40 Peace, Conflict, Tourism and Other Things in Between

Anna Farmaki

I grew up in Cyprus, a small island located in the eastern part of the Mediterranean. Cyprus is known for three things. First, it is recognised as a tourist destination boasting beautiful beaches, a warm climate and a rich culture that spans 10000 years of history. Second, the island became known in recent years as a potential tax haven, a credible European Union and Eurozone jurisdiction offering financial services and business activities. Third, it is often regarded as the place hosting one of the world’s most intractable conflicts that rightfully gained the nickname “the graveyard of diplomats”. The so-called “Cyprus problem” refers to the ongoing dispute between the island’s two main communities, the Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots; a dispute that has gone for decades for reasons that are not the focus of this contribution and will, therefore, not be discussed here. Yet, the Cyprus dispute has shaped every facet of life for its people. In a way, you may say that Cypriots grew up in conflict and, even though there is currently no active violence on the island, residues of the dispute may be found in education, the media, politics and the economy remining us that it is still persistent.

Unsurprisingly, when I stumbled on the peace-through-tourism idea in the early stages of my academic career I was immediately intrigued. In essence, the peace-through-tourism tenet suggests that tourism may contribute to the peacebuilding efforts of communities that have experienced conflict as travel-induced contact improves people’s perceptions, attitudes and understanding of one another, harmonizing the relations between countries (D’ Amore, 1988; Higgins-Desbiolles, 2003; Kim et al., 2007). The word ‘peace’ is one that I heard since a young age as, alongside the word ‘conflict’, it has found its way in Cypriots’ daily lexicon. While I didn’t know what peace necessarily felt like, I knew what conflict was. And the more I read about the potential role of tourism in peacebuilding, the more I realised that conflict was largely overlooked in the peace-through-tourism literature. In fact, I felt that the peace-through-tourism narrative was romanticized in the relevant discourse and several important aspects pertaining to conflict, peace and tourism were ignored. It was this gap in the literature that led me to embark on a research journey with the aim of understanding the interrelationships of the constructs of conflict, peace and tourism and the implications of these for the peace-through-tourism notion. To be honest, that was not easy to do as I had to read and understand theories from ‘foreign’ fields. I had a marketing background and much of my past research focused on the management and consumption aspects of tourism. So, the politics of peace and conflict were unfamiliar territory to me.

Nonetheless, the study of these theories began to provide shed light and reveal several omissions within the peace-through-tourism literature. To begin with, I realised that much of previous research was descriptive in nature lacking theoretical underpinning from the political science and/or international relations fields. Studies advocating the peace-through-tourism tenet often presented the concept of peace simplistically, failing to acknowledge that there are different forms of peace. A widely used conceptualization of peace is that offered by Galtung (1964) who distinguished between negative peace, namely the absence of violence, and positive peace which refers to the absence of violence and the presence of justice, cooperation, equality, freedom of actions and pluralism. Positive peace has, thus, a long-term perspective of transforming the conflict context by addressing the causes of the conflict and ensuring that violence reoccurrence is unlikely (Farmaki and Stergiou, 2021). Peace and conflict are two sides of the same coin; hence, one cannot be addressed without a consideration of the other. However, past studies largely ignored the influence that the nature and duration of conflict has on peacebuilding. What political science literature informs us is that conflict may (re)emerge as a result of macro or micro level reasons or a combination of both. Generally speaking, conflict may occur due to: a) ethnic divisions in a society, b) economic factors and resource competition and c) political and institutional factors. While issues of dispute may be present, for a conflict to emerge a mobilization strategy on behalf of political actors and a series of events are required to onset and sustain a conflict (Dessler, 1994). As such, conflicts have escalation and de-escalation periods as they are dynamic in nature; nonetheless, it is generally agreed that the longer a conflict lasts the harder it is to restore peace as it may yield a permanent negative effect on people’s perceptions and attitudes.

This brings me to the second research gap evident in the peace-through-tourism literature. Many of the peace-through-tourism studies published yielded inconclusive results over the contributory role of tourism to peacebuilding. This is somewhat expected considering that much of past research draws from case studies, limiting the generalization effect that credits the validity of their findings. Every case studied has a specific conflict context and duration that influence the degree to which peace can be restored either in general or through tourism. What’s more, these studies rely on the contact hypothesis to deduce conclusions over tourism’s role as an agent of peace. The contact hypothesis suggests that through travel people interact and gain a mutual appreciation of one another; thus, positioning tourism as a track two diplomacy activity (Kim and Crompton, 1990). Yet, tourism is more than that. It is a political tool and an economic industry that causes conflicts and deepens inequalities due to its capitalistic orientation (Bianchi, 2018). Therefore, extant literature has simplified the role of tourism as well as its structure which impacts the nature of contact occurring. Indeed, most past studies focused on pre-visit and post-visit comparisons of visitors’ perceptions of the hostile community, ignoring that the nature of mass tourism frequently limits meaningful contact between visitors and the host community (Farmaki, 2017). This presents the third gap in the peace-through-tourism literature.

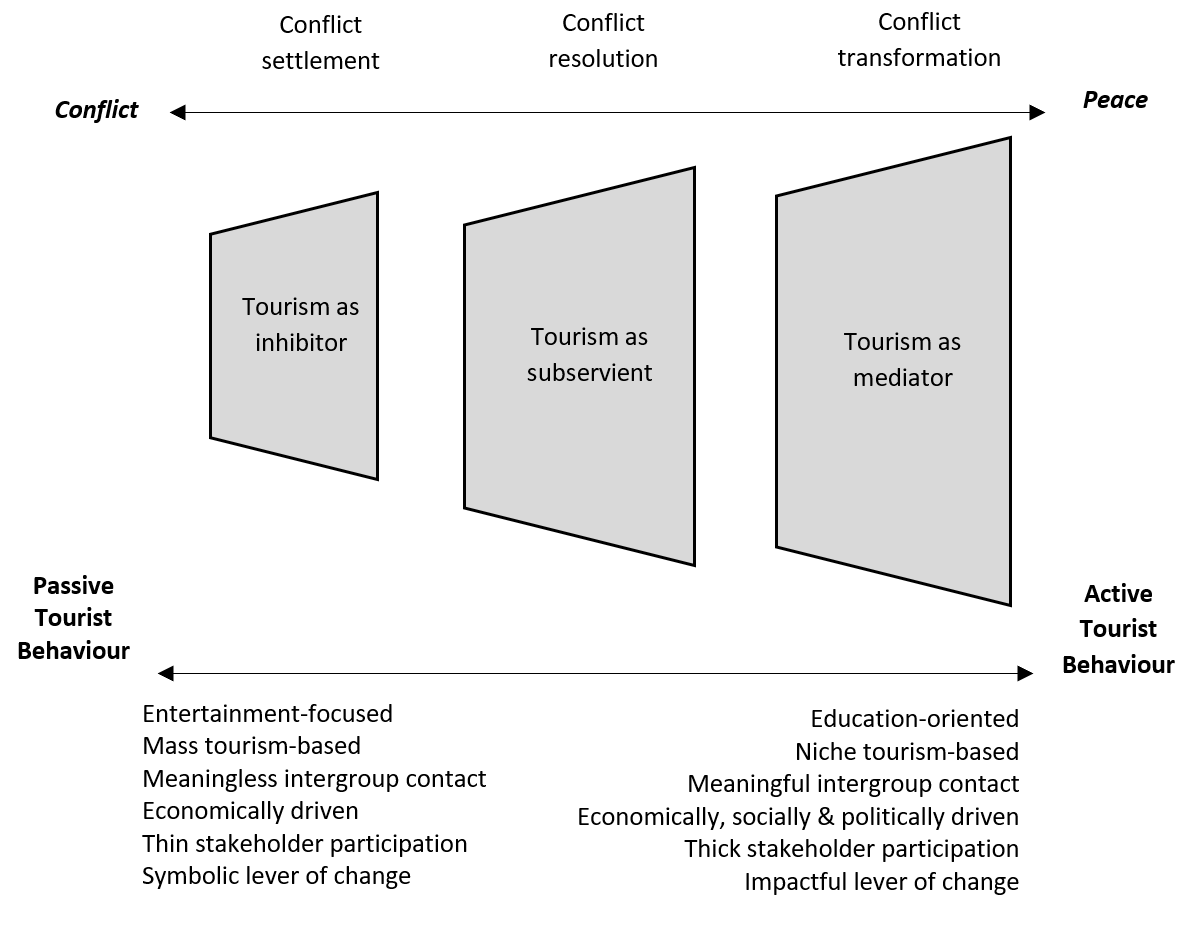

Consequently, to illuminate understanding of the peace-though-tourism tenet and enable the research agenda to progress, I contributed a framework known as peace-through-tourism continuum (Figure 1).

As proposed by the framework, tourism may act as an inhibitor of peace, restricting the contributory effect to reconciliation by fostering competition that may lead to conflict re-emergence. This is most likely to be the case when a destination relies on mass leisure tourism that promotes a passive form of contact. Therefore, even though a conflict may be settled it does not necessarily mean that the tourism activity will contribute to eliminating its causes, leaving the door open for conflict to re-emerge. Tourism may also become a subservient of peace, particularly if the right management mechanisms are not put into place. In such cases, tourism may substitute reconciliation, particularly where tourism represents an important economic activity as behaviour may be triggered by a service compliance and conformity to expectations between the visitors and the host community. Such passive form of travel will neither reduce socio-psychological gaps nor enhance social integration between members of divided communities. Last, tourism may act as a mediator of peace as various alternative forms of tourism that are education-oriented may encourage meaningful contact between divided communities and make an impact on efforts to transform the conflict context and plant the seeds for a sustainable form of peace to grow. After all, several studies offer hopeful glimpses of tourism’s potential such as enhancing forgiveness between divided communities (Carbone, 2021). Therefore, tourism’s role to peace is multifaceted; it can break barriers and become a synergetic factor but it can also become a dividing one.

By writing this contribution, I’ve been given an opportunity to reflect on my own research and on others who published on peace-through-tourism. My conclusion is that it is naively simple to suggest that tourism can bring peace. It is also cynical to suggest that it doesn’t. Who can say with certainty that tourism cannot change the world for the better and help rebuild what is broken? Imagine if it could! Failure to do so is defeat, like admitting that a disease has no cure.

I, therefore, urge the readers to continue researching the peace, conflict and tourism nexus. As a person who has lived in conflict, I’d say the pursuit of peace through any means is worthwhile.

Written by Anna Farnaki, Cyprus University of Technology, Cyprus

References

Bianchi, R. (2018). The political economy of tourism development: A critical review. Annals of Tourism Research, 70, 88-102.

Carbone, F. (2021). “Don’t look back in anger”. War museums’ role in the post conflict tourism-peace nexus. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1-19.

D’Amore, L. J. (1988). Tourism—A vital force for peace. Tourism Management, 9(2), 151-154.

Dessler, D. (1994). How to sort causes in the study of environmental change and violent conflict. Environment, Poverty, Conflict, Oslo: International Peace Research Institute, 91-112.

Farmaki, A. (2017). The tourism and peace nexus. Tourism Management, 59, 528-540.

Farmaki, A., & Stergiou, D. (2021). Peace and tourism: Bridging the gap through justice. Peace & Change.

Galtung, J. (1964). A structural theory of aggression. Journal of Peace Research, 1(2), 95-119.

Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2003). Reconciliation tourism: Tourism healing divided societies!. Tourism Recreation Research, 28(3), 35-44.

Kim, Y. K., & Crompton, J. L. (1990). Role of tourism in unifying the two Koreas. Annals of Tourism Research, 17(3), 353-366.

Kim, S. S., Prideaux, B., & Prideaux, J. (2007). Using tourism to promote peace on the Korean Peninsula. Annals of Tourism Research, 34(2), 291-309.