29 Reflections on Place, Identity and Tourism Research (And Finding One’s Place in the World)

Suzanne de la Barre

My input to this collection on women’s contributions to tourism research takes the form of what I would loosely call a “research note”. Much of my research is influenced by an almost life-long love affair with place and identity. My submission is a response to the generous invitation made to women tourism researchers, and the editorial guidelines that encourage contributors to voice their submissions in whatever way they want to. Consequently, I’ve been drawn to frame by contribution through select biographical details (things I’ve done and experienced in my life). Then combine the ruminations-like exploration in relation to some epistemology-connected considerations (e.g., how has my knowledge been acquired?). To some degree, then, what follows is influenced by critical perspectives on the human element in (tourism) knowledge production, and the way that autobiography can be employed as a means to shape what tourism scholars do research on and why (see for instance Pearce, 2015). By extension, it is informed by contemplations on the role of the researcher’s position in their research, or reflexivity (Phillimore & Goodson, 2004 provide examples with insights that have guided my development as a scholar).

I have struggled with articulating what is ‘my contribution to tourism research’ while writing this submission. I’m not alone. Like others in this volume – based on my read of some of the chapters already available – my ability to put my finger on what my contribution might be is tainted by the ‘imposter syndrome’ and the anxiety-inducing self-questioning that accompanies that ailment (e.g., is my work really worthy of inclusion in this volume?). My struggle is also deployed by the form of contribution I have designed – autobiographical, reflexive, and accompanied by the fear that the shape of this contribution will be perceived as self-indulgence and self-promotion. Yet, at every turn, and in the spirit of the aims and objectives of this volume, I remind myself that there are too few women voices in the tourism academe (Still? Why? How?). So, with that preamble, let’s start with a beginning.

It was not just the stroppy searching for belonging of an out of place adolescent; it was my quest for adventure and self-knowledge. A telling if awkward poem I wrote for my parents at age 18 reads:

I want to be me.

I want to do the things I’ve dreamt of.

I want to join a circus in Russia,

be a spy,

live in Africa.

I have something to find,

I don’t know where to look,

but it’s out there!

For some, the decision to become an ‘academic’ is a well-thought out and intentional trajectory. For me, academia is a place I’ve ‘accidentally’ landed and mostly paused in across my lifespan (BA Human Geography, 1984; Master in Environmental Studies, 1991; PhD, 2009). My university education has had a superpower-like quality that reflects back to me my many life journeys and the passions that emerged or deepened along the way.

Undeniably, it’s a not-uncommon-story that my foray into tourism as a domain of study began unwittingly with my own travel experiences. Through my adventures I discovered the rich attributes travel delivered to emotional and intellectual reflections on who I am (identity), and what supports my sense of belonging, or not (place). Those considerations, graciously, though sometimes begrudgingly, led me to interrogate the privileges that shape my life: that is the many and intersectional advantages that include those I was born into, unintentionally or intentionally grew into, and even those I may have aspired to but never achieved; for better or worse.

The first realization that drove what would become my future academic pre-dispositions was the simple if not immediately obvious fact that travel, as I was experiencing it, was an opportunity enjoyed by few citizens of this planet. I can clearly remember the steps that my 24 year-old self was sitting on with Yugoslavian student companions I met while camping in my $20 Canadian Tire pup-tent on the holiday island of Hvar. This was in the few years leading up to the conflict that dismantled the former nation known as Yugoslavia. On those steps was offered to me a significant and life-changing perspective: I had met my companions in their country, and they had not the means to imagine how they might have met me in my own country, Canada. I thought of myself as a ‘poor’ backpacker, yet it became clear that what I was enjoying was the exceptional privilege that allowed me the ability to travel and have the experience of meeting people in their far-away places, and discovering along the way something about those places. I connect these early contemplations to discussions found in what we now know as ‘critical mobilities’ (Torabian & Mair, 2021).

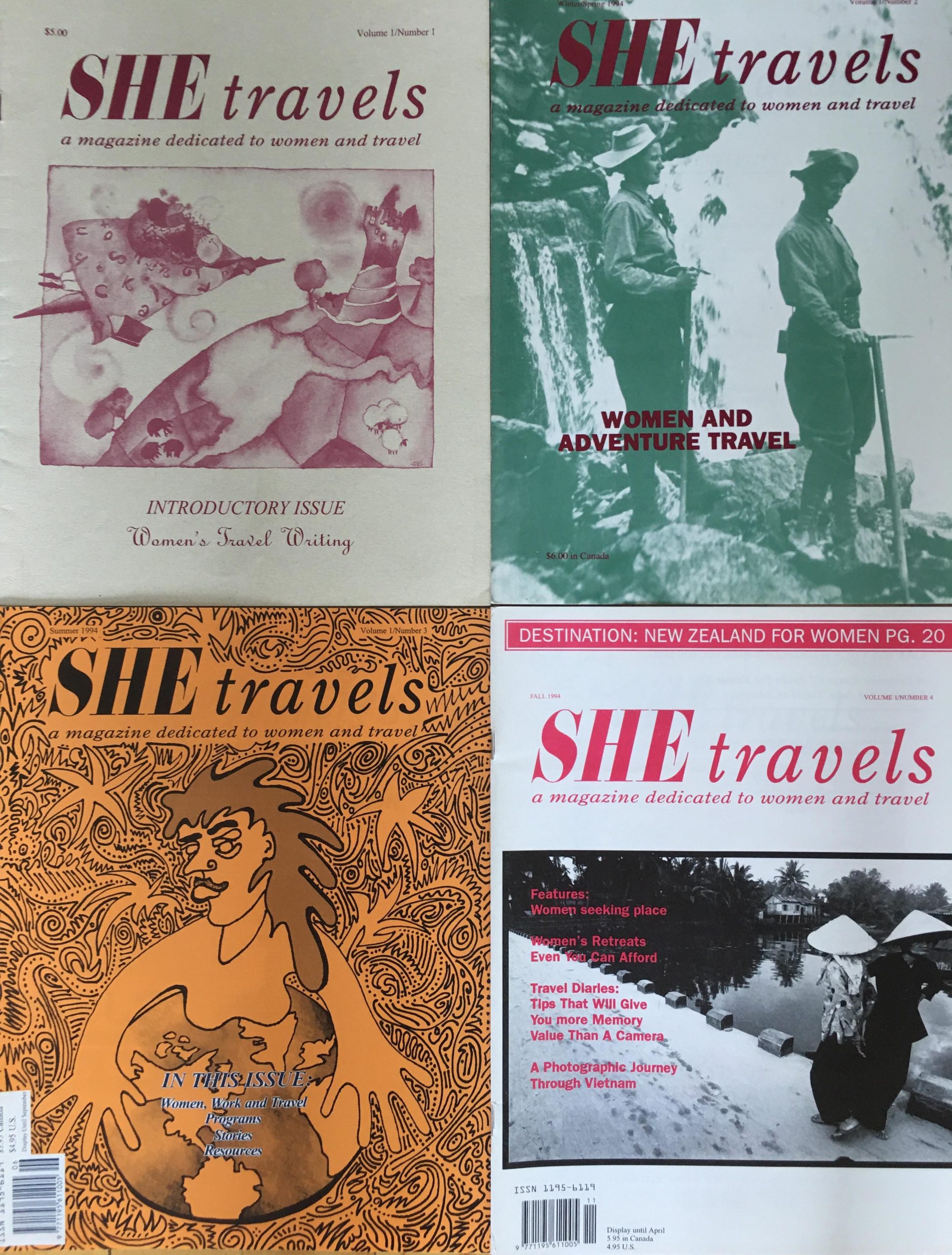

I did not know it then, but my first travel-inspired career began on those steps. SHE travels: a magazine dedicated to women and travel was a seed I planted during that inaugural 9-month backpacking voyage. My publishing company Hit the Road Press (which was almost named On Itchy Feet Press!) nurtured a need to investigate travel in a critical manner. From 1992 to 1994 I published and co-edited SHE travels with long-time bestie Elizabeth Brûlé (now AKA Dr. Elizabeth Brûlé, Queen’s University). The more-than-zine and much-less-than-academic-journal was co-produced from my wood-stove-only-heated-no-running-water-cabin-in-the-woods (yes, I had electricity) an hour south of Whitehorse (Yukon), and Liz working from her metropolis located home in Toronto. Our subscription service circulation was a resource and labour intensive initiative. It helped extend our lifespan that by issue #3 we were members of the Canadian Magazine and Publishers Association (now Magazines Canada) which also distributed our publication to 50+ bookstores across Canada.

As editors, our preferred critical lens was to examine women’s travel through our experience as avid women travellers. We informed this lens with the application of the feminist analytical devices we were acquainted with at the time. In my bookshelf still today are the nostalgic remnants of that era. To name a few: Jaggar & Bordo (1989), Nicholson (1990), Ramazanoglu (1989), and Weedon (1987). Our first issue editorial provides some insight into our motivation and mission:

Experience necessitates not only the practical but the contemplative. Exploring women’s different experiences and reasons for travel allows for an understanding of their political and social circumstances. This is the focus of SHE travels … SHE travels is designed as a forum for women’s voices, concerns and interests. This magazine promises to address women’s travel experiences as well as providing for literature and guide book review, culinary insights, equipment needs, networking opportunities and solo travel. Ultimately, it is our hope that SHE travels will inspire women to challenge conventional definitions of travel and share their insights with other women.

Our four issues over two years shared stories about women travelling alone or with companions, travel poetry, photo journals, and contemplations on mobilities of all sorts, including the impacts of moving around too much. We engaged with realizations women made about inequities and privilege through their travel experiences in our editorial purpose. Gender was conceptualized as binary, as was the pre-dominant if increasingly challenged discourse of the time. Still, our three-times a year publication was more inspired reflection than outright critical analysis. We mostly published prose that kept us poor but fulfilled; for a while anyways. Sadly, our magazine initiative occurred in the Yukon’s pre-internet world, and our fax bills finally did us in.

It is with our final issue’s editorial that I can see a window into my at-the-time-unknown-to-me future academic career:

Despite historical pre-occupations with the effects of place on people, there has been a strong tendency to see women as linked to family. Consequently, it has meant that women’s bond to land/place has been seen as either secondary or it has been overlooked completely … This issue presents the stories of women who have reflected on the influence of place and the role it has played in their lives.

…

Metaphorically, travelling also reflects upon an internal process: one whereby the traveller can take a voyage inside one’s self. This personal experience is as powerful as is the experience of finding your way through a new land and visiting new peoples. It is hoped that this issue will inspire some thoughts on how place shapes the lives of women. It is also meant to acknowledge how travel is often as much about gaining perspective on where we come from, as it is about where we are going to.

Reading our editorial now, I find myself surprised that my place and identity interests were already obvious so many years before my doctoral studies were even contemplated. It seems somehow worth mentioning that while the magazine and its gender focus inspired some of my later academic purpose, with the exception of a co-edited special issue of Téoros, a French language peer review publication of the Université du Québec à Montréal (Antomarchi & de la Barre, 2010), gender was for the most part explored ‘incompletely’. In fact, it constituted by and large enquiry that never made it past the conference presentation stage (de la Barre, 1994; de la Barre, 2011; de la Barre & Sandberg, 2013). What I surmise from this turn of events is the value of feminist analysis as a ‘transferable skill’ for understanding how systems of oppression/empowerment work. Among other things, I have used those critical analysis skills to better understand movement and mobility, and applied them to the practices involved with supporting place-based community-economic development.

From 1997 to 1999, a few years after SHE travels came to an end, and while working in a participatory methodologies unit with an NGO in Malawi, my understanding about who gets to move around the globe by choice was corroborated. This time my reflections were enhanced by my increased life experience and maturity, both personal and political. Through observation, conversation and my day-to-day lived experience with my Malawian colleagues and friends, I was drawn to revitalized and newly informed questions: What was I doing in Malawi? What even made it possible for me to be there? And what would be (could be) my useful contribution to Malawians enhanced well-being and empowerment?(!). I left Malawi with a much more robust appreciation for the way ideological and other traps (continue to) fuel colonization-infused efforts in all parts of the world. The latter includes here at home in Canada when considering Turtle Island’s original Indigenous people, and the systemic challenges they face that inhibit their emancipation, land-based relationships, and their social/cultural and economic well-being. Less attention has been paid to the way colonization and its legacies have detrimentally impacted opportunities for greater reciprocal and mutually supportive relationships between settlers and contemporary newcomers to Canada, and the original peoples of this land. Through grieving the missed opportunities to better know and enjoy one another, I’m also drawn to finding ways I can influence change.

As capstone reinforcement to my growing awareness and politicization, my return to Canada after two years in Africa introduced me to a new-for-me category of ‘travellers’. My work as an Ottawa-based program manager with WUSC’s Student Refugee Program left little doubt, and crystallized for me the nature and reach of my privilege (wusc.ca and https://wusc.ca/what-we-do/#programming-areas). My job required extensive stays in refugee camps in several African countries and Pakistan with the goal of interviewing people whose post-secondary studies had been interrupted by conflicts leading to them becoming refugees. The outcome of my interviews was to determine which potential students could be eligible for a university scholarship at a Canadian university. The way I tell it is that I had the terrible task of playing Gawd. But there were grand rewards to that work: the results of the excruciatingly difficult selection process were that some refugee lives were forever transformed, and mostly in advantageous and life-fulfilling (and sometimes possibly life-giving) ways. I also worked with those selected students when (if) they arrived in Canada. The gratitude they expressed to me for my part in supporting their access to that life-changing opportunity was and remains forever humbling.

Forced migration is surely the epitome of what is human movement. It exists on a point on the ‘mobility paradigm’ as far from the concept of leisure travel and tourism as you can get. And then some.

It was the weight of these diverse experiences that supported the kinds of questions and questioning that shaped my PhD research and the academic career that followed. I gained intimate knowledge of the way place narratives tell stories and illustrate the strong unavoidable dialogue between the ‘where’ and the ‘who’. My doctoral research examined narratives at the nexus of place and identity. My enquiry was applied to diverse forums of resident place expressions and, through interviews with Yukon’s wilderness and cultural tour guides, examined also how place narratives intersected with those employed by and for tourism. Among other things, my findings hinged on interpretations of how our place stories provide rich material to consider how the where/who relationship intrinsically – though not deterministically – mutually shape one another (de la Barre, 2009).

Post-PhD completion, my ‘findings’ continued to evolve. As they should I think, because, in my experience at least, there are few-to-no useful (interpretive?) intellectual endeavours that remain ‘true’ beyond the time it takes for the printer ink to dry on a page. Doreen Massey’s (2005) ‘progressive sense of place’ offered exciting place conceptualization opportunities post-thesis. A progressive sense of place understands space as “open, multiple and relational, unfinished and always becoming, is a prerequisite for history to be open and thus a prerequisite, too, for the possibility of politics” (p. 59). Her ideas enriched my understanding of place/identity and (hopefully) improved upon my ability to reckon with determinisms of all sorts (de la Barre, 2012a). Oh but to find the time to go back to that work yet again! There remain to investigate so many truths, so many fictions … (all of them temporary and sometimes useful lies?).

Significantly, my PhD research brought me back home to the Yukon. Canada’s changing northern regions, often characterized as the remote regions of this country (…but remote for whom?), captured my attention and commitment. I found a way to collapse interests, passion, and purpose with the desire to (finally) make my place at home. With research aimed at better understanding the Canadian north my questions shifted to my local, all the while informed by my experience of and considerations for the global: What does sustainability mean, and for whom is it operationalized? (de la Barre, 2005); and, what can we know about a place as it is expressed and experienced by communities and their residents in relation to the way these expressions are promoted for tourism? (de la Barre, 2012b; de la Barre, 2021; de la Barre & Brouder, 2013). I sought out and committed also to work collaboratively with researchers in other norths who were introduced to me through my two-year post doctorate research at Umeå University in northern Sweden (2010-2012). Together with colleagues from Sweden, Norway, Finland and Iceland we have strived to discover the ever-evolving questions and ephemeral understandings that respond to community and change through the lens of demographic mobility, change and innovation in the sparsely populated world (Carson et al., 2016) and Arctic tourism (Müller et al., 2020; Rantala et al., 2019).

The study of tourism-influenced phenomena has consistently fascinated me and enabled place and identity-encouraged interventions that aim to engage social justice considerations. Certainly, others have more explicitly captured the equity and justice issues involved: Freya Higgens-Desbiolles – a self-described ‘academic heretic’ (this volume) – has, in my opinion, prompted much needed debate in the academe. The possibility of ‘hopeful tourism’ and tourism that supports social justice has coloured my work (Higgens-Desbioles, 2006; Higgins-Desbiolles & Blanchard, 2010; Higgins-Desbiolles & Whyte, 2013), even if cynicism or despair or my perceived inability to creatively engage with it has stymied it. Place and identity research in the present moment in my own country, Canada, is distorted by the systemic and other challenges experienced by Indigenous researchers and the contributions they have not been supported to make. Applied dimensions of identity and place expressed in widespread and failed community-economic development initiatives illustrate what the impacts caused by a lack of diversity in (tourism) research can be; and perhaps more so where ‘authoritative’ research contributions are concerned. That is, what gets researched, published, circulated and welcomed into the debates and discourse in meaningful and impactful ways.

Nonetheless, there is evidence this is changing. Indigenous scholars and researchers are having an impact, and their work is increasingly available for us to engage with. For example, Hilton’s Indigenomics (2021), and tourism-specific Indigenous-authored research and scholarship, for example, Bunten (2010), Bunten & Graburn (2018) and Aikau & Gonzales (2019), to name only a few. Their work clearly suggests that Indigenous-authored contributions stimulate improved and valuable perspectives and understandings – and provide opportunities for the kind of dialogue that builds more meaningful and useful knowledge. Questions I ask myself include: What does this emerging scholarship mean for identity-privileged researchers (settler, male, cisgender, and any privileged identity in relation to the issue under investigation)? Can applying reflexivity and other strategies – for instance, researcher motivation and ability to understand what it means to be on the sidelines of academic knowledge production – influence how identity-privileged researchers engage in research? What choices do identity-privileged researchers need to make with regards to the research they should engage in? What can identity-privileged researchers do to support inclusive research that will positively impact more meaningful knowledge production – not to mention, help them to better engage with the possibility of enriching the lives of those impacted by research? Finally, how can identity-privileged researchers engage with doing research while considering the less-identity privileged ‘marginalized’ researchers who may be better positioned to lead that research in their stead, given the chance? (For related discussions that provide insight into some of these questions see Fullagar & Wilson, 2012; Grimwood et al., 2015 and Grimwood et al. 2019).

This volume and its approach is a breath of fresh air. I extend my gratitude to the editors for inviting me to participate. The exercise of writing this contribution makes me realize more than ever that creating my place in what I assess to be the current distorted research landscape requires my deliberate attention: What can I contribute to place and identity (tourism) research that might add meaningful, life-enhancing, empowerment supporting value to what we know? This question I ask, this time, is not an ‘imposter syndrome’ related conundrum. Rather it is a much needed interrogation that relates to what I embrace as the moral responsibility in my scholarly and ‘real-life’ ambitions; similar in fact to the trajectory that drove the questions that arose from my work in Malawi.

My 18 year old self could not have known that the journey I began so many years ago would be entangled in such a fertile quagmire. Circuses in Russia aside, and I’ll never be a spy, but the spirit of my desired adventure lives on. And tourism scholarship has given me lifelong legs to dance with.

Written by Suzanne de la Barre, Vancouver Island University, Canada

Read Suzanne’s letter to future generations of tourism researchers

References

Aikau, H.K. and Gonzales, V. V. (Eds) (2019). Detours: A Decolonial Guide to Hawai’i. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Antomarchi, V. et de la Barre, S. (2010). Présentation: Tourisme et femmes. TÉOROS, 29(2) 87-92.

Bunten, A.C. (2010). More like ourselves: Indigenous capitalism through tourism. American Indian Quarterly 34(3), 285-311. DOI:10.1353/aiq.0.0119

Bunten, A. C. and Graburn, N. N. (2018). Indigenous Tourism Movements. Toronto: University of Toronto Press

Carson, D.A., Cleary, J., de la Barre, S., Eimermann, M., and Marjavaara, R. (2016). New Mobilities – New Economies? Temporary populations and local innovation capacity in sparsely populated areas. In A. Taylor, D.B. Carson, P. Ensign, L. Huskey, R.O. Rasmussen & G. Eilmsteiner-Saxinger (Eds.), Settlements at the Edge: Remote human settlements in developed nations (pp. 178-206). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

de la Barre, S. (1994). Women as tourists in a post-colonial world: Insights for Defining Sustainable Tourism. 2nd Global Conference: Building a Sustainable World through Tourism, International Institute for Peace through Tourism. Montreal, Quebec, September 12-16.

de la Barre, S. (2005). Not Ecotourism?: Wilderness Tourism in Canada’s Yukon Territory. Journal of Ecotourism, 4(2) 92-107. DOI:10.1080/14724040409480342

de la Barre, S. (2009). Place identity, guides, and sustainable tourism in Canada’s Yukon Territory [PhD thesis, University of Alberta, Canada]. ERA Online Repository. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.7939/R3VP6S

de la Barre, S. (2011). Masculinist Narratives, Exclusion and Privilege on Canada’s Northern Frontier. Places, People, Stories Conference. Linnaeus University, Kalmar, Sweden. September 28-30.

de la Barre, S. (2012a). Wilderness and Cultural Tour Guides, Place Identity, and Sustainable Tourism in Remote Areas. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 21(6), pp. 825-844. DOI: 10.1080/09669582.2012.737798

de la Barre, S. (2012b). Chapter 12: Travellin’ around on Yukon Time. In Fulagar, S., Markwell, K. and Wilson, E. (eds). Mobilities: Experiencing Slow Travel and Tourism (pp. 157-169). Bristol: Channel View Publication.

de la Barre, S. (2021). Chapter 4: Creative Yukon: Finding Data to tell the Cultural Economy Story. In Scherf, K. (Ed.) Creative Tourism and Sustainable Development in Smaller Communities: Place, Culture, and Local Representation (pp. 109-135). Calgary: University of Calgary Press. Open Access book: https://press.ucalgary.ca/books/9781773851884/

de la Barre, S. and Brouder, P. (2013). Consuming Stories: Placing Food in the Arctic Tourism Experience. Journal of Heritage Tourism. 8 (2-3), 213-223. DOI: 10.1080/1743873X.2013.767811

de la Barre, S. and Sandberg, L. (2013). Mining the Ore and Pining for Women: Feminizing Place and Attracting Women to the Swedish Periphery. 5th Nordic Geographers Meeting, June 11-14, Reykjavik, Iceland.

Fullagar, S. and Wilson, E. (2012). Critical Pedagogies: A Reflexive Approach to Knowledge Creation in Tourism and Hospitality Studies, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 19, 1-4. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/jht.2012.3

Grimwood, B.S.R., Stinsona, M.J., King, L. J. (2019). A decolonizing settler story. Annals of Tourism Research, (79), 1-11. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.102763

Grimwood, B., Yudina, O., Muldoon, M. and Qiu, J., (2015). Responsibility in tourism: A discursive analysis, Annals of Tourism Research (50) 22–38. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2014.10.006

Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2006). More than an “industry”: the forgotten power of tourism as a social force. Tourism Management, 27(6), 1192-1208, 10.1016/j.tourman.2005.05.020.

Higgins-Desbiolles, F., & Blanchard, L. (2010). Challenging peace through tourism: Placing tourism in the context of human rights, justice and peace. In O. Moufakkir, & I. Kelly (eds.). Tourism Progress and Peace (pp.35–47). Oxford: CABI.

Higgins-Desbiolles, F. & Whyte, K.P. (2013). No high hopes for hopeful tourism: A critical comment. Commentary. Annals of Tourism Research. 40, 428-433. DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2012.07.005.

Hilton, C.A. (2021). Indigenomics: Taking a Seat at the Economic Table. New Society Publishers.

Jaggar, A. & Bordo, S. (Eds). (1989). Gender/Body/Knowledge: Feminist Reconstructions of Being and Knowing. Rutgers University Press.

Massey, D. (2005). for space. Sage Publications.

Müller, D.K., Carson, D.A., de la Barre, S., Granås, B., Jóhannesson, G.T., Øyen, G., Rantala, O., Saarinen, J., Salmela, T., Tervo-Kankare, K., and Welling J. (2020). Arctic Tourism in Times of Change: Dimensions of Urban Tourism. TemaNord 2020:529. Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers Available from: https://pub.norden.org/temanord2020-529/

Nicholson, L. (Eds.) (1990). Feminism/Postmodernism. Routledge.

Pearce, P. (2005). Tourism Academics as Educators, Researchers and Change Leaders. The Journal of Tourism Studies, 16(2) 21-33.

Phillimore, J. & Goodson, L. (Eds.) (2004). Qualitative research in tourism: Ontologies, Epistemologies and Methodologies. London and New York: Routledge.

Ramazanoglu, C. (1989). Feminism and the Contradictions of Oppression. Routledge.

Rantala, O., de la Barre, S., Granås, B., Þór Jóhannesson, G., Müller, D.K., Saarinen, J., Tervo-Kankare, K., Maher, P.T., and Niskala, M. (2019). Arctic Tourism in Times of Change: Seasonality. Nordic Council of Ministers. TemaNord 2019:528. ISSN 0908-6692. Available from: https://www.norden.org/en/publication/arctic-tourism-times-change-seasonality-0

Torabian, P. and Mair, H. (2021). Insurgent citizens: mobility (in)justice and international travel, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, DOI: 10.1080/09669582.2021.1945069

Weedon, C. (1987). Feminist Practice & Poststructuralist Theory. Basil Blackwell.