96 Towards Welcome: Foregrounding Voices and Giving Visibility to the Marginalised in Tourism Workplaces and Beyond

Agnieszka Rydzik

Tourism and Society

My research stems from and is rooted in my worldview and my biography as a migrant woman. From a young age – having been born in late Communist-era Poland, brought up in the post-Communist pre-EU accession period of Poland’s history and then lived my adult life abroad as a citizen of the EU – I have been interested in understanding the workings of society and making sense of the othering processes that minority groups undergo, and how these may relate to social inequalities and (im)mobilities in broader society.

I see tourism as intrinsically connected to everyday social realities and tied up in the complexities of the social world of today. Tourism provides ‘a window through which the real social world of the everyday lives of ordinary members of society can be glimpsed’ (McCabe, 2002, p.72). This also means that tourism can reflect existing societal divisions, reinforce social inequalities and immobilities. This sociological view of tourism has been the focus of my research.

My research is situated at sociological, disciplinary and methodological crossroads, and broadly inscribed within the critical tourism approach that situates tourism within wider socio-political and cultural contexts (Wilson, Harris and Small, 2008), advocates commitment to ‘tourism enquiry which is pro-social justice and equality and anti-oppression’ (Ateljevic, Morgan and Prichard, 2007, p. 3) and ultimately strives to create a better society. I have always strongly believed that tourism research needs to constantly push the boundaries in terms of topics and perspectives as well as who is being researched and who does the research.

The focus of my work is not on tourists and their experiences per se but on 1) mobilities in a broader sense, including of those who are mobile in some ways yet often immobilised, excluded or disadvantaged in other ways, such as migrants (Rydzik et al, 2012; Rydzik, 2017b); 2) and also those who provide for tourists i.e. workers and their realities, in particular precarious workers and marginalised groups who often lack power to challenge inequalities (Rydzik and Anitha, 2020; Rydzik and Kissoon, 2021); as well as 3) tourism discourses and representations that often shape who is included and/or excluded (Rydzik, Agapito and Lenton, 2021).

In writing this piece, I had an opportunity to step back and reflect on the interconnections and linkages between my research projects and contributions; how they speak to each other and the golden thread that conceptually connects them. This piece is a result of these reflections.

Through my research, in one way or another, I have sought to understand how various minority groups – the perceived or constructed Others (e.g. migrant workers, young adult workers, women in male-dominated occupations) – are represented and how they deploy agency through the tools available to them to challenge inequalities in unfamiliar and, in some respects, hostile environments. I use the term ‘Other’ in a broad sense as the cultural and social Other that is perceived as threatening established norms and the social order, and unsettling perceived fixed boundaries (Bauman, 1991, 1997):

“Everyday engagement with the ‘other’ is fraught with difficulties; sometimes the ‘other’ is devalued or in extreme cases rejected. In the case of hospitality, the ‘other’ is often forced to take on the perceptions of the ‘host’” (O’Gorman, 2006, p. 55).

At the core, my research is about lived experiences of (un)welcome for marginalised groups in workplaces and local communities: how they navigate these; how they are changed by these and how they deploy these experiences to transform environments they function within. I am interested in the everyday experiences of welcome, often mediated through interactions between the perceived Other and those with more power (i.e. majority groups), the power relations underpinning these encounters, and how these are communicated and negotiated.

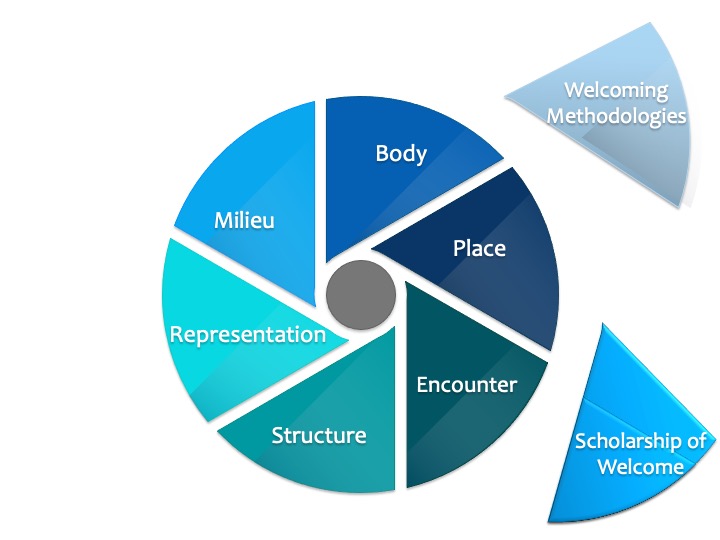

Framework for conceptualising experiences of (un)welcome

The framework (see Figure 1.) I set out here brings together the multiple interlinking dimensions of (un)welcome. The framework can be used in a range of different contexts to problematise and understand perceptions and experiences of welcome from the perspective of the constructed Other. This could be, for example, tourists, minority groups, communities, workers. With migrant women tourism workers occupying the lower rungs of the employment ladder, one could explore their experiences of (un)welcome through examining their embodied experiences at work (body), the gendered nature of their workplace environments (place), how power relations are exercised at work in relation to their nationality, gender and role (encounter), how organisational norms position them (structure), how discourses frame how others may see or pre-judge them (representation), and broader socio-political transformations that may ‘other’ them – such as Brexit – or welcome them, such as gender inclusivity initiatives (milieu). It is through interrogating the intersections of these six dimensions that we can grasp the lived experience of welcome for those who are the focus of our research. This piece ends by discussing welcoming methodologies that can foreground participants’ voices and give visibility to their experiences, and the need for a greater focus on a scholarship of welcome that engages students with social justice education to shape more reflective and critical citizens as well as professionals.

Body

Welcome is an embodied and affective experience. It is felt in and through the body. For minority groups, (un)welcome can manifest in how their presence (accents, physical appearance, body-age) is received by the majority group. It can also manifest in how their bodies respond to certain situations (e.g. through anxiety, stress) and can impact on work satisfaction, relationships, perception of self, confidence and aspirations. Visible markers of identity in particular, such as gender, race/ethnicity, age and disability, can contribute to feelings of exposure and unwelcome.

From the perspective of tourists, various scholars have examined gendered, embodied and racialised experiences of travellers (e.g. Dillette, Benjamin and Carpenter, 2018; Sedgley et al., 2017; Small, 2021, 2017; Wilson and Little, 2008) and how they are constrained but also how they develop strategies to cope with non-welcome and exclusion. The focus of my research has been on workers and their experiences. Workers’ bodies, in particular those in customer service roles, are often subject of gaze (from customers, co-workers, employers) and workers can feel the need to dim aspects of their identity to blend in and conform to the norms of the workplace. While this can help them feel accepted, it can also come with an emotional cost and curtail their potential.

For example, young adults on zero-hour contracts in hospitality felt undervalued and invisible in their workplaces (Rydzik, 2019, see also Mooney, 2016). The work I am currently developing on this shows how young adults’ experiences of socialisation into the world of work through hospitality jobs are often underpinned by experiences of unwelcome and exclusion. Their young bodies attracted unwanted attention and incidents of sexual harassment were part of their everyday experience at work. For migrant women working in customer-facing roles in tourism, their gender, age, ethnicity, physical appearance and accent impacted on how they were perceived and treated, e.g. their accents made their otherness salient and evoked stereotypical assumptions (Rydzik et al., 2017). Feelings of exclusion and not fitting in can accompany some workers throughout their working lives, with constant attention being given to presentation of self.

Place

Welcome is situated in a physical space that is subjectively experienced, fluid and constantly evolving, and can be both othering and embracing. Workers, local communities, tourists, employers, DMOs, policymakers and stakeholders all engage in place-making. In essence, they have an impact on shaping experiences of welcome.

In our study, migrant residents often experienced racism and prejudice in the Lincolnshire town of Boston (UK) but also found spaces of conviviality (e.g. in allotments or through participating in family events) (Annibal et al., 2020). Despite challenges, many developed feelings of attachment to Boston (e.g. through children in local schools) and actively transformed where they lived by embedding into and shaping communities (e.g. through church activities, Polish/Lithuanian Saturday schools and ethnic minority businesses) and engaging with local heritage. Living in Boston was thus both marked by fluid, contradictory and subjective experiences of welcome and non-welcome.

Workplace environments and the way workplaces are designed can become spaces of inclusion or exclusion. For example, findings from another study (Rydzik and Ellis-Vowles, 2019) show how women in male-dominated environments, namely microbreweries, engage in placemaking and identity work to challenge workplace exclusion, overcome constraints, gain acceptance and differentiate themselves. In traditionally male-dominated brewery environments, where physical strength is considered key, women brewers’ bodies were considered out of place and constructed in opposition to male brewers. Women asserted their right to belong by navigating their physical working environments in specific impactful ways. For example, through ‘demonstrating physical competence, adapting their physical workspaces, and developing bodily techniques to use tools and machinery primarily designed for male bodies’ (Rydzik and Ellis-Vowles, 2019, p. 495). They also discursively framed their working bodies ‘as strong, fit and able’, while acknowledging ‘limitations of their bodies’ and developing ‘everyday tactics to practically work around these’ (Rydzik and Ellis-Vowles, 2019, p. 495).

Encounter

Welcome is experienced and perceived through interactions often imbued in asymmetrical power relations between hosts and guests, locals and foreigners, workers and employers.

In my study, young workers in hospitality experienced insecuritisation due to uneven power relations between them and customers, co-workers and managers, where young adults’ agentic power was often undermined, vulnerability amplified, and insecurity normalised (Rydzik, 2019). Due to power asymmetries, they had limited agency to negotiate advantageous working arrangements. While hospitality work enabled young workers in particular ways and provided opportunities, power asymmetry in employment relations reinforced perceptions of insecurity and aggravated inequalities, with limited options to redress. This not only impacted on relations and self-perception but also conditioned them into precarious employment and normalised prospects of an insecure future.

Migrant women tourism workers also had to find ways to exercise agency through oppressive employment relations. Analysis of their responses to exploitation showed that migrant women tourism workers engaged in practices of resilience, reworking and resistance (Rydzik and Anitha, 2020). They ‘saw themselves as active agents with long-term goals rather than passive powerless victims of exploitation’ and navigated hyperexploitative work relations through devising coping tactics ‘in response to difficulties encountered at work, which helped them cope with ill-treatment from co-workers, managers and customers’ (Rydzik and Anitha, 2020, p. 889). Workplace encounters are thus key in mediating subjective experiences of (un)welcome for minority groups as one’s positionality in these encounters is constantly negotiated and renegotiated.

Structure

Welcome is often mediated by hard-to-fathom structures and norms that have to be understood and navigated. Newly arrived migrant workers or young adults new-to-the-workplace can find this particularly difficult, opening them to exploitative working conditions.

Migrant women in tourism workplaces experienced structural limitations that affected their career prospects. While tourism work enabled their spatial mobility and supported some of their aspirations, on the whole, many experienced limits to vertical occupational mobility and felt constrained through limited promotion opportunities and having their occupational mobility limited to gendered roles, resulting in them developing strong intentions to leave the industry (Rydzik et al., 2012).

Similarly, the precarious nature of hospitality jobs resulted in young workers experiencing limited control over working times and limited development prospects, while women brewers had to challenge gendered roles in microbreweries both on collective and individual levels to gain acceptance and recognition, and challenge stereotypical assumptions around suitability. This was also true for migrant women entrepreneurs who challenged nationality-based stereotypes at work and in the community, and negotiated gendered assumptions at home and beyond to achieve their entrepreneurial and mobility goals within societal structures that can make it tricky for them to succeed on their terms (Zeinali et al., 2021).

Representation

Welcome is affected by wider discourses and the politics of representation. While experiences of welcome are subjective, media and tourism promotional materials are inscribed in constructing narratives that privilege some groups and exclude others. This often reinforces the dominant stereotyped imagery in society and has the power to shape perceptions. How minority groups are portrayed in the mainstream media, by DMOs or in tourism promotional materials can be powerful in projecting welcome or non-welcome, and be either inclusive or othering.

In our paper (Rydzik, Agapito and Lenton, 2021), trying to unpack this, we examined dominant representations of couples and places in wedding tourism promotional materials over 16 years. Our analysis showed that majority-centric imagery remained dominant, with minority groups consistently significantly under-represented and marginalised, despite wider societal changes. In the paper, we proposed an eleven-category visibility framework that allows for an examination of omissions, inequalities and power asymmetries, making these more visible. We also called on the ‘industry to critically reflect on and move away from stereotyped, gendered and heteronormative images and instead capture the complex, multi-layered and diverse dimensions of the society of today and tomorrow’ (Rydzik et al., 2021, p. 11).

This dimension of the framework complements the other dimensions by acknowledging that attitudes and perceptions are often influenced by the media and constructed through othering narratives that can directly affect experiences of minority groups.

Milieu

Welcome is influenced by the socio-political and cultural milieu. The social context and political environment of the time impact on attitudes, mobilities, behaviours and feelings of exclusion and inclusion.

The 2004 accession of the eight Central and Eastern European (CEE) nations to the EU enabled mass mobility of citizens from these nations to other EU countries in search of opportunities (Rydzik, 2017b), including entrepreneurial opportunities (Zeinali et al., 2021), and gave them equal rights and access to EU labour markets, with UK tourism workplaces quickly becoming reliant on CEE migrants, in particular migrant women (Rydzik et al., 2017).

In the UK, this transnational mobility was halted by Brexit which directly affected the status and rights of EU citizens in the UK, limiting their access to jobs but also leading to increased feelings of anxiety and unwelcome. In our study, migrants in Boston, a borough in Lincolnshire that had the highest proportion of the Leave vote in the 2016 referendum, strongly felt societal changes in attitudes post-referendum. This led them to re-evaluate their previously set plans and increased their feelings of uncertainty about the future, undermining their sense of rootedness and belonging in the host country and altering their trajectories (Annibal et al., 2020).

More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated implementation of technological solutions in tourism. In our paper, we argue that while increasing health and safety, from the worker perspective, this can also result in increased digital control of workers and introduce intelligent automation solutions that could negatively affect disadvantaged workers the most (Rydzik and Kissoon, 2021). This can alienate workers and diminish worker voice. How this will play out in terms of exacerbating or reducing inequalities between dominant and out-groups remains unknown but is key to consider before the impacts take hold.

Welcoming methodologies

If we are to examine social inequalities and embrace social justice research in tourism, it is key to reflect on the methodologies we use to achieve this. I have found participatory methodologies, namely arts-based participatory approaches, particularly powerful (Rydzik et al., 2013). For my study, migrant women tourism workers created visual representations of their experiences of living in the UK and their working lives. These ranged from photographs, paintings, visual essays to poetry. I organised a dissemination event where these visual creations were exhibited during a community event, with over 200 visitors in two days, with the aim of giving voice and visibility to this often marginalised and stereotyped group and their lived experiences.

There are numerous benefits of adopting visual participatory approaches. Firstly, they can facilitate researcher and participant reflexivity, resulting in a more meaningful collaboration and redressing power relations between the researcher and participants (Rydzik et al., 2013, p. 286). Secondly, visual participatory methodologies can allow access to deeper layers of experience and provide richer insights into participants’ lives. Thirdly, participants and their experiences are given more visibility, allowing for active engagement in the research process, knowledge co-creation and self-representation. Participatory approaches are particularly suitable when exploring issues of social justice and underprivileged groups as they can ‘promote change, empowerment and transformation’ (p. 301).

Scholarship of welcome

I see pedagogic practice as an intrinsic part of my scholarly work. I believe that engaging students in conversations about social justice is key in preparing them to become critical and reflective tourism practitioners. Social justice education provides ‘tools for examining how oppression operates in both the social system and in the personal lives of individuals from diverse communities’ (Bell, 2016, p. 4). Developing student use of these tools to help them examine inequalities in the industry and in wider society is not easy and sometimes requires students and educators to engage in uncomfortable yet honest conversations and face truths about tourism and society that are often not talked about. Yet, this is key if the goal is to interrupt oppressive practice and create a better and more welcoming future for all.

I have embedded the principles of social justice education in my teaching in a number of ways. I have engaged students in live research projects (Rydzik, 2015) and reflective practice (Rydzik, 2017a). I also embed social justice content – covering inequalities in tourism promotional materials, gendered and racialised experiences of travellers and workers, exclusion in tourism, critical issues in tourism workplaces – in my classes and use assessments where students explore timely societal issues in tourism from the perspectives of under-privileged groups. A showcase of student work can be accessed publicly online (Tourism Students Virtual Conference, 2021). Embedding a critical tourism approach in the tourism, events and hospitality curricula can help us contribute to creating a more just and sustainable world of tomorrow (Pritchard, Morgan & Ateljevic, 2011).

Towards Welcome

Welcome is ‘a form of social oil and is at the heart of making societies function in a healthy and effective fashion’ (Lynch, 2017, p. 182). While receiving welcome can provide ‘affirmation of the self’, non-welcome can affect one’s sense of identity (Lynch, 2017, p. 182). It is thus vital to consider how (un)welcome manifests in the lived experience of minority groups, and I have strived to explore this in my work. It is through gaining this understanding that we can come closer to making tourism experiences, workplaces and communities more inclusive.

Written by Agnieszka Rydzik, University of Lincoln, UK

Read Agnieszka’s letter to future generations of tourism researchers

References

Annibal. I., Price, L., Rydzik. A. & Sellick, J. (2020). Inclusive Boston. Project Report for Boston Borough Council and Partners.

Ateljevic, I., Morgan, N. & Pritchard, A. (2007). Editors’ Introduction: Promoting an Academy of Hope in Tourism Enquiry. In I. Ateljevic, A. Pritchard & N. Morgan (Eds.), The Critical Turn in Tourism Studies: Innovative Research Methods (pp. 1-8). Oxford: Elsevier.

Bauman, Z. (1991). Modernity and Ambivalence. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bauman, Z. (1997). Postmodernity and its Discontents. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bell, L. A. (2016). Theoretical Foundations for Social Justice Education. In M. Adams and L.A . Bell, and P. Griffin (Eds.), Teaching for Diversity and Social Justice (pp.3-26). New York: Routledge.

Dillette, A. K., Benjamin, S. and Carpenter, C. (2018). Tweeting the Black Travel Experience: Social Media Counternarrative Stories as Innovative Insight on #TravelingWhileBlack. Journal of Travel Research, 58(8), 1357-1372 https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287518802087

Lynch, P. (2017). Mundane Welcome: Hospitality as life politics. Annals of Tourism Research, 64, 174-184 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.04.001

McCabe, S. (2002). The Tourist Experience and Everyday Life. In G. Dann (Ed.), The Tourist as a Metaphor of the Social World (pp. 61-77). Wallingford: CABI.

Mooney, S. (2016). Wasted youth in the hospitality industry: Older workers’ perceptions and misperceptions about younger workers. Hospitality & Society, 6(1), 9-30. https://doi.org/10.1386/hosp.6.1.9_1

O’Gorman, K. (2006). Jacques Derrida’s philosophy of hospitality. The Hospitality Review, 8(4), 50-57.

Pritchard, A., Morgan, N. & Ateljevic, I. (2011). Hopeful tourism: A new transformative Perspective. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(3), 941-63.

Rydzik, A. (2015). Developing critical and reflective tourism practitioners through a research-based learning project. Project Report. University of Lincoln.

Rydzik, A. (2017a). Creating and sharing stories of work: from individual experience to collective reflection. Euro-TEFI Conference, 20- 22 August 2017, Aalborg University, Denmark.

Rydzik, A. (2017b). Travelers, tourists, migrants or workers? Transformative journeys of migrant women. In C. Khoo-Lattimore & E. Wilson (Eds.) Women and Travel: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives. Oakville: Apple Academic Press.

Rydzik, A. (2019). How tourism jobs socialise young workers into neoliberal understandings of work and themselves as workers. Critical Tourism Studies Conference, 24-28th June 2019, Spain.

Rydzik, A. & Anitha, S. (2020). Conceptualising the agency of migrant women workers: Resilience, reworking and resistance. Work, Employment and Society, 34(5), 883-899. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0950017019881939

Rydzik, A. & Ellis, V. (2019). ‘Don’t use the “weak” word’: Women brewers, identities and gendered territories of embodied work. Work, Employment and Society, 33(3), 483–499. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0950017018789553

Rydzik, A. & Kissoon, C.S. (2021). Decent work and tourism workers in the age of intelligent automation and digital surveillance, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1928680

Rydzik, A., Agapito, D. & Lenton, C. (2021). Visibility, Power and Exclusion: The (Un)Shifting Constructions of Normativity in Wedding Tourism Brochures. Annals of Tourism Research, 86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.103090

Rydzik, A., Pritchard, A., Morgan, N. & D. Sedgley (2012). Mobility, migration and hospitality employment: Voices of Central and Eastern European Women. Hospitality & Society, 2(2), 137-157. https://doi.org/10.1386/hosp.2.2.137_1

Rydzik, A., Pritchard, A., Morgan, N. & D. Sedgley (2013). The Potential of Arts-based Transformative Research. Annals of Tourism Research, 40(1), 283-305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2012.09.006

Rydzik, A., Pritchard, A., Morgan, N. & D. Sedgley (2017). Humanising Migrant Women’s Work. Annals of Tourism Research, 64, 13-23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.02.002

Sedgley, D., Pritchard, A., Morgan, N. & Hanna, P. (2017). Tourism and autism: Journeys of mixed emotions. Annals of Tourism Research, 66, 14-25, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.05.009

Small, J. (2017). Women’s “beach body” in Australian women’s magazines. Annals of Tourism Research, 63, 23-33, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.12.006

Small, J. (2021). The sustainability of gender norms: women over 30 and their physical appearance on holiday, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1874396

Tourism Students Virtual Conference (2021). Tourism Students Virtual Conference. Retrieved from http://www.travel-conference.co.uk

Wilson, E. & Little, D. E. (2008). The Solo Female Travel Experience: Exploring the ‘Geography of Women’s Fear’. Current Issues in Tourism, 11(2), 167-186. https://doi.org/10.2167/cit342.0

Wilson, E., Harris, C., & Small, J. (2008). Furthering critical approaches in tourism and hospitality studies: Perspectives from Australia and New Zealand. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 15, 15-18. https://doi.org/10.1375/jhtm.15.15

Zeinali, M., Rydzik, A. & Bosworth, G. (2021). Women’s post-migration narratives of entrepreneurial becoming. In D. Hack-Polay, A. B. Mahmoud, A. Rydzik, M. Rahman, P. Igwe & G. Bosworth (Eds.) Migration as creative practice: An interdisciplinary exploration of migration (pp. 101-119). Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited.