58 Understanding Tourist Behavior in a Changing Environment

Astrid Kemperman

The travel and tourism industry is among the most affected sectors by the Covid-19 pandemic, with a massive fall in international tourism demand. While the industry is currently recovering, the World Tourism Organization argues that this fall in demand offers the opportunity to rethink the tourism sector and build back better towards a more sustainable, inclusive, and resilient sector that ensures that the benefits of tourism are enjoyed widely and fairly (UNWTO, 2021). Over the last decades, it has become clear that the growth of tourism brings significant challenges with it and is itself also influenced by for example climate change, pollution, decreasing natural resources, growing populations, and local and cultural differences. The negative environmental impacts of tourism are substantial: tourism puts stress on local land use, can lead to increased pollution, and more pressure on endangered species and the natural habitat. A more sustainable tourism approach would mean taking into account the current and future economic, social and environmental impacts, the preferences and needs of visitors, the industry, the environment, and host communities (UNWTO, 2021).

At the same time, recent technological and digital innovations also change the way people live, work, travel, interact with one another, and how they spend their free time. The borders between the digital, social, and physical environment are more and more intertwined. Technological advances, information dissemination, the influence of social networks, and increasing available free time and monetary budgets have further strengthened the need to create sustainable development opportunities for the tourism industry to support and improve efficient destination planning, management, and local community empowerment and inclusiveness. Moreover, as argued by Gretzel and Koo (2021), these technological developments lead to a convergence of urban residential and touristic spaces, and there is value in merging so-called smart tourism and smart city planning and management development goals to serve both residents and tourists in the best possible ways.

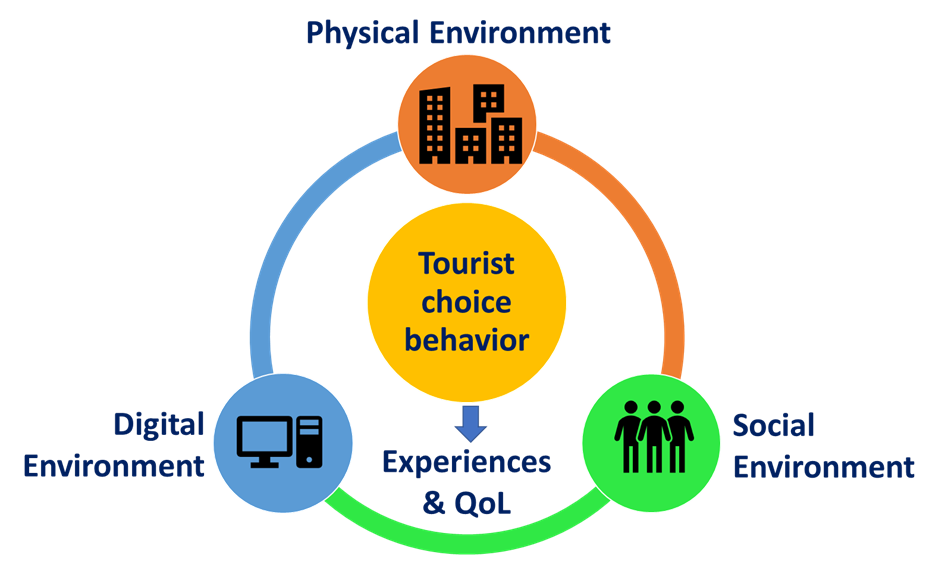

Research is needed to test the possible impact of new technology on tourists, their needs, preferences and activities, social relationships, and interaction with the environment. These considerations drive my general research aim: to develop a deeper understanding of individuals’ needs, preferences, and spatial activity patterns within the context of the digital, social, and physical environment to help find solutions for these challenging problems. In this chapter, a concise overview of my research, from the past to present and some new ideas are presented and discussed, as shown in figure 1: investigating tourist choice behavior within a changing digital, social and physical environment to support planning and design of environments that enhance tourist experiences and quality of life.

Facets of tourist choice behavior

Central in my research over the years is understanding and adding to knowledge on tourist choice behavior, and I have been doing so taking a quantitative research approach using advanced data collection methods (e.g., dynamic stated choice experiments) and modeling approaches (e.g., discrete choice modeling, Bayesian Belief Network models). Tourists make a variety of choices including whether or not to travel, destination choice (e.g., Kemperman, Borgers & Timmermans, 2002b), transport mode choice (e.g., Grigolon, Kemperman & Timmermans, 2012c), accommodation choice (e.g., Randle, Kemperman & Dolnicar, 2019), trip duration choice (e.g., Kemperman, Borgers, Oppewal & Timmermans, 2003), and what activities to undertake while at a specific destination (e.g., Kemperman, Joh, & Timmermans, 2004). However, when explaining and predicting tourist choice behavior a variety of unique properties need to be taken into account. Over the years I have investigated some of these aspects.

First, compared to other types of choices like transport mode choice, tourists are inclined to show variety-seeking behavior in their choices over time, meaning that a time-invariant preference function is not reasonable (Kemperman, 2000). Variety seeking behavior in tourists may be influenced by a variety of factors such as availability of choice alternatives or changes in their characteristics, differences in decision-making contexts, different choice motivations, different travel party group composition or travel companions, and in general a basic desire for novelty (Kemperman, Borgers, Oppewal and Timmermans, 2000). Specifically, a discrete choice model of theme park behavior including seasonal and variety-seeking effects is proposed and estimated and the external validity of the model is assessed leading to accept the hypothesis that tourists differ in their preferences for theme parks by season and show variety-seeking behavior over time (Kemperman, Borgers & Timmermans, 2002b).

In general, tourist choices, certainly compared to for example commuter choices, are made less frequently, represent high-involvement decisions, often include multiple choice facets, the decision process may take longer, and they might be based on well-established long-term agendas (Grigolon, 2013). A portfolio choice experiment concerning the combined choice of destination type, transport mode, duration, accommodation, and travel party for vacations is developed (Grigolon, Kemperman & Timmermans, 2012b). Specifically, the influence of low-fare airlines on the portfolio of vacation travel decisions of students is investigated. The findings confirm earlier studies that conclude that travel-related decisions for tourists, in general, are multi-faceted and not only related to the destination itself (e.g., Dellaert, Ettema, & Lindh, 1998; Jeng & Fesenmaier, 1997; Woodside & MacDonald, 1994).

In another study, based on revealed data about vacation history in terms of the long holidays of a sample of students, interdependencies in the vacation portfolios and their covariates are explored using association rules (Grigolon, Kemperman & Timmermans, 2012a). The portfolios include joint combinations of destination, transport mode, accommodation type, duration of the trip, length of stay, travel party, and season. Results show and confirm dependencies between vacation portfolio choice facets and their covariates. These insights provide a better understanding of tourist choice behavior and the context in which choices are made and can support policy and planning decision-making.

Tourist activity choices

When tourists are at a destination or in a city there is the timing and sequencing of tourists’ activity choices. Over-usage and congestion of specific attractions or facilities are difficult to avoid and may cause severe problems for a destination or city. For destination planning and management, it is important to understand how tourists behave in time and space, how the demand for various activities and attractions fluctuate over time, and how they can be accommodated and directed.

One of my first studies on this topic (Kemperman, Borgers & Timmermans, 2002a) introduces a semi-parametric hazard-based duration model to predict the timing and sequence of theme park visitors’ activity choice behavior that is estimated based on observations of tourist activity choices in various hypothetical theme parks. The activities include a description of the activity/attraction as well as their waiting time, activity duration, and location. The main findings support the prediction of how the demand for various activities is changing during the day and how the visitors are distributed over the activities in the park during the day. This information is relevant for visitor use planning to optimize the theme park experience.

In another study on visitors’ activities undertaken while tourists are at a destination, we focus on interrelated choices of tourists, multi-dimensional activity patterns as opposed to particular isolated facets of such patterns (Kemperman, Joh, & Timmermans, 2004). Moreover, in this study, it is tested whether activity patterns of first-time visitors tend to differentiate from the activity patterns of repeat visitors, mediated by their use of information. Differences between the two groups are assumed to be reduced when first-time visitors use information about the available activities and the spatial layout of the theme park. Specifically, the sequence alignment method is applied to capture the sequence of conducted activities. We conclude that the activity patterns of the two groups do differ, first-time visitors follow a very strict route in the park as indicated by the theme park, while repeat visitors have a more diverse order in their activity pattern. However, the difference between the two groups is reduced when first-time visitors use information about the available activities and the spatial layout of the park.

In an aim to measure and predict tourists’ preferences for combinations of activities to participate in during a city trip, a personalized stated choice experiment is developed and binary mixed logit models are estimated on the choice data collected (Aksenov, Kemperman & Arentze, 2014). An advantage of this approach is that it allows estimation of covariances between city trip activities indicating whether they would act as complements or substitutes for a specific tourist in his/her city trip activity program. The model provides information on combinations of activities and themes that tourists prefer during their city trip and that can be used to further fine-tune the recommendations of city trip programs and optimize the tourist experience.

As shopping is one of the most important activities for tourists, we also investigate shopping route choice behavior in a downtown historic center, including the motivation for the shopping trip, familiarity with the destination, and whether the shopping route through the downtown area is planned or not before the visit (Kemperman, Borgers, & Timmermans, 2009). A model of tourist shopping behavior is proposed and estimated to investigate differences in route choice behavior of various types of tourist shoppers. The results indicate that shopping supply and accessibility, some physical characteristics, and the history of the route followed are important factors influencing route choice behavior. Furthermore, it can be concluded that shopping motivations, familiarity with the area, and planning of the route affect tourist route choice behavior. The model allows investigating the effects of environmental characteristics on route choice behavior and assessing various future planning scenarios, such as changes in physical aspects in the downtown area, or changes in the supply of shops to optimize visitors’ shopping trips.

Social and physical environment and tourist choice behavior

The social environment including the social relationships and cultural milieus within which tourists interact and make their choices is intertwined with the physical, natural, and built environment in which tourists travel and their activities take place.

First, a study in which we explore children’s choices to participate in recreational activities and the extent to which their choices are influenced by individual and household socio-demographics, and characteristics of the social and physical environment (Kemperman & Timmermans, 2011). Travel and activity diaries of a large sample of children aged 4-11 years old in the Netherlands are used to collect data on out-of-home recreational activity choices and this data is merged with measures describing the social and physical living environment. A Bayesian belief network modeling approach is used to simultaneously estimate and predict all direct and indirect relationships between the variables. Results indicate that recreational activity choices are, among others, directly related to the socio-economic status of the household, the perceived safety of the neighborhood, and the land use in the neighborhood. Planners and designers are recommended to find a good land use mix, and specifically, make sure that they focus their attention on safety issues to stimulate children’s recreational activity choices.

In a more recent study, we investigate with a stated choice experiment how different presentations of cause-related corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives affect holiday accommodation choices, with a specific focus on the relative importance of tourist involvement, the message-framing, and the donation proximity (Randle, Kemperman, & Dolnicar, 2019). In a tourism context, we see that an increasing number of organizations implement so-called social corporate responsibility (CSR) initiatives, meaning they give some of their benefits back to the local community, society and, or the environment and it is of interest to see whether tourists take these initiatives into account when making their choices and how messages are valued. We found that different market segments are affected differently by these SCR initiatives when choosing their holiday accommodation. Specifically, there is one CSR-sensitive segment that cares about nature and the natural landscape, experiencing nature intensely, and efforts to maintain unspoiled surroundings and scores higher on community involvement than other segments. In general, it is found that negative message framing is the most promising option in terms of positively influencing tourist choices. It is concluded that although CSR initiatives do not appear to have a consistently positive effect on all tourist accommodation choice behavior, neither do they negatively affect demand. Specifically, it is advised to tailor CSR messages such that they are most effective in influencing the SCR-sensitive tourist segment.

Tourism can have an enormous environmental impact, and specifically, air travel negatively contributes to global carbon emissions. A voluntary carbon offset program supports airlines to take proactive measures to reduce the environmental impact. We have tested, using a stated choice experiment, the effectiveness of different communication messages to increase voluntary purchasing of carbon offsets by air passengers (Ritchie, Kemperman, & Dolnicar, 2021). Results indicate that tourists who book their flights prefer carbon offset schemes that fund local programs over international ones, that are effective in mitigating emissions, and are accredited. The willingness to pay for carbon offsets when booking for a group is lower than when booking an individual flight for oneself. Moreover, the tourist market can be divided into different segments with their characteristics, including age, employment status, frequent flyer membership, and flight behavior. Therefore, it is important to target the segments for aviation carbon offsetting by matching certain types of attributes and present an optimal program to each of the segments.

Integration of the digital environment in tourist choice behavior

Nowadays digital technologies can support tourists in making their choices, planning their trips, and optimizing their experiences (e.g., Buhalis, 1998; Gretzel, Mitsche, Hwang & Fesenmaier, 2004; Kemperman, Arentze, & Aksenov, 2019; Rodriguez, Molina, Perez & Caballero, 2012; Steen Jacobsen & Munar, 2012). We introduce this concept of ‘smart routing’ in the development of a recommender system for tourists that takes into account the dynamics of their personal user profiles (Aksenov, Kemperman, & Arentze, 2016). This smart routing concept relies on three levels of support for the tourist: 1) programming the tour (selecting a set of relevant activities and points of interests to be included in the tour, 2) scheduling the tour (arranging the selected activities and point of interests into a sequence based on the cultural, recreational and situational value of each) and 3) determining the tour’s travel route (generating a set of trips between the activities and point of interests that the tourist needs to perform to complete the tour). This approach aims to enhance the experience of tourists by arranging the activities and points of interest together in a way that creates a storyline that the tourist will be interested to follow and by reflecting on the tourists’ dynamic preferences.

For the latter, an understanding of the influence of a tourist’s affective state and dynamic needs on the preferred activities is required (Arentze, Kemperman, & Aksenov, 2018). Finally, the activities and points of interest are connected by a chain of multimodal trips that the tourist can follow, also in relation to their preferences and dynamic needs. Therefore, each tour can be personalized in a ‘smart’ way optimizing the overall experience of the trip. In the study, the building blocks of this concept are discussed in detail and the data involved, and finally, a prototype of the recommender system is developed.

Conclusion and future research

This chapter gives an overview of research that I have worked on over the years in collaboration with other researchers to develop a deeper understanding of tourists’ choice behavior and to generate insights and provide support for policy, planning, and managerial decision making in finding answers to the challenges the tourism industry and environment are facing. Specifically, examples of research are presented that tested in different ways facets of tourists’ needs, preferences, and spatial activity patterns within the context of a changing digital, social and physical environment.

Based on this overview some avenues for future research, in line with the presented framework in Figure 1, can be given. First, the studies presented show how tourist choices are influenced by their social and physical environment and that in understanding these choices it is important to take these aspects into account. Specifically, the social environment or social influence by family members, peers, or colleagues might also be an important additional explanatory facet in explaining tourist choices, for example in understanding and promoting the choice for sustainable tourist behavior. Research has also indicated that role of social media, online reviews, and social influencers have become increasingly important in the choices tourists make, and including the influence of someone’s social network, colleagues, peers, and family members in predicting tourist choice behavior is an interesting research opportunity (Kemperman, 2021).

The digital and technological developments support and improve other ways of data collection, for example by using virtual reality, simulators, or eye-tracking (e.g., Cherchi and Hensher, 2015; Kemperman, 2021). Tourists are often unfamiliar with a specific destination or tourist service, and therefore presenting them with more visual, virtual reality or interactive choice options might be of interest to better measure their preferences and choice behavior. Moreover, virtual or augmented reality environments also allow testing the effects of interventions on tourist preferences and behavior before they are actually implemented. This is an advantage, specifically when high investments are involved.

Moreover, technological innovations support the collection of more and more types of so-called big data and this data can be very useful in tourism research (Li, Xu, Tang, Wang, & Li, 2018). Big data sources for tourism research come in a variety of forms, such as user-generated data (e.g., tweets, online photos), device data (e.g., GPS data, mobile phone data), and transaction data (e.g., online booking data, customer cards). These types of smart big data sources might be used to understand how inner-city visitors’ activity choices emerge and evolve in space and time to provide city managers and planners with important information for future management and planning such as visitor flows and clusters, and interesting locations (e.g., Beritelli, Reinhold & Laesser, 2020).

Finally, to conclude, there is a challenge for more research and evidence to further expand knowledge on tourist choice behavior and support optimizing tourists’ experiences and quality of life.

Written by Astrid Kemperman, Eindhoven University of Technology, The Netherlands

References

Aksenov, P., Kemperman, A.D.A.M., & Arentze, T.A. (2014). Toward personalized and dynamic cultural routing: A three-level approach. Procedia Environmental Sciences, 22, 257-269.

Aksenov, P., Kemperman, A., & Arentze, T. (2016). A Personalised Recommender System for Tourists on City Trips: Concepts and Implementation. In De Pietro, G., Gallo, L., Howlett, R.J., Jain, L.C. (eds): Intelligent Interactive Multimedia Systems and Services 2016, Springer International Publishing Switzerland, 525-535.

Arentze, T., Kemperman, A. & Aksenov, P. (2018). Estimating a latent-class user model for travel recommender systems. Information Technology & Tourism, 19(1-4), 61-82.

Beritelli, P., Reinhold, S., & Laesser, C. (2020). Visitor flows, trajectories and corridors: Planning and designing places from the traveler’s point of view. Annals of Tourism Research, 82, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102936.

Buhalis, D. (1998). Strategic use of information technologies in the tourism industry. Tourism Management, 19(5), 409-421.

Cherchi, E., & Hensher, D. A. (2015).Workshop synthesis: Stated preference surveys and experimental design, an audit of the journey so far, and future research perspectives. Transportation Research Procedia, 11, 154–164.

Dellaert, B. G. C., Ettema, S. D. F., & Lindh, C. (1998). Multi-faceted tourist travel decisions: A constraint-based conceptual framework to describe tourists’ sequential choices of travel components. Tourism Management, 19, 313–320.

Gretzel, U. & Koo, C. (2021). Smart tourism cities: a duality of place where technology supports the convergence of touristic and residential experiences. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 26(4), 352-364.

Gretzel, U., Mitsche, N., Hwang, Y.H., & Fesenmaier D.R. (2004). Tell me who you are and I will tell you where to go: Use of travel personalities in destination recommendation systems. Information Technology & Tourism, 7, 3–12.

Grigolon A.B., Kemperman A.D.A.M., & Timmermans, H.J.P. (2012a). Exploring interdependencies in students’ vacation portfolios using association rules. European Journal of Tourism Research, 5(2), 93-105.

Grigolon A.B., Kemperman A.D.A.M., & Timmermans, H.J.P. (2012b). The influence of low-fare airlines on vacation choices of students: Results of a stated portfolio choice experiment. Tourism Management, 33, 1174-1184.

Grigolon A.B., Kemperman A.D.A.M., & Timmermans, H.J.P. (2012c). Student’s vacation travel: A reference dependent model of airline fares preferences. Journal of Air Transport Management, 18(1), 38-42.

Grigolon, A. (2013). Modeling Recreation Choices over the Family Lifecycle. Ph.D Thesis, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven.

Jeng, J.M. & Fesenmaier, D.R. (1998), Destination Compatibility in Multidestination Pleasure Travel. Tourism Analysis, 3, 77-87.

Kemperman A.D.A.M., & Timmermans, H.J.P. (2011). Children’s recreational physical activity. Leisure Sciences, 33(3), 183-204.

Kemperman A.D.A.M., Borgers A.W.J., & Timmermans, H.J.P. (2002a). A semi-parametric hazard model of activity timing and sequencing decisions during visits to theme parks using experimental design data. Tourism Analysis, 7, 1-13.

Kemperman A.D.A.M., Borgers A.W.J., & Timmermans, H.J.P. (2002b). Incorporating Variety-Seeking and Seasonality in Stated Preference Modeling of Leisure Trip Destination Choice: A Test of External Validity. Transportation Research Record, 1807, 67-76.

Kemperman A.D.A.M., Borgers A.W.J., & Timmermans, H.J.P. (2009). Tourist shopping behavior in a historic downtown area. Tourism Management, 30(2), 208-218.

Kemperman A.D.A.M., Borgers A.W.J., Oppewal H. & Timmermans, H.J.P. (2003). Predicting the duration of theme park visitors’ activities: An ordered logit model using conjoint choice data. Journal of Travel Research, 41(4), 375-384.

Kemperman A.D.A.M., Borgers A.W.J., Oppewal H., & Timmermans, H.J.P. (2000). Consumer Choice of Theme Parks: A Conjoint Choice Model of Seasonality Effects and Variety Seeking Behavior. Leisure Sciences, 22, 1-18.

Kemperman A.D.A.M., Joh C.H., & Timmermans, H.J.P. (2004). Comparing first-time and repeat visitors activity patterns. Tourism Analysis, 8(2-4), 159-164.

Kemperman, A. (2000). Temporal aspects of theme park choice behavior. Modeling variety seeking, seasonality and diversification to support theme park planning, Ph.D Thesis, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven.

Kemperman, A. (2021). A review of research into discrete choice experiments in tourism – Launching the Annals of Tourism Research curated collection on discrete choice experiments in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 87, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.103137.

Kemperman, A., Arentze, T., & Aksenov, P. (2019). Tourists’ City Trip Activity Program Planning: A Personalized Stated Choice Experiment. In Artal-Tur, A., Kozak, N., Kozak, M. (eds): Trends in Tourist Behavior: New Products and Experiences in Europe, Springer, Springer Nature Switzerland

Li, J., Xu, L., Tang, L., Wang, S., & Li, L. (2018). Big data in tourism research: A literature review. Tourism Management, 68, 301-323.

Randle, M., Kemperman, A., & Dolnicar S. (2019). Making cause-related corporate social responsibility (CSR) count in holiday accommodation choice. Tourism Management, 75, 66-77.

Ritchie, B.W., Kemperman, A., & Dolnicar, S. (2021). Which types of product attributes lead to aviation voluntary carbon offsetting among air passengers? Tourism Management, 85, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104276.

Rodríguez, B., Molina,J., Pérez, F., & Caballero, R. (2012). Interactive design of personalised tourism routes. Tourism Management, 33(4), 926-940.

Steen Jacobsen, J.K., & Munar, A.M. (2012). Tourist information search and destination choice in a digital age. Tourism Management Perspectives, 1(1), 39-47.

UNWTO (2021). COVID-19 response. Retrieved from https://www.unwto.org/tourism-covid-19

Woodside, A.G. & MacDonald, R. (1994), General System Framework of Customer Choice Processes of Tourism Services, in R. Gasser and K. Weiermair (eds.), Spoilt for Choice, Kultur Verlag, Austria.