54 Towards Just Tourism and Praxis with Empathy and Care

Tazim Jamal

This essay is being written on a beautiful summer day in Victoria, British Columbia (Canada). The province has just chalked up an unprecedent heat wave and numerous wildfires rage in the province, obliterating the community of Lytton, B.C. while neighbouring provinces experience the worse air quality due to the smoke (https://www.vice.com/en/article/wx57qx/inspiring-canadas-air-quality-is-some-of-the-worst-in-the-world). But in this popular destination (Figures 1a, 1b), tourists are venturing tentatively forth during the COVID-19 pandemic (vaccines are now available), braving the delta variant and lifting of mask mandate by the provincial health authorities on Canada Day (July 1). I stopped at a local whale watching tour company where Liam (a pseudonym) explained how the business operated on carbon neutral principles, contributed a portion of tourist revenues to sustainable development projects, and endeavoured to facilitate ecosystem health through regenerative tourism, rather than merely sustaining the environment via sustainable tourism. Liam is an undergraduate student, his vision is inspiring for good tourism futures and hopefully to you too.

Figure 1a. Only a few resident orcas survive in the local waterways as the Pacific salmon they depend on are decimated. But tourists can still view transient (visiting) orcas on their marine tour. Why is the flag on the Empress at half-mast in early July, 2021? Photo credit: Tazim Jamal. July 9, 2021.

Figure 1a. Only a few resident orcas survive in the local waterways as the Pacific salmon they depend on are decimated. But tourists can still view transient (visiting) orcas on their marine tour. Why is the flag on the Empress at half-mast in early July, 2021? Photo credit: Tazim Jamal. July 9, 2021.

Figure 1b. Touristy scene in mid-July at the inner harbor of Victoria, B.C. (Canada). It’s business as usual, the Canadian flag back at full mast as the red flowerbed in front of Victoria’s House of Parliament blazes “WELCOME.” Photo credit: Tazim Jamal. July 19, 2021.

Figure 1b. Touristy scene in mid-July at the inner harbor of Victoria, B.C. (Canada). It’s business as usual, the Canadian flag back at full mast as the red flowerbed in front of Victoria’s House of Parliament blazes “WELCOME.” Photo credit: Tazim Jamal. July 19, 2021.

I shared my recent blog on regenerative tourism and just futures with Liam (https://goodtourismblog.com/2021/06/towards-a-new-paradigm-for-regenerative-tourism-and-just-futures/; see also Dredge, 2021). What does regenerative tourism mean? To Liam it seemed to mean being locally focused, restoring and improving ecological systems and the things it in, leaving the place healthier and more resilient, better than it was before. You as future women academics recognize, too, that his vision entails relationality—seeing the place and things in it in relation with each other and with the world. The tourist is a key actor in this relationality. Yet, how many tourists enjoying local seafood here understand the plight of the Pacific salmon? Or where that tasty fish on their plate came from? Was it certified as sustainably caught? Indeed, environmental literacy is and ought to be a key priority in marine and other eco-tours.

But is it just environmental literacy or would you agree that social literacy is crucial too? Should the visitor’s leisure hours also be troubled by learning about how tourism neocolonialism intersects with settler colonialism in this pretty destination? And about social injustices on tribal communities dispossessed of their lands and whose children are gradually being discovered in mass, unmarked graves beneath once active reservation schools in B.C? Will you see the relationality and potential of touristic spaces to foster a form of restorative justice and healing through dialogue and conative empathy—not just feeling empathetic, but acting on it to enable democratic action and change? (Jamal, Kircher and Donaldson, 2021)? Far too little has been done on the potential of touristic sites to facilitate dialogic healing and reconciliation with past injustices. It is a hope we pass on to you to embrace and actualize.

Liam’s intense thoughts were accompanied by that pandemic refrain, “smile with your eyes.” He had his mask on, the crusty fisherman I met on the wharf a few minutes later did not (he was outdoors, not engaging with the public as Liam was and the mask mandate was no longer in effect anyways). His weather-beaten face extended a sincere welcome as he chatted and offered to share with me the devilled eggs that he had just bought at the nearby fresh fish store, Finest at Sea (a sustainable treat awaits there—even the cutlery is biodegradable cellulose!). He was readying his boat for a long commercial tuna fishing trip. Liam and the tuna fisherman reminded me of many acts of kindness and generosity, and countless enriching conversations with local residents during my research and leisure travels. Yet, how well do we understand hospitality and visitor experience, after all those countless surveys and boxes of quantitative modelling (or the less than richly phenomenological experience studies which taken immense time and need generous word space in journals we publish in?)?

What does hospitality mean on unceded lands and the troubled history of Indigenous dispossession, or the exploitation of Indigenous and other ethnic and cultural minorities by dominant interests? What ought tourists to understand about the postcolonial history that the Empress Hotel’s high tea offerings is set in, the settler colonialism and unceded lands they are walking on (do look it up if you don’t know what this means)? How to communicate this in a way that facilitates equal dignity and equal respect (Nussbaum, 2011; see also Jamal, 2019, p. 68), critical awareness, solidarity, and healing of past wounds and injustices?

Rest assured, some enterprising research and poststructural insights on hospitality are arising to offer you a glimpse out of the modernist tropes that much of our literature is ensconced in (see, for example, Lynch 2017). Reach into inter-/trans-/post-disciplinary spaces for rich insights and directions, not just for your research publications but also for praxis. You may need to stand up for academic freedom, though—critical race theory is under attack in some US educational institutions currently (https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2021/07/22/critical-race-theory-founders/). What’s next?

More will be needed from you to facilitate the potential of just and fair tourism in a (post)pandemic Anthropocene. Black Lives Matter. Other lives, human and non-human, matter.

Rising to the challenge: Critical action with empathy and care

How are our students and future tourism academics researchers preparing for a future in the accelerating Anthropocene? Extreme weather, wildfires and climate change are all in the news. It’s a brave new world and I fear we are not preparing you well. You cannot seek shelter within academic ivory towers as ethical responsibility calls. How many delta variants and other global epidemics and pandemics await? Why did we not learn better from SARS? Droughts and water shortage, rising sea levels and extreme weather affect millions of inhabitants in the sub-tropics and other places worldwide. How long has it taken tourism scholars to wake up to the urgency of climate change? What will you do? Yours is a (post)pandemic world that requires critical action and change, i.e., praxis.

Neoliberal organizations like the UNWTO have been very slow to react to the pandemic, as have many governments and institutions that had the capacity to prioritize public health and swift action (Jamal and Budke, 2020). Cruise ships floated around the Pacific while Wuhan shut down on the eve of Chinese New Year. Neoliberal malaise. New ways of thinking and new approaches to tourism pedagogy, research and action are needed to facilitate collaborative engagement, critical thinking, and empowering students, residents and communities to act on global threats and exploitation of the local and global commons (ecological and social-cultural).

For example, you might incorporate community service-learning research into a critical pedagogy oriented to praxis, accompanied by an ethic of care and conative empathy (see open access paper by Jamal, Kircher and Donaldson, 2021). Your responsibility includes the public good, empowering students and empowering destination communities to achieve their aspirations for well-being and sustainability. But first reach out to understand the world of the other from the viewpoint of the other, i.e., exercise conative empathy to empower critical action and change. It is integral for facilitating constructive democratic action for justice and fairness, and coordination and regulation of an international tourism industry that continues to perpetuate deep structural injustices while it runs on smoothly oiled neoliberal values that benefit a select few. Merely reading or writing about it with epistemic empathy or affective empathy simply will not suffice (Jamal, Kircher and Donaldson, 2021).

Tackling structural injustices

It becomes quickly evident that many injustices are historically and institutionally entrenched. Taking a relational approach shows how the inanimate and the animate, the tangible and the intangible, the past, present and future, are deeply interwoven (e.g., Smith, 2021; see also Ch. 1 in Justice and Ethics in Tourism, Jamal, 2019). Issues like climate change and global plastic pollution are “wicked problems” embedded in economic as well as social and governance structures (education, justice, policing, etc.). So are historically entrenched racism and discrimination, such as ensue from imperialism and (settler) colonialism. The consequences are rarely fair or equitable; low income, poor and vulnerable groups are often the most adversely affected. But how well are structural injustices identified and addressed in tourism studies?

Political philosopher Iris Marion Young elaborates clearly on social justice and responsibility for structural injustices (see Young, 2003 example of sweatshops), Will you be brave enough to fill this gap in tourism studies that women academics ahead of you are beginning to fill in (e.g., Dillette, 2021)? Responsibility in a local-global tourism system to such structurally engrained global threats and injustices is necessarily global and local. See, for example, this open access article by Krisztina Elefheriou-Hocsak (https://goodtourismblog.com/2021/08/one-tourism-beach-at-a-time-local-action-can-help-turn-the-tide-on-marine-plastic/) on the response of a local Cyprus based NGO to marine plastic debris and plastic pollution in the Mediterranean destination.

However. it takes two to tango, and well-informed tourists (who are residents somewhere) can hold their policy makers accountable and ensure businesses exercise corporate social responsibility with the help of relevant policy. That, too, is among the tasks that await you in the challenging futures. Change is slow, time is racing, but there’s hope when friends joyously bring home these souvenirs for me —a hand-carved street etching and a cloth laundry bag from Four Points by Sheraton. “Look, no plastic” they say proudly, but they also recounted how much plastic had floated up on high tide in their old coastal home, now wall-to-wall with tourist hotels.

4 Points by Sheraton

Bring no plastic bags into Kenya

said Lufthansa before landing

So expect cloth laundry bags

At Nairobi’s Four Points by Sheraton

Nairobi National Park

Teemed with wildlife

But in neighboring Tanzania

plastic floated in with the tide

Maasai souvenirs delight visitors

Fragrant mandazi* fill their bellies

But to those who once lived there

Neither country said ‘welcome home’

April 13, 2019

Tazim Jamal, Bryan, Texas

*mandazi is a traditional sweet, fried bread consumed on the East African coast.

My hope is that you will not shy away from that necessarily critical but empathetic research ‘gaze’ to tackle global threats and structural injustices in the vast machinery of neoliberal globalization and international tourism. Will you be willing to let go of the modernist principles and Eurocentric ‘gurus’ that many of us ahead of you were trained to emulate? Developing a critical edge is part of a lifelong process of becoming and there are scars to be bear when you have the courage to tackle injustices in the local-global tourism system. Hope arises as you observe diverse researchers share their locally situated, standpoint epistemologies (Haraway (1988) and pluralistic worldviews (see, for example, Santafe-Troncoso and Loring, 2021; Escobar, 2017). As they illustrate, it is really important to understand the destination, its people, its history and its social-ecological context, before framing your research questions. Take the time to know the place well, let its beauties and its trouble speak to you. Understand how it speaks to visitors. Whose interests and aspirations are you working towards?

And so the journey continues, mine and yours, for we are always in the process of becoming (academic and “other”). You will find your way, have courage, take strength from this marvellous, enriching, enigmatic phenomenon called “tourism” for it has much to offer for enriching, transformative experiences, well-being, and restorative justice. For me it is an ongoing “battle” to shed old modernist entrapments and develop non-dualist, posthumanist sensibilities towards “good tourism” with inclusivity and care for human and non-human others (Guia and Jamal, 2020; see also https://atig.americananthro.org/sustainable-tourism/).

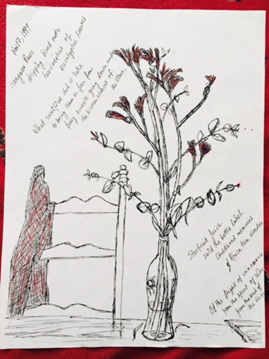

This little story below emerged late one night, unable to sleep, troubled by fiery red “kangaroo paws.” Yes, it is the name of the Aussie blooms a young woman had brought me. The empty juice bottle she left behind too…yet another item to recycle along with the memories it evoked. It was less than two years since I had graduated and arrived in Texas as a newly minted academic when I sketched the restless thoughts below. What will your story be to future women academics that you mentor? How will you advise them on the challenge of being a diverse scholar and a minority, bearing the indifference of a dominant group (see Young, 2011, on recognition of difference)? Like you, perhaps, some will have journeyed far from home in search of safety, security, and just tourism futures in research and praxis. Like my students, whom I sincerely thank, they will bring situated knowledges and pluralistic worldviews from the Global North and Global South to enrichen tourism studies.

Kangaroo Paws

dripping blood onto two varieties of eucalyptus leaves

What sacrifices did it take

to bring them so far from

fiery sunsets going down under

the broken silence of the Other.

Starfruit juice

said the bottle label

Childhood memories

of Africa torn asunder

Of the flight of innocence

from the spirit of Woman

from the soul of the Earth.

Sketch and poem by Tazim

November 17, 1999

Bryan, TX

Restless night. I went to bed a couple of hours before the Aggie Bonfire collapsed early on Nov. 18, 1999.

Written by Tazim Jamal, Texas A&M University, United States

References

Dillette, A. (2021). Roots tourism: a second wave of Double Consciousness for African Americans, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29 (2-3), 412-427. DOI: 10.1080/09669582.2020.1727913

Dredge, D. (2021, May 25). Regenerative tourism rising… and why it can’t be unseen. Medium. https://medium.com/the-tourism-colab

Escobar, A. (2017). Designs for the Pluriverse. Durham, NC: Duke University Press

Guia, J. and Jamal, T. 2020. A (Deleuzian) posthumanist paradigm for tourism research. Annals of Tourism Research, 84, 102982, Research Note. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102982.

Haraway, D. (1988). Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. Feminist Studies, 14 (3): 575-599.

Jamal, T. and Budke, C. (2020). Tourism in a world with pandemics: Local-global responsibility and action. Viewpoint, Journal of Tourism Futures. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-02-2020-0014.

Jamal, T. (2019). Justice and Ethics in Tourism. Routledge.

Jamal, T., Kircher, J. and Donaldson, J. P. (2021). Re-visiting design thinking for learning and practice: Critical pedagogy, conative empathy. Sustainability, 13(2): 964. Special issue on “Tourism: A Fecund Frontier for Cross and Multidisciplinary Enquiries in Sustainability.” Guest editors: J.M Cheer, S. Graci, C. Dolezal. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020964. Open access.

Lynch, P. (2017). Mundane welcome: Hospitality as life politics, Annals of Tourism Research, 64, 174–184.

Nussbaum, M. (2011). Creating capabilities: The human development approach. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Santafe-Troncoso, V., & Loring, P. A. (2021). Indigenous food sovereignty and tourism: the Chakra Route in the Amazon region of Ecuador. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(2-3), 392-41

Young, I. M. (2003). Political responsibility and structural injustice. Lindley Lectures; 41. University of Kansas, Department of Philosophy. Retrieved from https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/handle/1808/12416.

Young, I. M. (2011). Justice and the politics of difference. Princeton University Press.