanen, L. (2016). Indigenous tourism research, past and present: where to from here? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(8-9), 1080-1099.

Whitford, M., & Ruhanen, L. (2014). Indigenous tourism businesses: An exploratory study of business owners’ perceptions of drivers and inhibitors. Tourism Recreation Research, 39(2), 149-168.

Whitford, M., & Ruhanen, L. (2013). Indigenous festivals and community development: A socio-cultural analysis of an Australian Indigenous festival. Event Management, 17(1), 49-62.

Whitford, M., & Ruhanen, L. (2010). Australian Indigenous tourism policy: Practical and sustainable policies? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(4), 475-496.

Whitford, M., & Ruhanen, L. (2009). Indigenous tourism businesses in Queensland: criteria for success: towards the development of a national diagnostic tool for Indigenous tourism businesses. Gold Coast: Sustainable Tourism Cooperative Research Centre.