11 Island(er) Tourism Perspectives

Teresa Borges-Tiago

Living on an island, conducting research focused on the island context, and sharing your findings with the world make you reflect on tourism behavior and the different dimensions of the unique and rich tourism ecosystem. Questions arise regarding what tourist destinations have to offer and how tourism and hospitality firms act to ensure a meaningful travel experience. Simultaneously, questions also arise regarding the distinctive components of the tourism ecosystem and regarding how tourists value these components offered to them in their traveling experiences. Therefore, for almost ten years, I focused on tourists’ behavioral patterns and the response from tourism and hospitality firms and destination marketing organizations (DMOs). In particular, I focused on tourists’ reviews and comments on which tourism and hospitality firms and DMOs are highly dependent, as well as surveys conducted with different stakeholders, bringing my marketing expertise to the tourism and hospitality field.

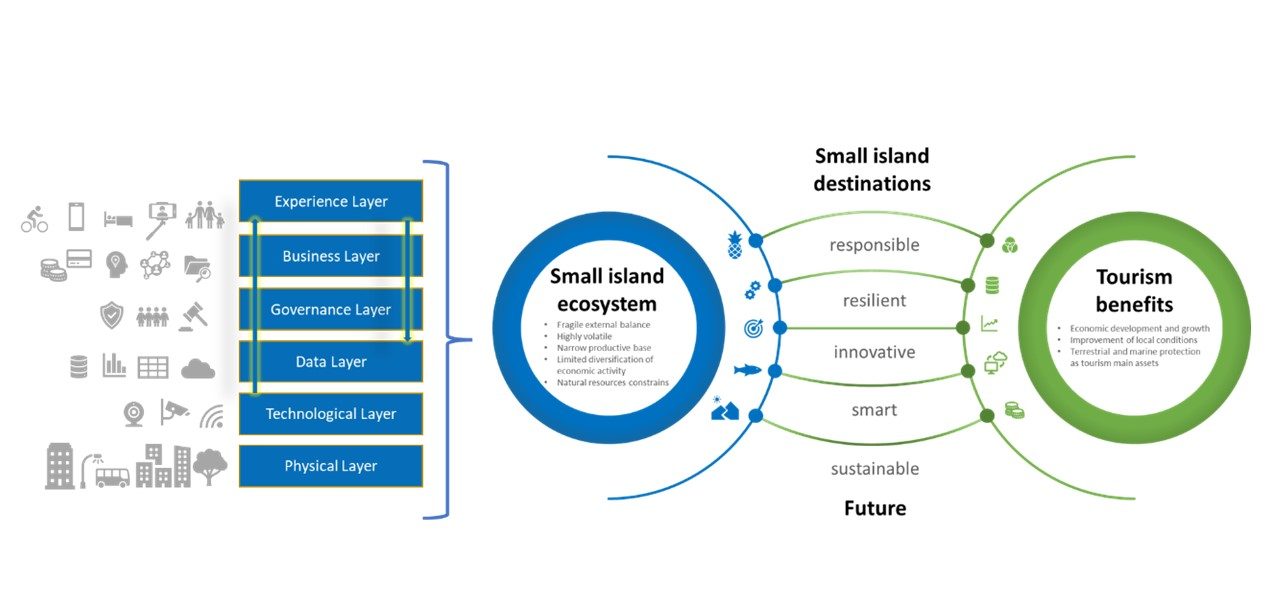

Small islands are attractive tourism destinations due to their natural resources, peripheral locations, and unique attractions (Tiago & Borges-Tiago, 2022; Tiago, Faria, Cogumbreiro, Couto, & Tiago, 2016). However, their ecosystems are fragile. They are highly dependent on the exterior and transportation and communication systems (McElroy, 2003; Ridderstaat & Nijkamp, 2016). My homeland – the Azores – is a living lab due to the economic, social, and environmental diversity found in nine small islands, which are attractive to tourism.

In the latest years, Azores has been considered a sustainable tourism destination, being the first archipelago to receive international accreditation by the Global Sustainable Tourism Council. This challenges decision-makers to run a sustainable development path and, at the same time, puts the archipelago under the spotlight and preferences of tourists.

Two main frameworks have always been used in my contributions to the field, supporting my multi-tier approach to the tourism ecosystem: smart tourism and sustainable tourism. The interconnection between these two concepts, smart tourism and sustainable tourism, could be assessed by conducting conceptual and empirical studies related to them (Buhalis, 2020; Gretzel, Sigala, Xiang, & Koo, 2015; Koo, Park, & Lee, 2017, Gossling, Ring, Dwyer, Andersson, & Hall, 2016; Maxim, 2016; Yasarata, Altinay, Burns, & Okumus, 2010), This interconnection is particularly relevant to an island context, especially in the case of small islands, due to the particularities of island ecosystems.

Tourism and technology implications

For decades, tourism and hospitality firms were of prime importance to the communication process related to tourism. The growing symbiosis between technology and tourism has changed how companies and tourists interact (Buhalis, 2020; Xiang, 2018). In this regard, social media has had the most significant impact. Changes have occurred in three main domains (Zeng & Gerritsen, 2014): (1) digital marketing strategies of tourism and hospitality players (firms and destinations); (2) channels that allow peer-to-peer communication, such as thematic social networking sites; and (3) the creation of virtual communities.

Several approaches have been taken to analyze the communication process related to tourism, one of which explored the sophistication level of tourism and hospitality websites and existing communication strategies. Following an approach similar to that presented by Limayem, Hillier, and Vogel (2003) regarding the sophistication of website communication, the efforts of three destinations—the Azores, the Canary Islands, and Madeira were evaluated (Tiago, Borges-Tiago, Varelas, & Kavoura, 2019).

Thematic social networking sites such as TripAdvisor are important tools for tourists because they help tourists decide which hotels to book and what restaurants or tourist attractions to visit. Therefore, they have become a visible part of tourism communication. To this end, several studies have been conducted since 2015 regarding tourists’ interactions on TripAdvisor (Amaral, Tiago, & Tiago, 2014; Amaral, Tiago, Tiago & Kavoura. 2015; Borges-Tiago, Arruda, Tiago, & Rita, 2021; Kavoura & Borges, 2016; Rita, Ramos, Borges-Tiago, & Rodrigues, 2022; Tiago, Amaral & Tiago 2015, 2017; Tiago, Tiago & Amaral, 2014).

Reviews from tourists, published on user-generated content (UGC) sites, may take the form of small free texts, ratings on a pre-defined scale, and photos and videos. These manifestations of users’ opinions are regarded as electronic word of mouth (eWOM) (Jeong & Koo, 2015). Tourists tend to refer to these reviews and ratings before making vacation plans (Gretzel & Yoo, 2008; Melian-Gonzalez, Bulchand-Gidumal, & Lopez-Valcarcel, 2013; Min & Park, 2012).

eWoM, generated in the form of online evaluations on specialized experience-sharing platforms, is considered reliable (Park, Wang, Yao, & Kang, 2011), and therefore, it is considered more efficient than other marketing strategies in influencing consumer behavior (Hu & Kim, 2018). eWoM often reflects a hotel’s reputation (Filieri & McLeay, 2014; Hu & Kim, 2018; Viglia, Minazzi, & Buhalis, 2016). Consequently, this influences tourists’ reservation attitudes and intentions (Hu & Kim, 2018; Zhang, Ye, Law, & Li, 2010).

eWoM, generated in the form of online evaluations on specialized experience-sharing platforms, is considered reliable (Liu & Park, 2015), and therefore, eWoM is more efficient than other marketing strategies in influencing consumer behavior (Hysa, Karasek, & Zdonek, 2021).

In general, information has the power to arouse interest. It influences buying behavior and the performance of tourism offers at large. In this sense, information may be said to directly influence the revenues of tourism firms and tourist destinations, as well as the total number of hotel and restaurant bookings. Positive information such as positive reviews is likely to increase revenues, whereas negative information such as negative reviews may damage firms’ reputations (Anagnostopoulou, Buhalis, Kountouri, Manousakis, & Tsekrekos, 2019). These factors combined directly influence tourist satisfaction and overall service expectation.

Nonetheless, as Shin, Song, and Biswas (2014) indicated, little is known about the factors that influence tourists’ decision to choose a particular platform over others when posting reviews. In this regard, some authors have noted that while some tourism and hospitality firms invite clients to post comments others refer to the influence of the platform itself by asking users to comment on past experiences (Zhou, Yan, Yan, & Shen, 2020).

Three major groups of reviews based on characteristics must be considered, regardless of the model under study. The first group is simple and easy to obtain and comprises users’ ratings, the number of useful votes received, and valence (Tiago, Couto, Faria, & Borges-Tiago, 2018). The second group is more difficult to obtain than the first and also difficult to manage. It comprises the relevance of reviews, their value to tourists, and their completeness and trustworthiness (Amaral et al., 2015). The third group considers the sentiment and tone of the expressed voice, which reflects tourists’ overall satisfaction with the experience (Rita et al., 2022).

The richness of this field has led to the development of the research project, Smart Tourism- Azores (PO 2020 ACORES-01-0145-FEDER-000017 with founding from AÇORES 2020, through FEDER – European Union). This project aimed to analyze firms’ and tourists’ behavior in the digital domain to increase the responsiveness of the regional sector tourism cluster within the RIS3 (regional specialization sectors) strategy.

The initial results of this project suggested that technology needed to be seen as an enabler in tourism development, enhancing the tourists’ experiences and providing information to all the members of the ecosystem. However, additional efforts were required in what concerns the genuinely sustainable development of the nine islands, combining the actions of the DMO and local firms to promote a sustainable tourism development valued and communicated by locals and recognized and appraised by those who visit the islands.

Tourism and sustainability

As sustainable tourism development became a key issue for tourism destination planners and managers, its concept and application received considerable attention within academia and in policy agendas at all government levels (McLennan, Ritchie, Ruhanen, & Moyle, 2014).

Since the 1990s, tourism firms, especially hotels, have undertaken different voluntary activities to demonstrate their commitment to sustainable tourism. These activities range from adopting codes of conduct to obtaining eco-labels and implementing environmental management systems (Ayuso, 2007). However, some firms consider that obtaining tourism eco-labels is expensive and time-consuming (Karlsson & Dolnicar, 2016). Additionally, eco-labels seem to have limited marketing power based on the varied responses from visitors (Patterson, Niccolucci, & Bastianoni, 2007). Therefore, lodging firms are reluctant to invest in eco-labels because they are expensive and not highly valued by clients (Karlsson & Dolnicar, 2016; Karuma, 2016). When considering sustainability in the context of hospitality and tourism, a paradox arises. On the one hand, firms communicate unique and exquisite experiences to meet and exceed tourists’ expectations. On the other hand, they communicate the measures they have taken to develop the tourism infrastructure and reduce resource consumption, which may diminish the overall experience (e.g., recommending tourists to use their towels for more than one day) (Jones, Hillier, & Comfort, 2016).

Policymakers, managers, and academics are well aware that the actions of individual entities or organizations cannot define the future of the tourism industry, implying the need for a larger local and global movement towards sustainable tourism. This need has led to the development of plans and principles by organizations that represent destinations and the tourism sector worldwide. However, a consensus is lacking on two key points: (1) whether policy efforts align with private firms’ sustainable practices (Yasarata et al., 2010), and (2) whether private tourism firms communicate on eco-labels following a contamination process.

Considering the issues related to consensus, Tiago et al. (2016) analyzed how hoteliers and guests perceive sustainable practices and accreditation systems. Further, Tiago, Gil, Stemberger, and Borges-Tiago (2021) analyzed digital sustainability communication in tourism.

The sustainable tourism approach is critical in the case of small islands and should lead to combined actions from all stakeholders. This approach promotes a balance between development and conservation and simultaneously values natural and cultural resources. Therefore, it considers the well-being of both the local population and the tourists who visit tourist destinations. As previously noted, the Azores was the first archipelago in the world to pursue a tourism destination sustainability accreditation. Aligned with this policy initiative, a new research project called the Taste Azores Sustainable Tourism Experiences (TASTE) (PO 2020 ACORES-01-0145-FEDER-000106 with founding from AÇORES 2020, through FEDER – European Union was designed. This project aimed to promote the regional gastronomic heritage, which is an intangible constituent of cultural heritage. The gastronomic heritage has proven to be a source of differentiation and a basis for initiatives to enhance the destination’s tourism offers (Galvez, Granda, Lopez-Guzman, & Coronel, 2017; Wang, 2015). The gastronomic and wine heritage of the Azores strongly reflects the local culture and can be considered a factor of differentiation and appreciation of the destination’s offer. It links the production of primary and secondary sectors with traditions, thereby creating a unique combination of sensory and rational experiences. These experiences are distinct to each of the nine islands and enhance the development of sustainable and differentiated tourism strategies in the archipelago (Tiago, Fonseca, Chaves, & Borges-Tiago, 2021).

Conclusions

I have been conducting research in the tourism and hospitality field over the past eight years. My research has led me to conclude that this field is quite rich and diverse. My conclusion is largely based on the specifications of tourist destinations and ever-evolving tourist behaviors, using my personal and woman view of the industry (Tiago, Couto, Tiago, & Faria, 2016; Tiago & Tiago, 2013). The recent Covid-19 pandemic highlighted the major challenges in the tourism industry, especially for small islands (Tiago & Borges-Tiago, 2022). It highlighted the need for a smart and sustainable approach that will promote consistent tourism development in small contexts.

Significantly, several studies related to islands have been conducted to not only support islands’ local ecosystems but also enhance tourism and hospitality knowledge worldwide. My research in this field is ongoing, and I have gained significantly from the useful insights and inspiration provided by my colleagues and friends, journals editors and reviewers, workers belonging to tourism and hospitality firms, and policymakers.

Written by Teresa Borges-Tiago, Universidade dos Açores, The Azores

References

Amaral, F., Tiago, T., & Tiago, F. (2014). User-generated content: tourists’ profiles on TripAdvisor. International Journal on Strategic Innovative Marketing, 1, 137-147.

Amaral, F., Tiago, T., Tiago, F., & Kavoura, A. (2015). TripAdvisor comments: what are they talking about? Dos Algarves. A Multidisciplinary E-journal, 26 (2), 47-67.

Anagnostopoulou, S. C., Buhalis, D., Kountouri, I. L., Manousakis, E. G., & Tsekrekos, A. E. (2019). The impact of online reputation on hotel profitability. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. 32 (1), 20-39. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-03-2019-0247.

Ayuso, S. (2007). Comparing Voluntary Policy Instruments for Sustainable Tourism: The Experience of the Spanish Hotel Sector. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 15(2), 144-159. doi:10.2167/jost617.0

Borges-Tiago, M. T., Arruda, C., Tiago, F., & Rita, P. (2021). Differences between TripAdvisor and Booking.com in branding co-creation. Journal of Business Research, 123, 380-388. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.09.050

Buhalis, D. (2020). Technology in tourism-from information communication technologies to eTourism and smart tourism towards ambient intelligence tourism: a perspective article. Tourism Review, 75(1), 267-272. doi:10.1108/TR-06-2019-0258

Filieri, R., & McLeay, F. (2014). E-WOM and accommodation: An analysis of the factors that influence travelers’ adoption of information from online reviews. Journal of Travel Research, 53(1), 44-57. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513481274

Galvez, J. C. P., Granda, M. J., Lopez-Guzman, T., & Coronel, J. R. (2017). Local gastronomy, culture and tourism sustainable cities: The behavior of the American tourist. Sustainable Cities and Society, 32, 604-612. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2017.04.021

Gossling, S., Ring, A., Dwyer, L., Andersson, A. C., & Hall, C. M. (2016). Optimizing or maximizing growth? A challenge for sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(4), 527-548. doi:10.1080/09669582.2015.1085869

Gretzel, U., Sigala, M., Xiang, Z., & Koo, C. (2015). Smart tourism: foundations and developments. Electronic Markets, 25(3), 179-188.

Gretzel, U., & Yoo, K. H. (2008). Use and impact of online travel reviews. Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2008, 35-46.

Hu, Y., & Kim, H. J. (2018). Positive and negative eWOM motivations and hotel customers’ eWOM behavior: Does personality matter? International Journal of Hospitality Management, 75, 27-37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.03.004

Hysa, B., Karasek, A., & Zdonek, I. (2021). Social media usage by different generations as a tool for sustainable tourism marketing in society 5.0 idea. Sustainability, 13(3), 1018. doi:10.3390/su13031018

Jeong, H.-J., & Koo, D.-M. (2015). Combined effects of valence and attributes of e-WOM on consumer judgment for message and product: The moderating effect of brand community type. Internet Research, 25(1), 2-29.

Jones, P., Hillier, D., & Comfort, D. (2016). Sustainability in the hospitality industry: Some personal reflections on corporate challenges and research agendas. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(1), 36-67.

Karlsson, L., & Dolnicar, S. (2016). Does eco certification sell tourism services? Evidence from a quasi-experimental observation study in Iceland. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(5), 694-714. doi:10.1080/09669582.2015.1088859

Karuma, A. K. (2016). Assessing the role of eco-rating certification scheme in promoting responsible tourism. Master Thesis, South East Kenya University. Retrieved from http://repository.seku.ac.ke/handle/123456789/1878

Kavoura, A., & Borges, M. T. T. (2016). Understanding online communities on social networks via the notion of imagined communities: the case of TripAdvisor. International Journal of Web Based Communities, 12(3), 238-261.

Koo, C., Park, J., & Lee, J.-N. (2017). Smart tourism: Traveler, business, and organizational perspectives. In: Elsevier.

Limayem, A., Hillier, M., & Vogel, D. (2003). Sophistication of online tourism websites in Hong Kong: An exploratory study. AMCIS 2003 Proceedings, 142.

Liu, Z. W., & Park, S. (2015). What makes a useful online review? Implication for travel product websites. Tourism Management, 47, 140-151. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2014.09.020

Maxim, C. (2016). Sustainable tourism implementation in urban areas: a case study of London. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(7), 971-989. doi:10.1080/09669582.2015.1115511

McElroy, J. L. (2003). Tourism development in small islands across the world. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 85(4), 231-242.

McLennan, C.-l. J., Ritchie, B. W., Ruhanen, L. M., & Moyle, B. D. (2014). An institutional assessment of three local government-level tourism destinations at different stages of the transformation process. Tourism Management, 41, 107-118.

Melian-Gonzalez, S., Bulchand-Gidumal, J., & Lopez-Valcarcel, B. G. (2013). Online Customer Reviews of Hotels: As Participation Increases, Better Evaluation Is Obtained. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 54(3), 274-283. doi:10.1177/1938965513481498

Min, H.-J., & Park, J. C. (2012). Identifying helpful reviews based on customer’s mentions about experiences. Expert Systems with Applications, 39(15), 11830-11838.

Park, C., Wang, Y., Yao, Y., & Kang, Y. R. (2011). Factors influencing eWOM effects: Using experience, credibility, and susceptibility. International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, 1(1), 74.

Patterson, T. M., Niccolucci, V., & Bastianoni, S. (2007). Beyond “more is better”: ecological footprint accounting for tourism and consumption in Val di Merse, Italy. Ecological Economics, 62(3), 747-756.

Ridderstaat, J. R., & Nijkamp, P. (2016). Small island destinations and international tourism: market concentration and distance vulnerabilities. In Self-determinable development of small Islands (pp. 159-178): Springer.

Rita, P., Ramos, R., Borges-Tiago, M. T., & Rodrigues, D. (2022). Impact of the rating system on sentiment and tone of voice: A Booking.com and TripAdvisor comparison study. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 104, 103245. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2022.103245

Shin, D., Song, J. H., & Biswas, A. (2014). Electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) generation in new media platforms: The role of regulatory focus and collective dissonance. Marketing Letters, 25(2), 153-165.

Tiago, F., & Borges-Tiago, T. (2022). Small Island Destinations. In D. Buhalis (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Tourism Management and Marketing (Vol. Forthcoming). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Tiago, F., Borges-Tiago, T., Varelas, S., & Kavoura, A. (2019). The Effect of Asymmetrical Image Projections on Online Destination Branding, Cham.

Tiago, F., Couto, J., Faria, S., & Borges-Tiago, T. (2018). Cruise tourism: social media content and network structures. Tourism Review, 73(4), 433-447. doi:doi:10.1108/TR-10-2017-0155

Tiago, F., Fonseca, J., Chaves, D., & Borges-Tiago, T. (2021). A look into the trilogy: food, tourism, and cultural entrepreneurship. Turismo sénior: Abordagens, sustentabilidade e boas práticas, 10.

Tiago, F., Gil, A., Stemberger, S., & Borges-Tiago, T. (2021). Digital sustainability communication in tourism. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 6(1), 27-34.

Tiago, M., Couto, J. P. D., Tiago, F. G. B., & Faria, S. (2016). Baby boomers turning grey: European profiles. Tourism Management, 54, 13-22. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2015.10.017

Tiago, M. T. B., & Tiago, F. G. B. (2013). The influence of teenagers on a family s vacation choices. Tourism & Management Studies, 9, 28-34. Retrieved from http://www.scielo.gpeari.mctes.pt/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2182-84582013000100005&nrm=iso

Tiago, T., Amaral, F., & Tiago, F. (2015). The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: Food Quality in UGC. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 175, 162-169.

Tiago, T., Amaral, F., & Tiago, F. (2017). Food Experiences: The Oldest Social Network…. In A. Kavoura, D. P. Sakas, & P. Tomaras (Eds.), Strategic Innovative Marketing: 4th IC-SIM, Mykonos, Greece 2015 (pp. 435-444). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Tiago, T., Faria, S. D., Cogumbreiro, J. L., Couto, J. P., & Tiago, F. (2016). Different shades of green on small islands. Island Studies Journal, 11(2), 601-618.

Tiago, T., Tiago, F., & Amaral, F. (2014). Restaurant quality or food quality: what matters the more? Paper presented at the International Network of Business and Management Journals, Barcelona.

Viglia, G., Minazzi, R., & Buhalis, D. (2016). The influence of e-word-of-mouth on hotel occupancy rate. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(9), 2035-2051. doi:10.1108/ijchm-05-2015-0238

Wang, Y. C. (2015). A study on the influence of electronic word of mouth and the image of gastronomy tourism on the intentions of tourists visiting Macau. Tourism, 63(1), 67-80. Retrieved from <Go to ISI>://WOS:000213677300005

Xiang, Z. (2018). From digitization to the age of acceleration: On information technology and tourism. Tourism Management Perspectives, 25, 147-150. doi:10.1016/j.tmp.2017.11.023

Yasarata, M., Altinay, L., Burns, P., & Okumus, F. (2010). Politics and sustainable tourism development–Can they co-exist? Voices from North Cyprus. Tourism Management, 31(3), 345-356.

Zeng, B., & Gerritsen, R. (2014). What do we know about social media in tourism? A review. Tourism Management Perspectives, 10, 27-36. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2014.01.001

Zhang, Z., Ye, Q., Law, R., & Li, Y. (2010). The impact of e-word-of-mouth on the online popularity of restaurants: A comparison of consumer reviews and editor reviews. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 29(4), 694-700.

Zhou, S., Yan, Q., Yan, M., & Shen, C. (2020). Tourists’ emotional changes and eWOM behavior on social media and integrated tourism websites. International Journal of Tourism Research, 22(3), 336-350.