26 Luxury in Tourism

Antonia Correia

“People wish to be judged not as they are but as they appear to be” (Mandeville, 1714)

Introduction

This contribution discusses the concept of luxury tourism under several ways, in order to understand the role luxury plays in the tourist choices and perceiving the leading forces that motivate tourists to choose tourism destinations based on the sense of achieving prestige and social recognition.

Luxury influences many decisions to buy. Although, today, it is widely accepted as a positive externality in the economy, it is far from being understood as a “positive” behaviour. The pejorative sense given to this type of consumption for ages, probably justifies the absence of studies around this topic. The few economists who tried to explain luxury consumption on the light of economic theory were called pejoratively sociologists and not considered, as this behaviour arose from social motivations. It was assumed that this behaviour had no economic impacts, because this does not fit any classical or neoclassical notions of value and utility and because this was seen as an irrational behaviour unfeasible to be modelled, as this represents the behaviour of the minorities (Veblen, 1902). luxury consumption was, therefore, a controversial topic in economics which has been neglected by economists for ages and it is, because of that, my favourite topic.

Only in the 1980s the growing importance of conspicuous consumption has made it an issue that deserves the attention of the economists, mainly due to its impact on economic development. At this age luxury behaviour was finally recognized as a field of knowledge within the bounds of economy, sociology, and psychology. Our first contribution on this topic is to establish the historical boundaries of this controversial topic (Correia, 2009); the second is to define luxury from from a theoretical perspective (Correia and Moital, 2009) and the third to search for a luxury definition from an applied perspective, Correia and Kozak (2012), Correia, Kozak and Kim (2018), Correia, Kozak and Gonçalves (2018).The fourth contribution relies on content analysis to enrich the meaning of luxury, Correia, Kozak and Reis (2014); Correia, Reis and Ghasemi (2020) and Correia, Kozak, and Del Chiappa (2020)

1. Historical Perspective

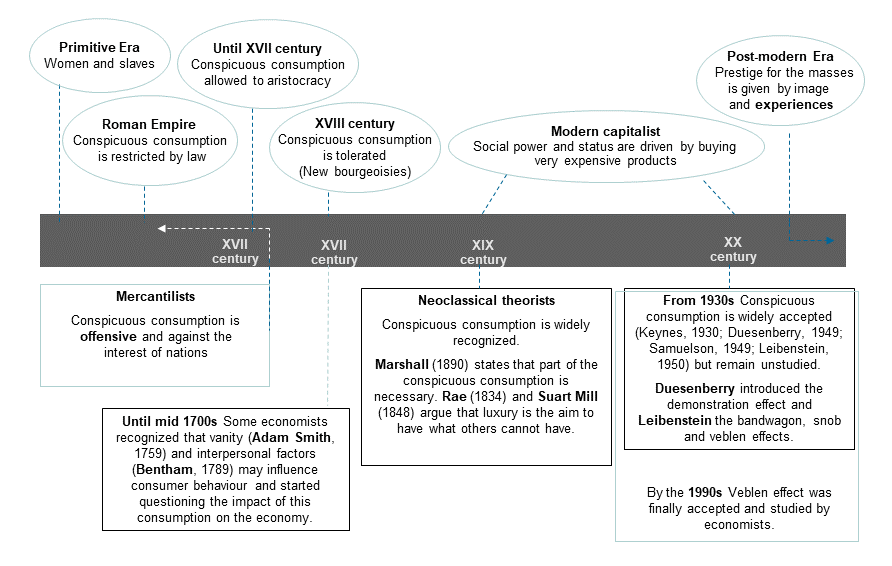

Signs of prestige consumption emerged in the early beginnings of roman society. In the roman empire, the authorities introduced laws to suppress conspicuous consumption. Those laws where extended until the seventeenth century and never worked effectively, with some minority groups behaving outrageously. In the seventeenth century the attempt to control the conspicuous consumption had been largely abandoned. Simultaneously, the economists started to question the impact this consumption had on the economy.

Conspicuous consumption appears associated with the concept of vanity (Smith, 1759) and interpersonal factors (Bentham, 1789). According to Smith (1759), vanity influences the consumer behaviour, although, for him, the opinion of others may also influence the consumption, being this a need and not a luxury.

In the nineteenth century, Rae (1834), in his principles of economy, elicited for the first time the conspicuous consumption, arguing that this is a superior form of consumption. Later, Mill (1848) defended that luxury is the desire of superiority. Only at the end of the century, Marshal (1890) assumes that luxury consumption may impact the economy positively and, therefore, it is worth being researched. The concept of utility was defined as the total pleasure or other benefits it yields and the Veblen Effect was finally accepted amongst the economists.

For Keynes (1930), the human needs are insatiable, and they fall in two different classes: primary needs and secondary needs, where the desire of superiority is the driving force. In the same vein, Samuelson (1949) accepted that much of the motivations for consumption were related with having or not having the same behaviour. At the beginning of the twenty first century, it is obvious that luxury is a part of daily life, being this century the beginning of a new brand era. Figure 1 illustrates the chronology of luxury research, this figure was elaborated by Correia (2009) based on literature review and Mason (1988).

2. A theoretical model to define luxury tourism

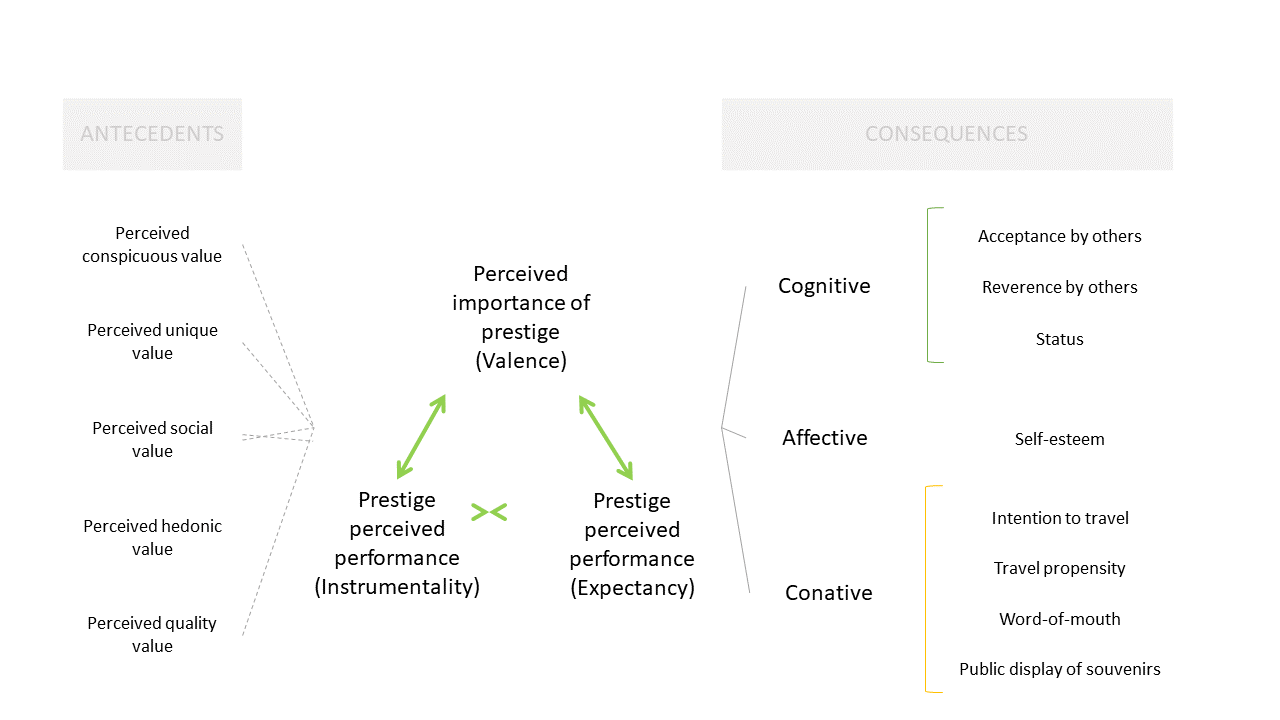

The model proposed by Correia and Moital (2009) assumes that tourists have motivations (needs and desires) which guide their actions (goals) to obtain the expected value (expectancy) that is the most valued by the tourist (valence), considering antecedents and consequences of prestige motivations. In this model, expectancy refers to the tourist’s perceptive effort in achieving the tourist experience, that results in prestige enhancement based on his or her performance in the luxury tourism consumption/experience. In general terms, it could be assumed that expectancy refers to a characteristic of the tourism experience.

On the other hand, instrumentality comprises the perceived probability that a certain destination has the attributes (performance) needed to achieve the level of prestige the tourist desires (rewards); that is, instrumentality refers to a characteristic of the product (tourism attributes). Finally, the valence component of the model refers to the extent to which prestige consumption is valued by the tourist, that is, how desirable prestige is. The model also proposes an interaction with antecedents and consequences.

Antecedents of luxury refer to those reasons why a destination or a travel experience would be perceived as prestigious and established based on the perceived value offered by the product, yet at interpersonal and personal level. At the interpersonal level, the perceived social value refers to the peer group emulation (bandwagon effect), that is the desire to conform with the others. The perceived unique value refers to the sense of achievement and uniqueness in purchasing a product or travelling to a destination where others are unlikely to go, not only because of the price, but also because of the scarcity associated with the product/service (snob effect). Snob effect is the desire to be distinguished from the common herds Furthermore, the perceived conspicuous value refers to the display of wealth (Veblen effect)– having as much as possible. At the personal level, emotional and quality value are outlined. The perceived emotional value refers to the Maslow need of self-actualization (hedonic value), that provides to the tourist the sense of fulfilment because of his or her holiday experience. Whereas the perceived quality value refers to a very high price and superior quality (perfectionist).

The consequences (goals) or responses refer to how a tourist perceives, in terms of value, the actions they take in order to achieve status from the consumption of luxury tourism experiences. Based on the trilogy of Hovland and Rosenberg (1960), i.e., cognitive-affective-conative trilogy. At cognitive level it is assumed that luxury is to achieve status and status derives from social perceptions of greater acceptance, recognition or reverence by others. At the affective level it is considered the individual’s feelings, notably in the domain of self-esteem. At the conative level is measured by the intention to revisit, to recommend and the display of mementos and artefacts, as illustrated in figure 2.

Overall, it is assumed that the greater the expectancy that travelling to the destination would result in luxury benefits, or the greater the importance of luxury for the traveller, the more intense such behavioural manifestations will be.

This model was partially tested as we are still looking to define luxury tourism. The efforts done to reach this milestone are presented in next section.

3. Luxury Definition – Applied research

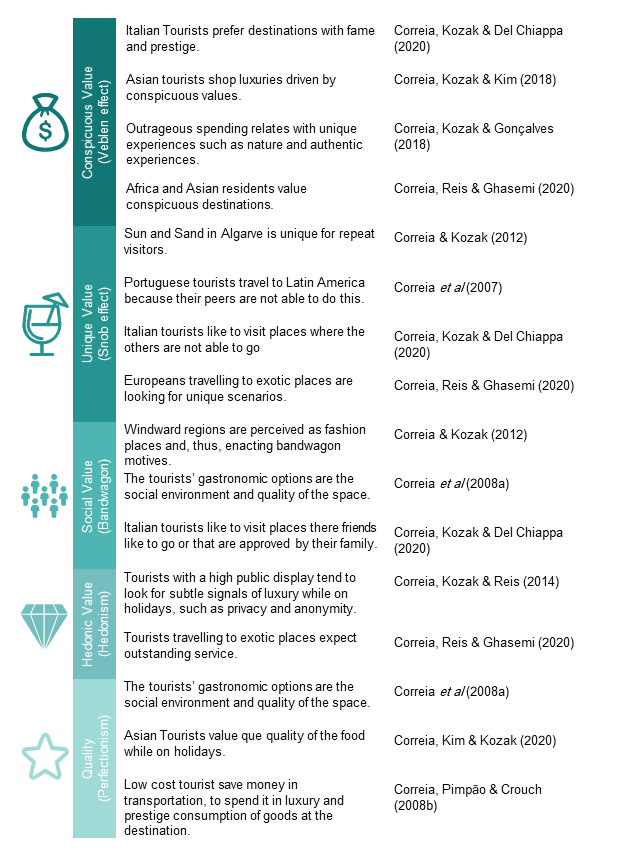

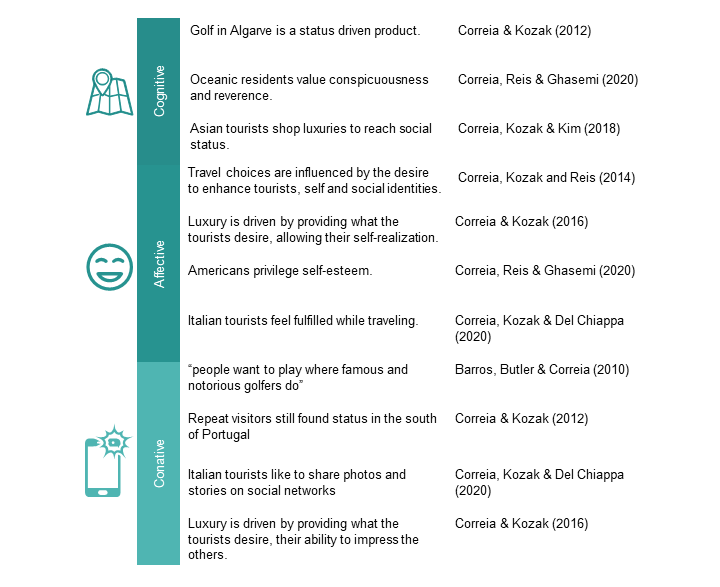

The definition of luxury was tested in different destinations, tourism experiences and within tourists of different nationalities. Until now my team tested antecedents and consequents of luxury tourism in Golf, shopping tourism, gastronomy tourism, and sun and sea tourism. At the level of destinations, the model was tested in Algarve, Italy, Europe, Hong Kong and Latin America. At the market segments level, the model was tested with celebrities, low-cost tourists, golf tourists, domestic tourists and repeat tourists. Nationalities covered in our research are in the five continents, but still need to be enlarged. The contributions to define antecedents and consequents are in figure 3 and 4.

Correia and Kozak (2012) conclude that, in the south of Portugal, golf is a status driven product, sun and sand a snob one, whereas windward regions are perceived as fashion places and, thus, enacting bandwagon motives. Correia, Kozak and Reis (2014) point out that travel choices are influenced by the desire to enhance tourists‘ self and social identities. This research, that analyses tourism choices of Portuguese celebrities, shows that tourists with a high public display tend to look for subtle signals of luxury while on holidays, such as privacy and anonymity. Portuguese tourists highlight uniqueness and social value as the essential conditions to influence decisions to travel to Latin America (Correia et al., 2007).

Research about golf tourist behaviour demonstrates that players are not driven by motivations related to the game, but, instead, players are motivated primarily by the social aspects of playing golf in the Algarve: “people want to play where famous and notorious tourists do” (Barros, Butler and Correia, 2010). Further, the tourists’ gastronomic options are the social environment and quality of the space (Correia et al., 2008a). Finally, research about decision-making processes points out that, despite the fact that most of tourists travel to Algarve by low-cost flight companies, their behaviour responds to the social stimulus. Once they save money in transportation, they can spend it in luxury and prestige consumption of goods at the destination (Correia, Pimpão and Crouch, 2008). Additionally, repeat visitors still found status in the south of Portugal (Correia and Kozak, 2012).

In Italy contexts, Correia, Kozak, and Del Chiappa (2020), prove that luxury meaning arose on social values, with conspicuousness and uniqueness being the antecedents to reach status, self-esteem and public display. Correia, Kozak and Kim (2018) state that, in Asian contexts, luxury shopping is driven by conspicuous values, social status and the need to conform with the others (bandwagon effect). The individual dimension was also emphasized by Correia and Kozak (2016) that argued that luxury is driven by providing what the tourists desire, allowing their self-realization and their ability to impress the others.

In the same vein, Correia, Kozak and Gonçalves (2018) prove that outrageous spending relates with unique experiences, most of them related with nature and authentic experiences. These conclusions were also evident with celebrities living in Portugal, who perceived luxury as the possibility of being unknown and spending quality time with their families and friends (Correia, Kozak and Reis, 2014). More recently, Correia, Reis and Ghasemi (2020) prove that the measurement of luxury aesthetics is also an important dimension to attain luxury to the destinations.

To enrich the luxury meaning, content analysis was performed by my team, reaching thorough meanings, as illustrated in figure 5.

4. Luxury Meanings

The luxury meanings were mostly depicted by asking tourists if they have had a luxury experience and how they describe this experience and how they define a luxury experience. These groups of open hand questions were collected to attain significance the scale items. Figure 5 show some of the meanings collected. The words used suggest that luxury is a superlative experience that relies on comfort, happiness, service, reverence, scenario (striking an breath-taking), privacy and personalization of the service.

Conclusions

Our contribution outlines values that rely on the private and exclusive settings where family and friends are allowed but, mass tourism is to be avoided. From the research we did till now it is possible to conclude that luxury is subjective and tangible:

Subjective:

Luxury relies on superlative and memorable experiences that are irrespective of the price, as such a hedonic experience.

Luxury is a unique experience to share or to differentiate from the others but always to gain status within peers yet driven by social value.

Luxury is our way to be pampered and to enact self-esteem.

Tangible:

Luxury is also breathtaking scenarios, outrageous decorations and personalized services, yet quality and aesthetics defines luxury.

Overall:

Luxury is a multidimensional concept that could be far apart from money and lavish behaviours. This concept comprises social, individual and attributes of the tourism experience that all combined give to the tourist a sense of pleasure and fulfilment. Riley (1995) suggests that luxury tourism depends more on the manner of travelling than to where you travel. Now we would suggest that luxury tourism is subjective and depends mostly on how tourists feel, travel and behave more that to where they travel.

Luxury tourists have the propensity to spend more while on holidays than the common herds, although the real meaning of luxury is still an issue that deserves more and more research, as reality is dynamic and very subjective.

Written by Antonia Correia, University of Algarve, Portugal

Read Antonia’s letter to future generations of tourism researchers

References

Barros, C .P., Butler, R., & Correia, A. (2010). The length of stay of golf tourism: A survival analysis. Tourism management, 31(1), 13-21.

Bentham, J. (1789) reprint in 1988. The Principles of Morals and Legislation. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books.

Correia, A. (2009). Luxury tourism, habilitation lesson, University of Algarve, unpublished.

Correia, A., & Kozak, M. (2012). Exploring prestige and status on domestic destinations: The case of Algarve. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(4), 1951-1967.

Correia, A., & Kozak, M. (2016). Tourists’ shopping experiences at street markets: Cross-country research. Tourism Management, 56, 85-95.

Correia, A., & Moital, M. (2009). Antecedents and consequences of prestige motivation in tourism: An expectancy-value motivation. Handbook of Tourist Behaviour: Theory and Practice, 16-34.

Correia, A., Kim, S., & Kozak, M. (2020). Gastronomy experiential traits and their effects on intentions for recommendation: A fuzzy set approach. International Journal of Tourism Research, 22(3), 351-363.

Correia, A., Kozak, M., & Del Chiappa, G. (2020). Examining the meaning of luxury in tourism: a mixed-method approach. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(8), 952-970.

Correia, A., Kozak, M., & Gonçalves, F. F. (2018). Why do tourists spend extravagantly in Portugal? A binary logistic regression by quartiles. Tourism Planning & Development, 15(4), 458-472.

Correia, A., Kozak, M., & Kim, S. (2018). Luxury shopping orientations of mainland Chinese tourists in Hong Kong: Their shopping destination. Tourism Economics, 24(1), 92-108.

Correia, A., Kozak, M., & Reis, H. (2014). Luxury Tourists: Celebrities’ Perspectives. In Tourists’ Perceptions and Assessments. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Correia, A., Moital, M., Da Costa, C. F., & Peres, R. (2008a). The determinants of gastronomic tourists’ satisfaction: a second‐order factor analysis. Journal of Foodservice, 19(3), 164-176.

Correia, A., Pimpao, A., & Crouch, G. (2008b). Perceived risk and novelty-seeking behavior: The case of tourists on low-cost travel in Algarve (Portugal). In Advances in culture, tourism and hospitality research. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Correia, A., Reis, H. & Ghasemi, V. (2020). Tourism luxury values: a global approach. In P. Pearce & A. Correia (Eds.) Tourism’s New Markets – Drivers, details and directions. http://dx.doi.org/10.23912/9781911635628-4294

Correia, A., Santos, C. M., & Barros, C. P. (2007). Tourism in Latin America a choice analysis. Annals of Tourism Research, 34(3), 610-629.

Duesenberry, J. (1949). Income, Savings and the Theory of Consumer Behaviour, Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

Hovland, C. I., & Rosenberg, M. J. (1960). Attitude organization and change: An analysis of consistency among attitude components (Vol. 176). New Haven, Yale UP.

Keynes, J. M. (1930). The general theory of employment, interest, and money. London: Macmillan.

Leibenstein, H. (1950). Bandwagon, Snob, and Veblen Effects in the Theory of Consumers’ Demand. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 64 (May): 183-207.

Mandeville, B. (1714). The fable of Bees or private vices, public benefits. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Marshal, A. (1890). Principles of Economics, London: Macmillan.

Mason, R. (1998). Conspicuous Consumption: A Study of Exceptional Consumer Behaviour. St. Martin Press, New York.

Mill, Stuart J. (1848). Principles of Political Economy, reprinted in J.F.Robson (ed.) (1965), Toronto: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Rae, J. (1834). Statement of some new principles on the subject of political economy: exposing the fallacies of the system of free trade, and of some other doctrines maintained in the” Wealth of nations.”. Boston: Hilliard, Gray.

Riley, R. W. (1995). Prestige-worthy tourism behavior. Annals of Tourism Research, 22(3), 630-649.

Samuelson, Paul (1949). Foundations of Economic Analysis, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Smith, A. 1759. The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Indianapolis, Liberty Classics

Veblen, T. B. (1902). The Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study of Institutions. London: Unwin Books, 1970.

Vigneron, F., & Johnson, L. W. (1999). A review and a conceptual framework of prestige-seeking consumer behaviour. Academy of Marketing Science Review, 9(1), 1-14.

Image descriptions

Figure 1 image description: Chronology of luxury research. Primitive Era: Women and slaves. Roman Empire: Conspicuous consumption is restricted by law. Mercantilists: Conspicuous consumption is offensive and against the interest of nations. Until the XVII century: Conspicuous consumption allowed to aristocracy. Until the mid-1700s: Some economists recognized that vanity (Adam Smith, 1759) and interpersonal factors (Bentham, 1789) may influence consumer behaviour and started questioning the impact of this consumption on the economy. XVIII century: Conspicuous consumption is tolerated (New bourgeoisies). Neoclassical theorists (XIX century): Conspicuous consumption is widely recognized. Marshall (1890) states that part of the conspicuous consumption is necessary. Rae (1834) and Suart Mill (1848) argue that luxury is the aim to have what others cannot have. Modern capitalist (XIX-XX century): Social power and status are driven by buying very expensive products. XX century: From the 1930s conspicuous consumption is widely accepted (Keynes, 1930; Duesenberry, 1949; Samuelson, 1949; Leibenstein, 1950) but remain unstudied. Duesenberry introduced the demonstration effect and Leibenstein the bandwagon, snob and veblen effects. By the 1990s Veblen effect was finally accepted and studied by economists. Post-modern Era: Prestige for the masses is given by image and experiences.

Figure 2 image description: Figure showing the luxury model. The antecedents are: perceived conspicuous value, perceived unique value, perceived social value, perceived hedonic value, and perceived quality value. The perceived importance of prestige (Valence) is linked to the prestige perceived performance (instrumentality) and the prestige perceived performance (expectancy). The consequences are cognitive (acceptance by others, reverence by others, and status); affective (self-esteem); and conative (intention to travel, travel propensity, word-of mouth, and public display of souvenirs).

Figure 3 image description: Contributions to define antecedents of luxury.

| [Conspicuous value (Veblen effect)] Italian Tourists prefer destinations with fame and prestige. | Correia, Kozak & Del Chiappa (2020) |

| [Conspicuous value (Veblen effect)] Asian tourists shop luxuries driven by conspicuous values. | Correia, Kozak & Kim (2018) |

| [Conspicuous value (Veblen effect)] Outrageous spending relates with unique experiences such as nature and authentic experiences. | Correia, Kozak & Gonçalves (2018) |

| [Conspicuous value (Veblen effect)] Africa and Asian residents value conspicuous destinations. | Correia, Reis & Ghasemi (2020) |

| [Unique value (Snob effect)] Sun and Sand in Algarve is unique for repeat visitors. | Correia & Kozak (2012) |

| [Unique value (Snob effect)] Portuguese tourists travel to Latin America because their peers are not able to do this. | Correia et al (2007) |

| [Unique value (Snob effect)] Italian tourists like to visit places where the others are not able to go | Correia, Kozak & Del Chiappa (2020) |

| [Unique value (Snob effect)] Europeans travelling to exotic places are looking for unique scenarios. | Correia, Reis & Ghasemi (2020) |

| [Social value (Bandwagon)] Windward regions are perceived as fashion places and, thus, enacting bandwagon motives. | Correia & Kozak (2012) |

| [Social value (Bandwagon)] The tourists’ gastronomic options are the social environment and quality of the space. | Correia et al (2008a) |

| [Social value (Bandwagon)] Italian tourists like to visit places there friends like to go or that are approved by their family. | Correia, Kozak & Del Chiappa (2020) |

| [Hedonic value (Hedonism)] Tourists with a high public display tend to look for subtle signals of luxury while on holidays, such as privacy and anonymity. | Correia, Kozak & Reis (2014) |

| [Hedonic value (Hedonism)] Tourists travelling to exotic places expect outstanding service. | Correia, Reis & Ghasemi (2020) |

| [Quality (Perfectionism)] The tourists’ gastronomic options are the social environment and quality of the space. | Correia et al (2008a) |

| [Quality (Perfectionism)] Asian Tourists value que quality of the food while on holidays. | Correia, Kim & Kozak (2020) |

| Low cost tourist save money in transportation, to spend it in luxury and prestige consumption of goods at the destination. | Correia, Pimpão & Crouch (2008b) |

Figure 4 image description: Contributions to define consequents of luxury.

| [Cognitive] Golf in Algarve is a status driven product. | Correia & Kozak (2012) |

| [Cognitive] Oceanic residents value conspicuousness and reverence. | Correia, Reis & Ghasemi (2020) |

| [Cognitive] Asian tourists shop luxuries to reach social status. | Correia, Kozak & Kim (2018) |

| [Cognitive] Travel choices are influenced by the desire to enhance tourists, self and social identities. | Correia, Kozak and Reis (2014) |

| [Cognitive] Luxury is driven by providing what the tourists desire, allowing their self-realization. | Correia & Kozak (2016) |

| [Cognitive] Americans privilege self-esteem. | Correia, Reis & Ghasemi (2020) |

| [Cognitive] Italian tourists feel fulfilled while traveling. | Correia, Kozak & Del Chiappa (2020) |

| [Conative] “people want to play where famous and notorious golfers do” | Barros, Butler & Correia (2010) |

| [Conative] Repeat visitors still found status in the south of Portugal | Correia & Kozak (2012) |

| [Conative] Italian tourists like to share photos and stories on social networks | Correia, Kozak & Del Chiappa (2020) |

| [Conative] Luxury is driven by providing what the tourists desire, their ability to impress the others. | Correia & Kozak (2016) |

Figure 5 image description: Content analysis of luxury meanings.

| [Conspicuous value (Veblen effect)] All the comfort I could wish and without any constraints on how to spend …limousine…and everything one could need to enjoy it

Correia, Kozak & Del Chiappa (2020) |

| [Conspicuous value (Veblen effect)] The most luxury tourism experience that I had was when I traveled to Macao with my partner for a trip that was generously paid for us. I think this trip was luxury because we stayed in expensive hotels, the ticket to the best and also expensive shows were bought for us and we were taken care of for almost everything that we needed

Correia, Reis & Ghasemi (2020) |

| [Unique value (Snob effect)] Transcendence. A manner of going out of our normal way of being in our daily lives

Correia, Kozak & Reis (2014) |

| [Unique value (Snob effect)] Anticipatory and personalized guest experience; curated around my needs and expectations; services and experiences that are not available or accessible to the mass market

Correia, Reis & Ghasemi (2020) |

| [Unique value (Snob effect)] A place where I won’t to be recognized

Correia, Kozak & Reis (2014) |

| [Social value (Bandwagon)] My family and friends are happy for me… They think that I deserve it after having worked hard as I used to do

Correia, Kozak & Del Chiappa (2020) |

| [Social value (Bandwagon)] My friends and family found such experience cool and they were happy for me

Correia, Reis & Ghasemi (2020) |

| [Hedonic value (Hedonism)] Striking, breathtaking scenery, staying at a very comfortable …maybe in a palace

Correia, Kozak & Reis (2014) |

| [Hedonic value (Hedonism)] My husband and I were in a trip to Tioman Island in Malaysia. We stayed for 5 days in 5-star resort by beach in the Island. We did snorkelling, we ate very delicious seafood. We get relaxing most of the time. We had unforgotten times there

Correia, Reis & Ghasemi (2020) |

| [Quality (Perfectionsim)] My luxury experience was in a 7 star hotel all the time being served and revered and having the possibility of experiencing a lot of comfort and services

Correia, Kozak & Del Chiappa (2020) |

| [Quality (Perfectionsim)] Those experiences were luxury due the offer of services, design, comfort, location

Correia, Reis & Ghasemi (2020) |

| [Cognitive] Enjoy a stay where there are people with a high social status, being served and revered

Correia, Kozak & Del Chiappa (2020) |

| [Affective] I was experiencing relaxation and intimacy within the couple, and mixed these moments with some excursions that allow you to be in touch with the local culture and gastronomy

Correia, Kozak & Del Chiappa (2020) |

| [Conative] I would engage on some sort of photography work and travel writing in order to share it with my friends

Correia, Kozak & Reis (2014) |